Julian Germain: The Future Is Ours

Towner Art Gallery, Devonshire Park, College Road, Eastbourne, Saturday, October 10, to Sunday, January 10

MOST schoolchildren remember the day the photographer came to school – partly because the experience feels so alien.

Usually the whole class is smartened up, taken to the school hall or gym, arranged by height order around their teacher on chairs and benches and then told to smile for the camera.

With his series of classroom portraits UK photographer Julian Germain was keen to avoid this artificial set-up and instead capture some of the atmosphere of the classroom.

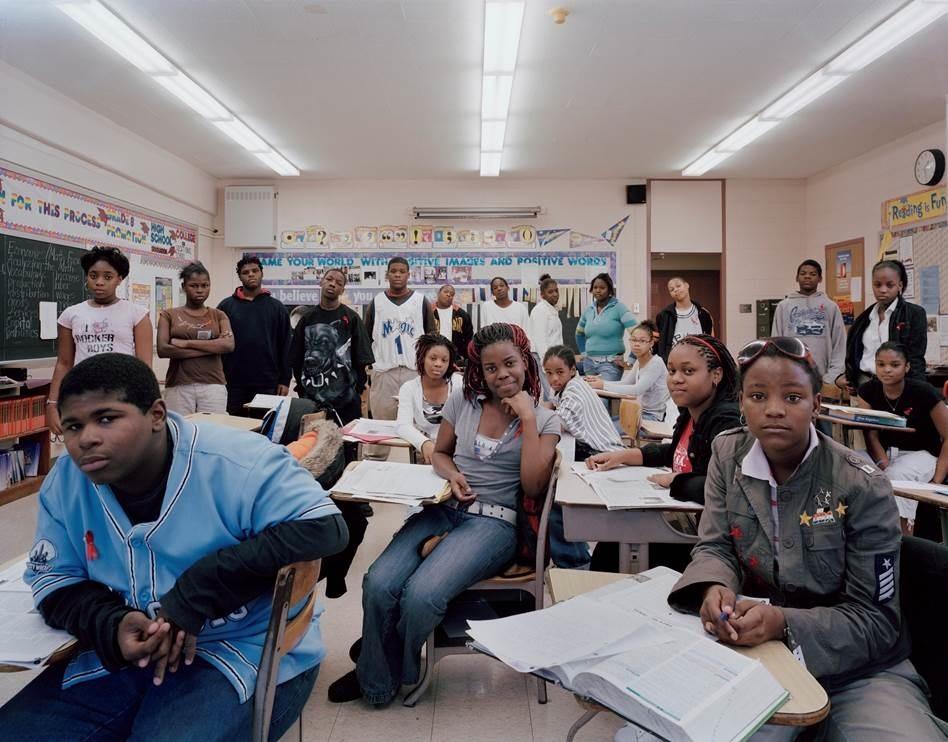

Taken over the course of 11 years his images still feature every face in the class, but not necessarily in the same scrubbed up forced way.

“If they say ‘Do you want me to smile?’ I tell them to do what they want,” says Germain, fresh from a damp outdoor filming session with a group of Year Four children at a beekeeper’s hives.

