Most people who go to Chichester on a regular basis know Tower Street as a place to park the car.

Now it is a place to enjoy history.

The final touches are being made to a £6.9 million project that will usher in a new era for the site of a former Roman bath house, which has been dated to the Flavian period, 69AD to 96AD.

Once housed in the Roman city of Noviomagus Reginorum, the site has since been used as a Saxon pottery, a bell-foundry, a wool-staplers, as medieval housing and a school, as well as housing the ultimate 20th-century item: cars.

The educational lineage will now merge with entertainment as The Novium museum opens its doors on Sunday, July 8.

With three floors and more than 2,000 objects, the aim is to tell the story of Chichester over the past 500,000 years.

All the objects are from Chichester District Museum’s collection of more than half a million items, which cover everything from geological artefacts to domestic items such as vacuum cleaners and mousetraps. These are stored at The Novium and the Collections Dis-covery Centre at Fishbourne Roman Palace.

Museum manager Tracey Clark says the collection begins with Boxgrove Man (his shin bone was found at Boxgrove in 1994 and was dated to 500,000 years ago) and runs through to the modern day.

“There has been a lot of interest in the Roman baths since they were excavated in the 1970s and that is what has triggered people’s fascination with this project.

“They certainly have the wow-factor, and the rest of the museum will keep visitors here.”

Evidence of the bath house first came in the 1960s with the discovery of part of a geometric patterned mosaic. Excavation started in 1974.

Archaeologists worked for more than a year to beat a development for a multi-storey car park on the site and unearth what was described as one of Chichester’s largest Roman public buildings.

A car park was built but it was a temporary structure. The council boxed over the remains and put sand over them to preserve them.

Clark says they have used a thematic approach at The Novium, which is “a new way of working in museums that fits in with the national curriculum for schools”.

“We are displaying objects in a completely new manner, linking objects that you might never put together.

“It should allow people to connect with the objects and themes, help them understand objects and how they have developed and how they changed people and the landscape.

“This is a contemporary approach to a museum, in a modern space, and 80% to 90% of the objects have never been on display before.”

To decide what they wanted to feature they began by identifying key subjects.

“We identified place and people as the most important overarching themes for the Chichester district.

“From that we broke out into what themes could come under those.

“We looked at our collection to see what the strongest represented themes were.

“So where we have used something for bravery – we might use that in a place theme.

“Rather than the emotion of wearing that piece of armour in the civil war, it might be what effect did the civil war have on Chichester.

“We no longer look at the object for who owned it and used it, it is more about the symbolic nature of the object and what it means to people themselves.”

The Novium replaces the Chichester District Museum, which dated back to 1831 and was most recently housed in an 18th-century disused corn store in Little London, Chichester.

“We outgrew the building. Our collection was too big and it didn’t offer us the opportunity to display it at its best.

“This building has allowed us to put a great many more objects out on display and make it more accessible for the public.”

The Romans

Resident Roman expert Anooshka Rawden, the collections officer and museum assistant manager, says The Novium is authoritative not authoritarian.

“We are presenting facts but it is more about asking questions.”

A few minutes stood in front of the Roman bath house with her and most of mine are answered.

“Imagine it like a golf club or leisure centre,” she explains.

“People would go for leisure reasons, to spoil themselves, for health reasons, but also to make business deals – it was a place they could discuss business informally.

“It stems from the idea of Cultus: the maintenance of the body, with regular plucking, shaving, massage. It was the same then as it is now.”

Indeed, many of the bath houses were rife with scandal, and ironically their eventual decline came about thanks to price-fixing and debasement.

With Roman bath houses came new ideas such as running water, heated floors and walls, and the ventilation system.

Stand in front of the bath house and the fundamentals of architecture are before you. Fittingly, the systems are repeated throughout The Novium.

The Romans were in Britain between 43AD and 410AD, and Rawden explains the Chilgrove Mosaic (pictured opposite) would probably have been created by travelling building gangs.

“They were technicians not artists. The theory is that they had pattern books and choosing a mosaic would be a bit like picking carpets for a dining room.”

Such finds are normally left in situ for preservation. But, as Rawden explains, after 2,000 years there has been some plough damage by unwitting farmers and because it was probably done by Roman cowboy tradesmen, it needed to be moved.

“They did a good job on the design but laid it badly. They were Roman builders so probably good at covering up their mistakes.”

Like the Italians today, the Romans were good at selling their culture.

They were business-minded, artistic, masculine, domineering.

Rawden thinks that the Romans probably saw the indigenous British population as barbarians, who would have been fascinated by their multiculturalism.

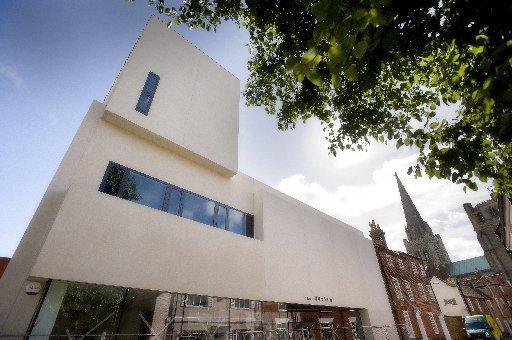

The Building

The 1,300sqm museum and 26 apartment residential block is situated in Chichester’s northwest quadrant.

