CineCity: Innocence Of Memories

Duke Of York’s Picturehouse, Preston Circus, Brighton, Wednesday, November 25

BRIGHTON-BASED film-maker Grant Gee’s fourth feature-length documentary gets its UK premiere at CineCity 2015.

Gee’s career began making music shorts for Sparklehorse, The Auteurs, Blur and Nick Cave. His full-length debut was Meeting People Is Easy - a documentary following the band Radiohead on the road – having connected with the band when he made the iconic video for their No Surprises single.

Innocence Of Memories sees Gee take his cameras inside Nobel Prize winning author Orhan Pamuk’s Istanbul-based Museum Of Innocence.

The museum, which opened in 2012, uses a variety of real artefacts from the 1970s and 1980s to illustrate a fictional romance as detailed in Pamuk’s 2008 novel of the same name.

The Guide: What inspired the film?

Grant Gee: It was going to Istanbul a few years back. I was completely unprepared for what an astonishing city it was.

I was reading Orhan Pamuk’s autobiographical Istanbul: Memories and the City at the same time as experiencing the city for the first time.

I left thinking I had got to come back somehow – there had to be something I could shoot so I could spend more time there.

Six weeks later I read an article about Pamuk’s extraordinary museum in the middle of the neighbourhood we had been staying in. Halfway through the article I knew I’d found my Istanbul project. I dropped him an email, and luckily he had seen my last film [Patience: After Sebald] and liked it.

How much influence did Pamuk have on Innocence Of Memories?

Obviously it was his museum, and the novel is his take on Istanbul, but it was my film in that I proposed the form. I suggested we have a female narrator leading us on a night time journey through the museum and the city, looking for a lost girl and the lost city and blurring the lines between them. Orhan wrote the narration and had input into the shape of the edit.

Going into the museum is like entering a surreal space where dreams and memories and reality get mixed up. There’s no daylight in there – it could be the middle of the night. Everything is lit by little pinpoints and spotlights. It feels magical. Coming out it is like going to a dark pub in the afternoon and being hit by everyday life when you leave.

Is Istanbul almost another character in the film?

Istanbul is like the capital city of the world – it’s at the centre of everything. New York is sometimes referred to as the capital of the 20th century, I think Istanbul is like the capital of the 21st century. There is so much art going on, and so much development with tower blocks springing up almost overnight.

Our narrator has been out of the city for 15 years, and comes back to find this museum built around a girl she knew back in the late 1970s. The city she knew has disappeared – she is trying to find it at the same time as trying to find the girl she knew.

Is the film a snapshot of a city in transition?

Orhan says the city has changed more in the last 15 years than it did over the previous 50 years. He has a studio a mile away from where he was born, and over the last 20 years looking through the window he has seen the city grow.

We shot the film over four weeks, between May and June last year, and went back for a week to pick up some shots. In that gap we found whole streets had changed – where there were once small artisan shops there was now a street of coffee bars, and three or four bridges had sprung up from nowhere. The city has grown from three million people in the 1970s to 18 million today.

You still get working class people in the middle of the city, but you get a sense that it’s not going to be like that for too much longer.

The novel tells the story of a character collecting everything to do with a love affair he has. Are you a collector yourself?

I have my books and records, but I’m not serious about collecting.

Orhan has a manifesto for the museum, based on the museums he has visited on book tours. If you go to the big state-sponsored museums what you see is the official state story of life in a city. What you don’t get is a sense of everyday life. Small museums are like novels, detailed with the stories of everyday life and the objects they touched, the wall paper that surrounded them, the TV they watched with the china dog on top.