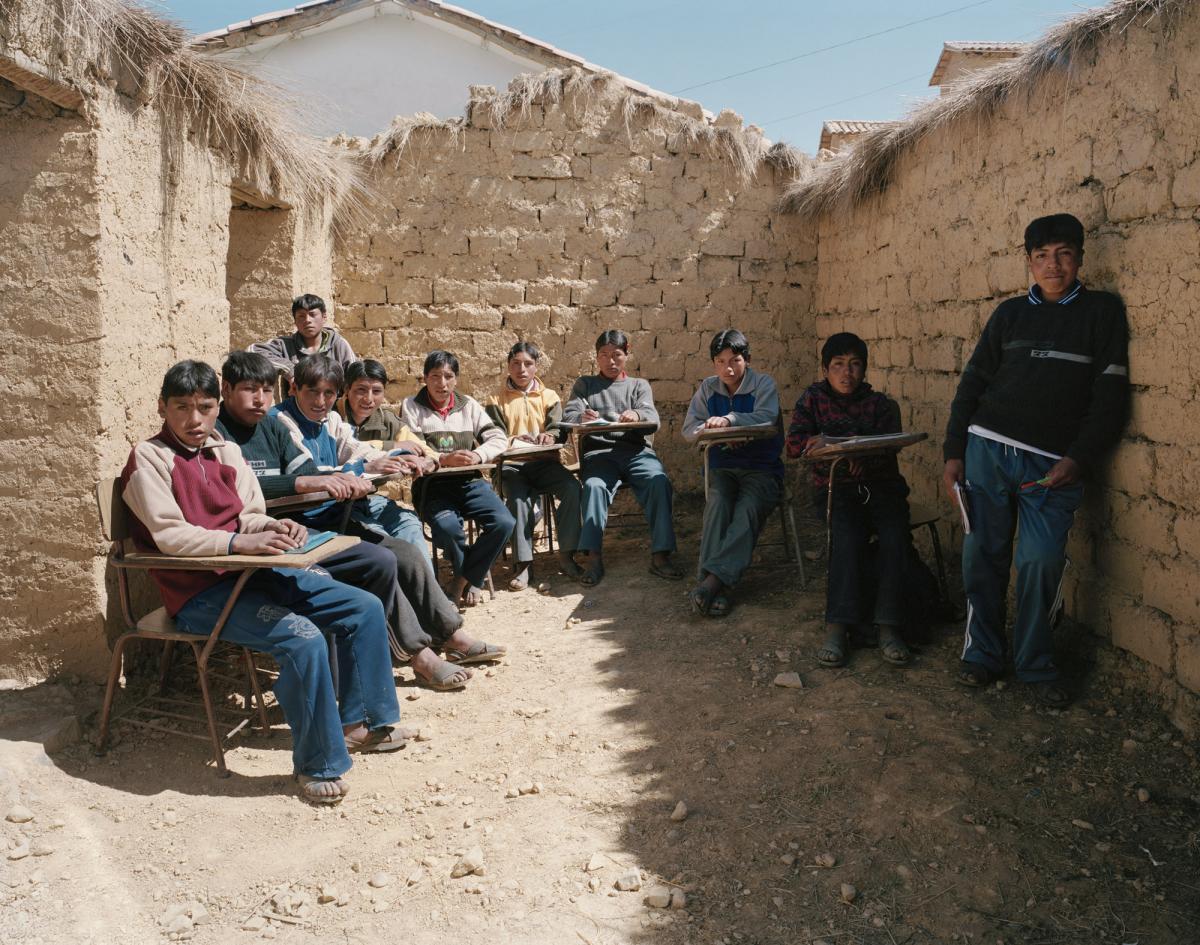

“I liked the idea of the class portrait as a starting point, but I wanted to develop a way of working to look at the environment they learn in.

“I was driven by the feeling I had for a long time that for people from an underprivileged background education is crucial. I wanted to explore what a country offers kids in terms of education.”

His work takes in classrooms across the world, from Tokyo and Brazil to Bradford, as well as a recent set of shots from Eastbourne’s Cavendish School in Eldon Road, Bishop Bell School in Priory Road, Motcombe Community School in MacMillan Drive and West Rise Junior School in July and September.

He deliberately ensures the images make no judgements or political points.

“I do think the work is ultimately about us adults facing up to our responsibilities towards children,” he says. “It’s adults who create the world that children grow up into – it’s about a belief in society, and our responsibility to all kids and each other.

“With portrait after portrait you’re faced with hundreds of kids looking at you with an intensity which I hope is quite challenging and makes you think about that responsibility.”

The project arose in 2004 after Germain was asked if he would like to work in schools in the north east of England.

“I had been interested in doing something about schools for years,” he says.

“When somebody gave me the opportunity I surprised them by saying I wanted to make a piece of work about the school, rather than just go in and do projects with the kids about nature or the environment.”

He developed a style of taking the shots, using long exposures of between a quarter and half a second to allow both the foreground and background to be in focus, avoiding large amounts of flash.

He says the act of arranging the lights and setting up the shot helped his subjects realise it was something to be taken seriously – although it did mean he found it hard to work with extremely young children not used to sitting still for any length of time.

“The guidance I gave the kids was that they needed to be in a comfortable position and ready because of the long exposure,” he says.

“I had to warn them that because it was a long exposure if they made any sudden moves there would be a blur in the picture.

“Sometimes the blurs are nice – some of my favourite pictures have blurs in them. Inevitably you can’t control a group of between 20 and 40 people and have them all looking at the same time and looking perfect.

“You can get some horrible Francis Bacon style faces and expressions which look quite disturbing – I tend to reject pictures if someone looks strange.

“When you look at the pictures you can see subtle differences in the way people hold themselves and present themselves. There’s a lot of information – a lot to look at in every picture.”