At the end of Tower Street is Chichester cathedral and architect Keith Williams was keen to pay homage to the 900-year-old edifice.

Views from the museum’s second floor gallery, at the top of a bright staircase flooded with natural light, take in the city’s rooftops, the cathedral spire and its bell tower.

“It’s a reward for getting to the top,” says Williams, whose previous projects include designs for The Marlowe Theatre in Canterbury, Athlone Art Gallery in Ireland, and Centro Culturale di Torino in Italy.

“We see it as a transition space that lifts the spirits. Through the cathedral window one can look out across the old city from a place with an eye to the future.”

Though Gallery Two, on the second floor, is the Woodstaplers Room for use by study groups. There are more grand views from there.

“We’ve opened up a new way of looking at the city,” he says.

From the outside, the museum is clad in pale reconstructed golden stone similar in tone to the cathedral and the Market Cross.

At ground level a modern glass foyer meets the street.

Inside, the design opens out into a vast entrance gallery with a viewing platform and glass vitrines built around the museum’s centrepiece: the Roman bath house dating back to the first century AD, discovered in the 1970s.

“Here we used modern pouring concrete with a slight sheen to make it easy to identify the old and the new.”

The building is functional: the staircase up to the first floor is built above the old baths to give space for audio-visual projections.

Building over archaeological remains was a first for Williams, but few architects will have worked to such a brief.

Because the council had already selected the site for a museum, the technical challenge was to make it work in a way that meant the artefacts were centre-stage.

“To meet the challenge we built the museum on piles rather than foundations,” he explains.

“It will protect the archaeology.”

He says light for an architect is like melody for a musician. And by mirroring similar forms the Romans pioneered 2,000 years earlier, above the stairs are ceiling windows that bring natural light and act as ventilation to regulate the museum’s temperature.

Williams wanted to mark the point where the old city, from the Roman epoch through to medieval times, finishes and the 20th-century developments begin.

“I wanted to create a bridge between the historic and new buildings,” he says.

How is it funded?

The Novium cost £6.9 million. According to museum manager Tracey Clark, the six-year-old project has been funded through capital funds, “which can only be spent on enhancing or creating buildings and facilities and not on day-to-day running costs of services”.

The council is selling the residential development next to The Novium, and the old museum building in Little London, to offset the costs.

Entry fees will provide regular income.

The Objects

On the ground floor are the largest objects in the collection. The bath house is the big draw for history buffs and archaeologists as well as those interested in the pioneering Romans.

An audio-visual guide to a place which would have been a meeting place for chatter about business deals, relaxation and pampering is projected onto the spandrel of the stairs up to the first floor.

Also on the ground floor is the Chilgrove Mosaic, which dates back to the fourth century and was discovered at Chilgrove Roman Villa. The Jupiter Stone, found during excavations in West Street, Chichester, in 1934, is a portion of a Roman sculpture base dated between the late first century and early third century AD, dedicated to the God, Jupiter.

The first floor hosts the Time And Place Gallery.

An anteroom pinpoints important locations of historical importance and a curiosities case contains an underwater hedgehog and an elephant’s tusk found in a lobster pot in Selsey dating to the Pleistocene age, between two million and 11,000 years ago.

Inside there are items to sniff and touch – for a sensory experience – such as cocoa and Bovril as part of “domestic places”. A giant glass cube in the centre of the room contains a municipal moon lantern dating to 1600 and a Jackson Cooker from 1945.

An eerie child’s coffin pillow is part of the “burial places” selection.

A Toll Board on the wall is from 1875 and the former Butter Market. It was discovered in an ironmongers store in 1990 and lists unusual items.

“It shows what the area could provide for people,” says Jennifer Bowser, exhibitions officer.

“The glass cube is also important because it will allow us to take on loans from national museums and travelling exhibitions.”

Upstairs the focus is people and emotions.

The most cumbersome object – a jail door from Eastgate Gaol, demolished in 1783 – is not the most frightening.

Some portable stocks, made for Chichester Corporation in 1828 (dated thanks to an article in the Brighton Herald), were used to punish drunk and disorderly behaviour.

There are collections themed around bravery, sorrow, joy, creativity and beauty.

“Items that were supposed to make us more beautiful often did us more damage,” jokes museum manager Tracey Clark.

“We look at the ugliness of beauty. There are curling irons that look lethal.”

Even the Romans were avid preeners – shaving and plucking and waxing – and an antiquated make-up bag is proof.

“Visitors are supposed to have emotional response, to relate the objects to their own lives,” adds Clarke.

Try on a Roman Centurion helmet and, who knows, you might feel invincible.

* The Novium is in Tower Street, Chichester, and opens on Sunday, July 8.

* Opening times:

April to October: Monday to Saturday, 10am to 5pm; Sundays and bank holidays, 10am to 4pm.

November to March: Wednesday to Saturday, 10am to 5pm; Sunday, 10am to 4pm. Last admission is half an hour before closing time.

* Prices:

Adults £7, £6 concessions, child (aged four to 15) £2.50, children aged three and under, free. Family (two adults, two children) £16.50. Adult groups (four or more adults) £6.50 each.

* For more information, visit www.chichester.gov.uk/thenovium

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here