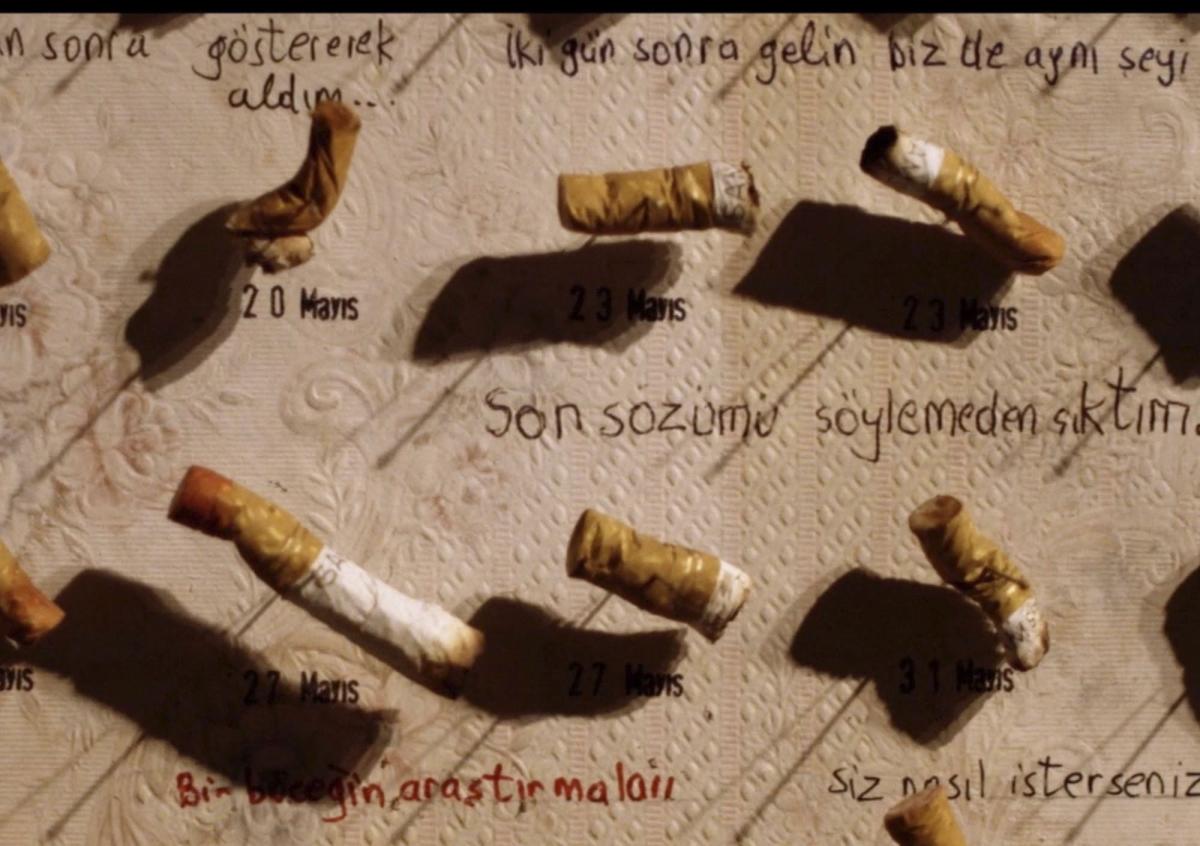

The centrepiece of the museum is a vitrine with 4,200 cigarette butts in it. What photographs don’t capture is the little captions he has written about the quality of the moment when the cigarette was stubbed out – what was being said, who was in the room. There are 4,200 slices of life – like a novel in itself.

With that level of detail how difficult was it to edit the film down?

Over the years I have developed certain tricks to block myself. With the first film I made [Meeting People Is Easy] I ended up with 200 hours of rushes – the first edit was 11 hours long!

These days I tend to edit by choosing things and putting a limit on them. If there are 78 boxes in the museum my first thought would be to spend a minute on each box to create a 78-minute film. Or to follow the audio guide, which lasts two hours – if I could make a film based around the audio guide it would last two hours. I put a limit on the film from the outset.

Have you considered working in fiction in the future?

There has always been a mix of fiction and non-fiction in my films.

I can get a non-fiction film financed on the basis of a short treatment of four or five pages and a few video clips. With a drama everything has to be nailed down before they give you the green light. You can talk about the script forever and never get the film made. With a documentary I can work with a small crew and don’t have people looking over my shoulder all the way through.

We do have a script in its second draft based on the Booker-nominated book The Lighthouse by Alison Moore. Fingers crossed that might happen.

I filmed a short performance of a Samuel Beckett prose piece a couple of weeks ago – I’m editing that at the moment to use it as a pitch for a project with Irish actor Conor Lovett making a film of Beckett’s The End.

Memories Of Innocence is about a changing city. You’ve lived in Brighton for 17 years – have you seen a similar change?

I do like the i360 – but I don’t like the stuff going on at the Marina at the moment. Brighton has changed – it’s got a bit posher – but it’s still the same place.

When we decided to move out of London the lightbulb went on when we saw Brighton. I can’t imagine living anywhere else.

Still once a week I have a moment when I think: ‘It’s really good here’.

Were you proud to have the UK premiere in Brighton as part of CineCity?

The film is opening at the National Film Theatre in London in January. I think the first idea from the distributors was that we should do a London premiere, but I put in a request to do it here.

I always think of the Duke Of York’s when I’m making a film, it’s just down the road from where I live.

I think it’s the ideal way to watch a film. I don’t think this film would work as a download. Streaming it into a different environment would really change it if I’m honest. It’s designed to be shown in a big dark room.

Starts 7pm, tickets from £10.50/£9.50. Call 0871 9025728.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here