Gradually the project extended outwards, as Germain travelled the world to shoot projects in Argentina and Brazil.

While doing his planned shoots he tried to visit schools and stayed on extra days to add to his portrait portfolio.

“I never selected schools,” he says. “When I went to do a shoot in Cologne I went to a photography book shop and asked if they knew any teachers they could contact.

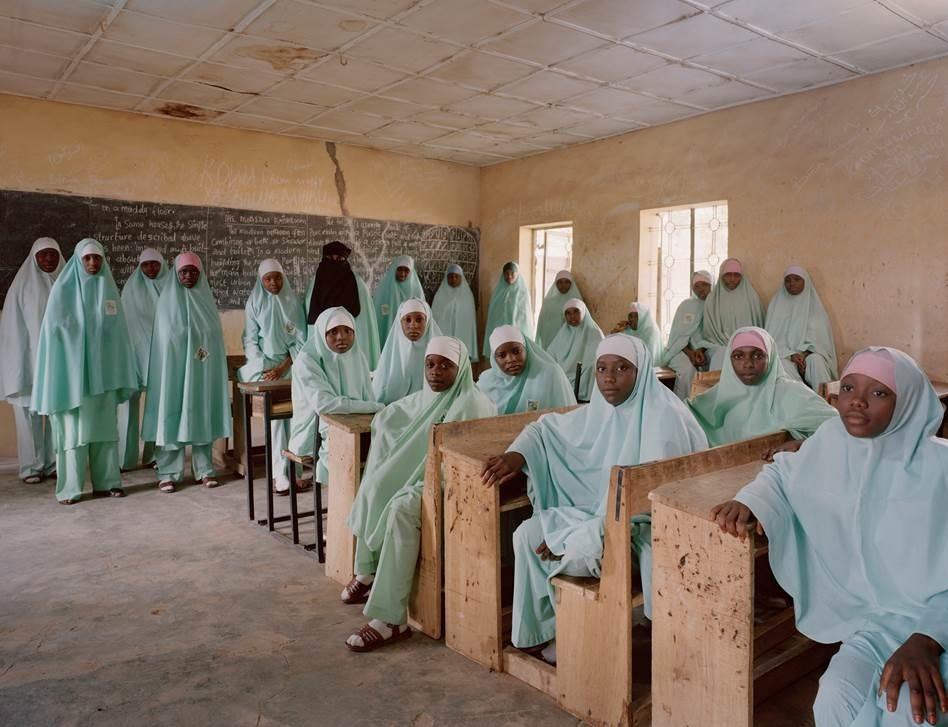

“I did some work with the British Council in Ethiopia, Nigeria, Yemen and Japan – in those cases I would give the British Council some boundaries. As well as the proactive schools they worked with in the capital cities I asked to visit a couple of schools in provincial towns.

“I got a mix of ages, primary and secondary schools, and a mix of city, provincial and rural schools.”

Some of the images have a poignancy for him – for example the girls’ school in Bahrain he shot in 2007, three years before the Arab Spring.

“I know some of them would have gone out on the demonstrations and uprisings in Bahrain,” he says.

“It stands as a historical record of what school looked like at the beginning of the 21st century.”

Although the shots come from all over the world, Germain says there are still similarities in the school set up wherever you go.

“The template is pretty much the same,” he says. “A classroom in Ethiopia is still an oblong shape with a blackboard at one end where the teacher stands. It’s recognisable from country to country.”

One link between each shot is the lack of the teacher in the frame.

“Computers are important in schools but only a teacher can hold a classroom in the way a teacher can,” he says.

“There’s the way a teacher can interact with a conversation which is much more organic than you could with a computer. A child can Google all sorts of questions, but that’s not a conversation.

“In the pictures the camera is the teacher. To have taken the shot with the teacher in it would have taken out the democracy in the pictures.”

This exhibition – which is making its UK premiere at the Towner – mixes the finished photographs with videos, books and Polaroids taken while putting together the shots.

His experiences with the classroom portraits informed another project involving extremely young people.

“I did a commission in Sunderland where I photographed newborn babies,” he says. “There are four huge portraits in a public space of babies aged four, five or six days old. I photographed them looking straight at the lens.

“I think it is an extension of the classroom portraits – the newborn babies can’t see properly or focus, they can only see blurred shapes, but you get the feeling the baby is looking straight into the camera. It’s quite challenging.”

Open Tues to Sun, 10am to 5pm, free. Call 01323 434670.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here