Seventy-five years since the end of the Spanish Civil War, Picasso’s Guernica remains most people’s lasting image of the three-year conflict.

If it is not Picasso’s masterpiece – made in Paris but returned to Spain after General Franco’s death in 1975 – it is Ernest Hemingway and George Orwell’s writing, which evoke a forgotten war described by Stephen Spender as the “poets’ war”.

But British artists – like the British people – offered their own response.

Pallant House Gallery’s autumn show, Conscience And Conflict – British Artists And the Spanish Civil War, is the first exhibition to explore British artistic reaction to the war fought between Franco’s Nationalists and the Spanish Republicans from 1936 to 1939.

Britain’s response

Gallery co-director Simon Martin says British artists responded because they felt they had to do something with the rise of not just Franco but also because British fascist Oswald Mosley and his Italian and German fascist counterparts – Mussolini and Hitler – were gaining traction.

“You see work produced by British artists at the time and they were responding to the issue,” he says, speaking at a recent press launch for the show.

“It was a question of conscience – whether they supported the democratically elected Republicans or the Nationalists and their fascist allies.

“For a lot of them there was almost this sense of foreboding if they didn’t do something in Spain something similar would happen in Britain.”

Many artists responded by forming the Artists International Association (AIA), which at one point had 600 members. These ranged from titans of British modernism such as Augustus John and Stanley Spencer to little-known artists, designers and schoolteachers. The AIA organised fundraising exhibitions including Artists Help Spain in 1936, which raised funds for an ambulance, and Portraits For Spain in 1938, for which Eric Ravilious painted a country house.

“The debates at the time between artists were how could you engage with what was going on in Spain and could you be an abstract artist and be engaged? A lot of work in the first room of the show is figurative and didactic but manages to carry a message”.

Frank Brangwyn

Many of the left-wing avant garde decided to produce posters to raise money for campaigns for medical aid and food to send to Spain. Ditchling artist Frank Brangwyn made a poster called Spain which looks like a renaissance painting with a Madonna-like mother holding children with burning buildings in the background. As part of his research for the show and accompanying book, Martin found a photo of Brangwyn in his studio alongside the poster.

“He is Catholic and of course one of the issues in the Spanish Civil War was this anti-Catholic feeling among the Republicans – so here is this Catholic doing a poster for aid for the displaced. It’s an extraordinary scene and work,” he says.

Henry Moore

Yorkshire-born sculptor Henry Moore, who would later create the memorable London Underground sketches during the Second World War, made lithographs and sculptures to raise money for the 500,000 refugees in internment camps in France. The art historian David Sylvester pointed out how the sharp pins of Three Points (1939 – 1940) reflect the “screaming mouths and dagger-like tongues” in studies by Picasso for Guernica.

Writing at the time, Moore put his anguish to words as well as sculpture, “unless he is prepared to see all thought pressed into one reactionary mould by tyrannical dictatorships – to see the beginning of another set of dark ages – the artist is left with no choice but to help in the fight for the real establishment of democracy against the menace of dictatorships”.

Ursula McCannell

Child prodigy Ursula McCannell’s Family Of Beggars depicts Spanish refugees in France. McCannell visited Spain in 1936 when she was 13 and painted a series of paintings in the style of El Greco and Picasso’s Blue period based on articles and reportage by photojournalist Robert Capa. A review in the Daily Mail at the time said, “She seems to typify all suffering in Spain”.

“They are wonderful and you wouldn’t believe she is so young,” says Martin.

Edith Tudor-Hart

Four thousand Basque refugees came to England aboard the steam ship Habaña in May 1937 following the bombing of Guernica. Many ended up in hostels in Worthing, Hove and Brighton. Photos in the exhibition by Edith Tudor-Hart show the main refugee camp in North Stoneham in Hampshire with Basque children playing cricket with British schoolchildren.

More than 2,500 British citizens went to fight for the Republicans as part of the International Brigade (IB). And a few of these recruits were artists.

Clive Branson

Clive Branson, a distant cousin of Richard Branson, joined the IB and made drawings of other volunteers. He was from a wealthy family and went to the Slade School Of Art, but in the 1930s became a communist. He married Noreen, the fifth Marquess of Sligo's granddaughter, who gave her dowry to the poor people of Battersea and then spent her days selling the organ of the British left, the Daily Worker. Branson’s painting Noreen And Rosa (1940) emulates the naïve style of the untrained Ashington miners – recently celebrated in the stage show The Pitmen Painters – to create a working class style of painting. Noreen reads one of the Left Book Club’s prints on Spain.

“It just illustrates how ordinary and middle-class people engaged with the issues,” says Martin.

“The idea was people would read critical books and understand the issues of the day.

“The Left Book Club had these distinctive orange covers and by 1939 had more than 57,000 members. It gives you an idea of how many people were engaged.”

