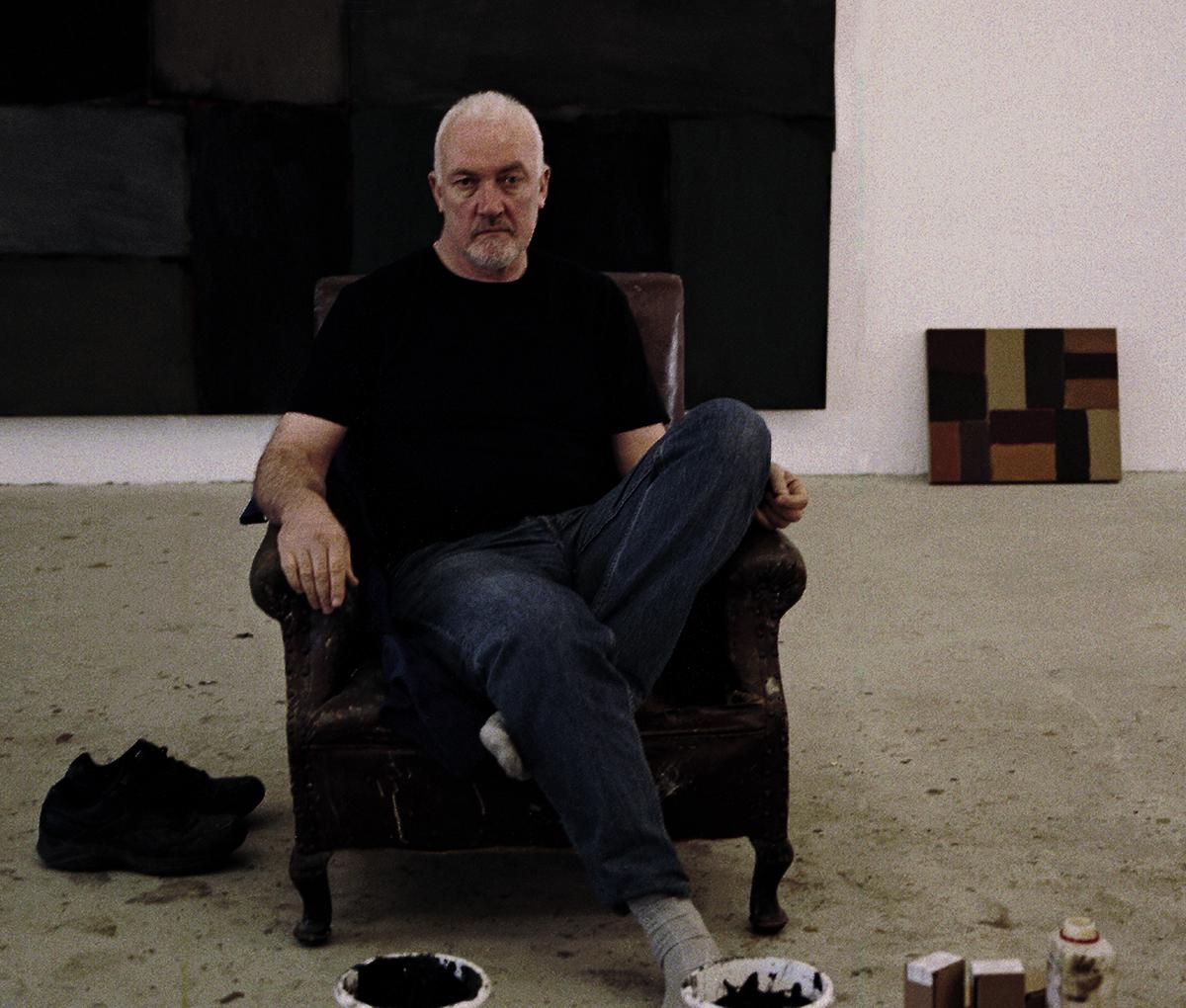

Twice Turner Prize-nominated artist Sean Scully is lying on the sofa in his New York house on the banks of the Hudson River.

He’s been playing on his young son’s trampoline and done his back in.

“I bought my kid a trampoline and foolishly jumped up and down on it for days,” explains the adventurous 68-year-old.

“My back is terribly messed up. It’s a beautiful trampoline and I thought it was going to be great, but then someone said it’s not for adults because you are compressing your spine... and I’ve got a slightly out disc. Plus I had major back surgery not that long ago.”

The Dublin-born, London-raised, naturalised American, who has lived in the States since 1975, talks slowly, philosophically, in an accent more Michael Caine than Michael Douglas.

His precision is disarming, especially when something unexpected comes along.

He ends up sounding as if he’s a character from Spinal Tap rather than a revered, pioneering figure from the contemporary art world, whose striking abstract works – often drawing comparisons to Mark Rothko and Piet Mondrian – command huge sums.

“I’ve always done stupid things like this with my body,” he adds, before explaining his planned visit to Chichester to talk about his show of triptychs opening at the city’s Pallant House Gallery tomorrow might have to be put back a few weeks.

Sounding decadent, reclining on his lounger, he slips into our conversation that he’s never slid down the original Ghostbusters fire pole at his grand riverside home.

“I bought this beautiful house, which was built by [actor] Bill Murray, a year ago. He was making gazillions at the time and got the fire pole installed from an upstairs guest apartment room to the garage.

“It’s true. If you want to get there quickly, you can use the fire pole instead of the stairs. My son loves it.”

Scully Senior has a thing for celebrity homes, having also rented Madonna’s old house in London.

