Personal stories from the First World War

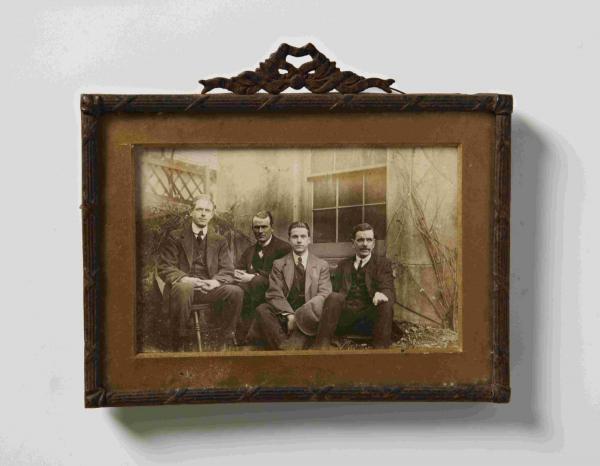

Drawing from letters, diaries, and personal items War Stories tells the tales of 16 Brightonians and the roles they played both in the trenches and on the home front.

Programme co–ordinator for Brighton Museum and Art Gallery’s exhibitions, Jody East, says the focus on individual stories was a way of making it real for people 100 years on.

“Everything to do with the First World War is huge – the numbers of countries involved, the people, the politics, it’s staggeringly overwhelming,” she says.

“Focusing on individuals who lived at that time makes it more engaging than a history lesson on the political reasons behind the war.”

An appeal went out across the city for stories and family objects from the conflict – something harder to find with the passage of time.

“Now people are much more aware of their family histories – which is very different from ten to 20 years ago,” says East. “With the Second World War people still have a lot more in their family collections, the First World War is a little harder to find things.”

One aspect which came across in the research was the disconnection between the home front and the war taking place across the English Channel.

“During the Second World War everyone at home was affected by the bombings and The Blitz,” says East.

“It is much harder to understand how life in Brighton carried on almost as normal, even though the First World War was only a few miles away in France. Brighton was a holiday resort and remained a holiday resort.”

That said the war still had a massive effect on society.

“Every family that sent someone off to fight was affected,” she says. “Conscientious objectors’ lives were completely changed – a lot were sent to prison and their families had to deal with that.”

Beginning with Eileen Daffern, who was born on January 1 1914, the exhibition takes a chronological look at tales from the war, encompassing Belgian refugees, Brightonians serving on the frontline, and the experiences of wartime nurse Florence Holdgate who served at the Kitchener Indian Hospital in Brighton before being shipped to the Middle East.

There are more unusual stories too, such as Albion goalkeeper Robert Whiting who joined the 17th Service Battalion Football Middlesex Regiment after mounting criticism when the football leagues began again in August 1914.

And there are items from conscientious objector Arthur Maxwell Saunders who spent part of the First World War in Wormwood Scrubs for refusing to join the armed forces or take up a non–combatant role.

The love affair between nurse Betty Donnelly and seriously wounded sergeant major George Edward Victor Fulkes links into the seafront display Dr Brighton’s War (see opposite) exploring the hospital city Brighton became.

And the exhibition also has personal letters and charity items from Ellen Thomas–Stanford of Preston Manor. Since April the Preston Drove manor house has been telling the story of Ellen’s grandson Vere Benett–Stanford in Steeplechasing Shell Holes: A Young Man’s War. The heir to the manor served with the Royal Field Artillery during the war in France.

“We have tried to keep the stories very contained,” says East. “We decided not to provide so much contextural information. It makes each story more powerful if people are looking at and reading objects related directly to that person.”

The exhibition also features a resource area with many of the other stories collected during the museum’s research.

“We weren’t going to restrict ourselves to Brighton and Sussex,” says East. “But so many strong stories came through we were able to narrow it down.”

The voices in the exhibition will be brought to life on Saturday, July 19, and Thursday, August 21, between 2pm and 4pm, with readings from a selection of letters and interviews connected to the exhibition.

And members of the Brighton Youth Theatre have been filmed doing readings, which will be screened during the run.

“We have tried to use the voice of the people we are focusing on as much as possible,” says East.

“When [soldier] Vernon Evershed’s parents write to him on his 21st birthday they are both wishing they were there with him. His father wants to shake him by the hand.

“The language they use is not that different from how families speak to each other now.”

The Royal Pavilion as an Indian hospital

The Royal Pavilion’s role as an Indian hospital during the First World War is well-documented.

But a new exhibition on the seafront will show Brighton played a much wider part as a hospital city.

Within nine days of war being declared current sixth form college BHASVIC was turned into the Second Eastern General Hospital – the first in the country to be set up to receive troops from the battlefield.

Collections projects curator Andy Maxted has been researching Brighton’s role in helping troops convalesce for this temporary seafront display, which is expected to be seen by up to 100,000 visitors a day.

“With Brighton just up the coast from Southampton and the southern and eastern ports it ticked many boxes,” he says.

“Not only was it a healthy environment in which to recover, but it was also well set–up to entertain the troops and distance them from the experiences they had been through.”

Brighton never really closed down during the First World War.

“People still came down from London for holidays,” says Maxted. “The theatres and cinemas were still open.

“During the First World War a lot of coastal towns were bombed by Germany, but Brighton never was. If it wasn’t for the injured troops around you wouldn’t have been reminded there was a war on.”

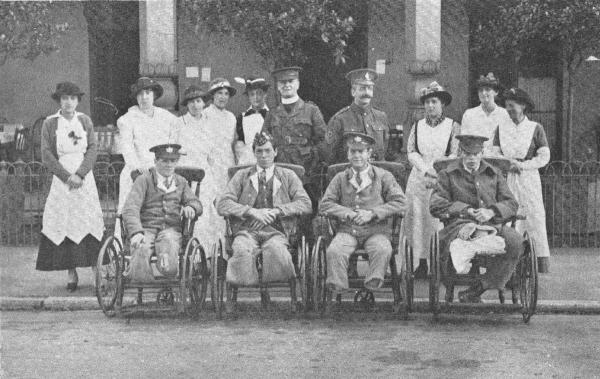

Brighton was receiving thousands of injured troops – who gave up their regular army uniform for the hospital blue seen around the city.

Among the items on display are postcards from the soldiers telling their families where they were, and images from the various hospitals set up around the city after the conversion of BHASVIC.

Maxted highlights how more schools were converted in Manor Road and Stanford Road in Brighton and Portland Road and Holland Road in Hove, as well as buildings in Lewes Crescent and Palmeira Square adding to Brighton’s grand total of 23 territorial hospitals.

In addition there were 14 auxiliary hospitals across the city, which acted as convalescent homes staffed by the Red Cross rather than the military.

The Royal Pavilion initially housed Indian soldiers – as legend has it to remind them of home.

But after 1916 the pavilion looked after limbless soldiers, who remained there for treatment and rehabilitation until August 1920.

“About 6,500 amputees went through the Pavilion Military Hospital in those four years,” says Maxted, pointing out a total of 41,500 British troops suffered amputations as a result of the war.

“The quantity of seriously injured men is massive. A whole infrastructure grew throughout the period of the war.”

To help the amputees reintegrate into society a diamond polishing factory was opened in Brighton, on the site of the Yellow Storage Company off Lewes Road, employing 2,000 seriously injured amputees.

“At the beginning of the war a soldier might die from a serious leg break,” says Maxted. “As the war went on medicine improved so much people could recover from terrible injuries.

“Brighton was well–known for its health and leisure so it was an ideal place to help troops convalesce.

“Hopefully the display will help people understand Brighton wasn’t just any other city during the First World War.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here