Branson was captured in Calaceite in March 1938 and imprisoned by the Nationalists. He wrote poetry and sketched inmates in the San Pedro de Cardeña camp. A series of paintings made on his return feature in the show’s final room and include Inside The Prison Camp In Spain – Viñalta.

Felicia Browne

The first British person to be killed in the war was an artist: Felicia Browne. She had gone to Barcelona for the People’s Olympiad, a rival games organised by the left-wing coalition, Popular Front, in response to the Nazi-organised 1936 Berlin Olympics. When the People’s Olympiad was abandoned due to the outbreak of civil war, she ended up joining a communist militia before the Republicans coalesced. She wanted to become a machine gunner but in the end became a stretcher bearer. She was shot dead on duty.

“She chose direct action as opposed to art,” explains Martin.

“She was killed in 1936 and that would have been that but they found her drawings in her sketch books in her bag and they were taken back to England. The AIA decided to hold an exhibition and she became a heroine for the art world. You can see from her drawings of Spanish peasant women and her self-portrait she had a distinctive style.”

The London exhibition raised a huge amount of interest about what artists should do to take part and the Bloomsbury artist who lived at Charleston, Duncan Grant, wrote the exhbition's catalogue essay.

Not only was the Spanish Civil War the first conflict where instant images and films showing action were available to the British public, it was also the first time women fought in war.

It was an internal conflict with a huge international element too. Ernest Hemingway called the Spanish Civil War “the dress rehearsal for the inevitable European war” – and it’s impossible to disagree with the American writer whose experiences covering the war were the basis of his masterpiece For Whom The Bell Tolls.

When the British government turned its back as fascist dictator Genreal Franco unleashed a Nationalist assault on the Spanish people it allowed Hitler and his army to flourish. Because of the British government’s policy of appeasement, Hitler’s Condor Legion got away with bombing the Basque village of Guernica on behalf of General Franco. The annihilation was the first time civilians had been targeted in a war in Europe.

Though the British government stood firm on the Non-Intervention Agreement it had signed with 24 other countries, and refused to arm the Spanish Republicans part of a Franco-British pact, the British people responded strongly.

“That had a profound impact on the Bloomsbury group in terms of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell and all of them became involved in organising events,” says Martin.

Picasso in Britain

Sussex-based artist Roland Penrose persuaded Pablo Picasso to allow his response to Guernica to come to Britain. It visited the New Burlington Galleries in London in 1938 and a few months later the Whitechapel Art Gallery in the East End and a car showroom in Manchester where a huge number of workers saw it.

Vanessa Bell and her son Quentin visited Picasso in his studio in Paris while he was painting Guernica and persuaded him to donate a drawing to be auctioned at the Royal Albert Hall at a fundraising event in June 1937. Picasso’s artistic response, which was sold in aid of the Basque children, is now in the Tate collection.

“Picasso is not a modern British artist but he is central to the story of British artists and the Spanish Civil War,” says Martin. “When the Basque city was bombed in April 1937 it was a turning point of public opinion.”

Although the Nationalists immediately put out propaganda blaming the Republicans for the atrocity – journalists including Times reporter George Steer were on the ground and saw Hitler’s planes flying overhead.

Picasso, enraged by this, shocked and in mourning by the massacre of innocent Spanish people, painted furiously. He made 27 drawings and nine paintings on the subject.

“The significant thing is it was not a military target,” says Martin. “They went on market day and strafed civilians. It was horrific. Picasso painted Guernica over the following weeks to be exhibited at the Paris International Exhibition.”

Pallant House does not have Guernica but a group of artists have remade the picture as a banner for its Garden Gallery.