But his next step is to buy a boat and sail up the Hudson River, “which I hope is not going to be followed by drowning”.

He loves the Hudson River School painters, such as John Frederick Kensett, Albert Bierstadt, Frederic Edwin Church, and has embraced America, as the country has embraced him.

He sees parallels between himself and Lucian Freud, another painter twice nominated for the UK’s most prestigious art award, once in the same year as Scully.

“What’s really interesting to me is he was England’s greatest artist. But Lucian Freud, who is a great painter, was embraced by the Americans and that is what made him huge.”

Scully cites his stand at a recent Frieze Masters art fair, the fact he has had more than 130 museum exhibitions and is never without a show somewhere in the world, as evidence that he is in the big league. “I used to be a cheeky young guy, now I’m a master.”

His work can be seen in permanent collections at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, the Guggenheim Museum and the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis.

He has honorary degrees from top institutions and has taught at Princeton University and the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Munich. His former students include perhaps the most famous artist in the world: Ai Weiwei.

Speaking about Freud, he says, “Our positions are quite similar – obviously generationally different but there is a great stubbornness about it, as with a lot of great painting. My work is very obdurate. It keeps coming.”

Scully says he never runs out of ideas.

“I have too many. I’m trying to get rid of them so I can concentrate on the few things I am doing.”

Right now he is doing Duric paintings, some other looser paintings on aluminium and continuing his Wall Of Light paintings, dealing with colour.

He compares painting to unfolding and folding a blanket.

“Every time you fold it over, it shows another side. And every time you unfold it, you’ve opened it up again, then you fold it up again and it shows another side, another possibility.”

Which, for Scully – running contrary to many artists’ ideas that painting as a medium has come to a dead end – makes it endless.

“I’m not interested in those remarks. It’s a bit like saying kissing has come to a dead end.

“People said that about 50 years ago and painting is flourishing in other parts of the world. Certainly it is flourishing in Germany, the capital of painting, and in China.”

But we are in an age of new media.

“The thing about painting is it can do something other things can’t. It’s so primitive, so basic, that you can never get over that.

“Anything else you do needs props. It has to be plugged in or assembled, whereas a painting is a concentrated image that can be moved around and put up anywhere.”

Scully has studios in Barcelona and Munich, as well as New York. He thinks internationally.

“I have led the life of a traveller. I have enjoyed that life and I believe in that.”

After his show in Chichester, he will take an exhibition of his work to Shanghai.

“Art is a force for good – that is its job. And it is its job to represent the strangeness and possibility of human nature. I love the influence of art in China: it is transforming that culture in the way rock and roll transformed Russia and West and East Germany in the 1960s.”

He says China – “an older, more refined culture” – is finding its way back to beauty.

“Beauty is something transformative.

As Sigmund Freud said, ‘Nobody really knows what it is but human beings can’t live without it’.

“As soon as China got to a certain point of confidence economically, art started to be talked about.

“The idea of beauty and imagination, invention, strangeness, harmony and disharmony started to be discussed, because you can’t just have a mechanical world.

“Human beings are not like that and now there is a movement that has taken place that the government in China is no longer able to turn back any more than you can turn back the sea.”

Scully wants his work to make people feel affirmed about themselves.

“I don’t want them to have an experience of that’s a fantastic painting then leave. I want the painting to affirm them, so that it is a more useful and long-term relationship.”

But his work – distinctive for an abstract artist because it is philosophical rather than theoretical – has never really taken hold in England.

“As a friend of mine once said, England was the only country in Europe which did not convert to abstraction. And because of that, and because of the history of the culture, the massive influence of Shakespeare, verbal art, the theatre and so forth, that kind of abstract thinking, free-wheeling structural thinking, has not taken root.

“So there is always going to be greater emphasis on sculpture, figurative painting and realism than there is on abstract thinking.

“I’m more interested in the latter because that is more connected to the future.”

Still, when he studied at Croydon College of Art and Newcastle University in the 1960s, he loved John Hoyland, Paul Huxley and Ian Stephenson. “They were moral examples more than direct pictorial influences because I was quite a curious student and pretty inventive.”

Then there was William Scott Painter, as well as German expressionism, before someone gave him a Rothko catalogue, which confirmed his interest in abstraction.

Dark Pink Triptych (2011), recently acquired by Pallant House, was the catalyst for the show.

It will be hung alongside drawings, etchings, minimal works from 1975 to 1980 and other triptychs he did recently in the German countryside, such as Arles Arben Vincent, which takes its name from the French town the Dutch master loved, and is the same painting done three times with different colours.

“What’s interesting about the number three is that it’s the first number that implies infinity.

“Simultaneously, you can use it as structure to make one panel central or more important than other panels, because it is in the middle. It has multiple cultural uses and references.”

It’s been mostly used in sacred paintings, but Scully passed through minimalism and is interested in “seriality”, the idea of things going on and on and on.

“I find the number three very interesting because Jean-Paul Sartre’s description of hell in his play No Exit features three people. You never get resolution. It just keeps tumbling. It’s an argument towards infinity.

“In a painting about three, it never settles down, and that’s what I like – things that are difficult to make static. That structure is very fertile because it can mean harmony or hell culturally.”

He says the birth of his son Oisín in 2009, to his wife, painter Liliane Tomasko, who he married in 2007, rejuvenated his practice. But it has not levelled him out.

“I feel mixed up. I’m like the tramp in Lady And The Tramp. Of course the tramp ends up living the domestic life though.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here