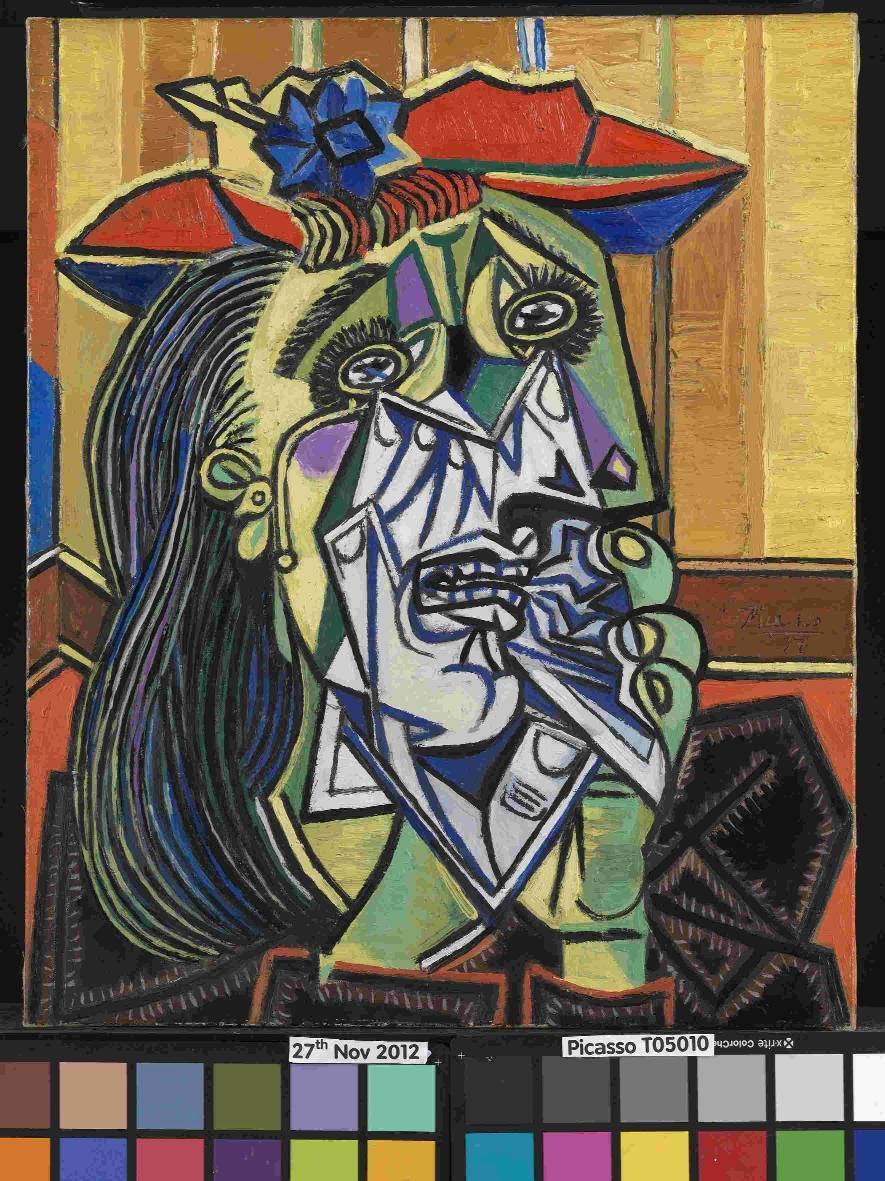

One major coup it does have is Weeping Woman on loan from the Tate. It is Britain’s most iconic Picasso painting on the theme. He created a series of works using the motif and the version at Pallant House was bought directly from the artist by Roland Penrose.

It joined Guernica on tour when Picasso brought it to England and a photo of its presentation at New Burlington Galleries shows the future leader of the Labour Party, Clement Attlee, who had a battalion of IB named after him, standing in front of it. He is giving a speech with Penrose and others sitting on the stage.

“It was often said abstract art could not be understood by working class people and the artists of the day repeatedly said yes it can,” says Martin. “When it was shown at the Whitechapel as many as 14,000 went. They were mostly working class people and the price of admission was a pair of boots to be sent to Spain. They did all kinds of talks and everybody got the potent message of the work.”

A Weeping Woman print, often described as one of the most important etchings of the 20th century, is another work bought by Roland Penrose at the same time as he bought the Weeping Woman painting and the two comic-book style works in The Dream And Lie Of Franco, of which a thousand copies were printed.

Artists acquired the series of prints to support the Spanish Republic. Henry Moore had a copy in his Perry Green house.

Hastings-born critic John Golding wrote “more than any other work by Picasso, The Dream And Lie Of Franco breaks down, as the Surrealists so passionately longed to, distinctions between thought, writing and visual imagery.”

Martin agrees. “What artists learned from Picasso is you could create a stronger emotion through abstraction and FE McWilliam’s Spanish Head (1938 – 1939) and Merlyn Evans’ Distressed Area (1938) are fine examples.”

In the same room in the exhibition Walter Nessler’s Premonition (1937) and John Armstrong’s Revelations (1938) show how the bombing directly affected British artists.

Quentin Bell

Sussex artist Vanessa Bell’s sons were particularly moved. Quentin painted May Day Procession With Banners in July 1937 and, despite Vanessa’s protestations, Julian went to Spain to volunteer as an ambulance driver.

Julian had previously been a pacifist and even edited an anthology of conscientious objectors from the First World War. But with the rise of fascism he felt he had to travel to Spain to help the Republicans.

Vanessa wrote to Julian before he left and mentioned Felicia Brown’s tragic death. She wrote how it was better for an artist to stay in England to change public opinion and raise funds rather than become cannon fodder. Just days after Quentin had painted May Day Procession, Julian Bell was killed, aged 29, after a Nationalist bomb attack in the Battle Of Brunete.

“The artists were incredibly politically motivated in a way we have not seen in British art since,” says Martin. “That’s undoubtedly because of extraordinary times in which they were living.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article