Walking into Graham Dean’s Brighton studio – at any time, but particularly at night – sounds like it would be an eerie experience.

You’d be met with numerous watercolour paintings lying on the floor, some depicting haunting human faces, all slowly morphing and evolving as they dry. “There is a sense of the unexpected in this process,” says Dean.

“I have really no idea what’s going to happen.

“How these paintings are going to dry I do not know. I’m always checking up on them as they are always changing.”

The artist, who was born in Merseyside and moved to Brighton 30 years ago (“water runs through my life”), seems to relish the unpredictability of this approach. “When it comes down to it, I just find life much more interesting this way.”

Dean has exhibited around the world, yet strangely hasn’t displayed his work in Brighton for 20 years. He admits to not being involved at all in the local artistic community but is excited about showcasing art from his debut book, much of which was created in this city.

After studying in Bristol, Dean moved to London – “as everyone did” – and, after a spell designing paperback covers to pay the rent, started to get involved with galleries.

“The scene was nothing like it is now,” he remembers.

“There were only about five galleries in London.” At the heart of Dean’s watercolour work is a desire to subvert expectations of the form.

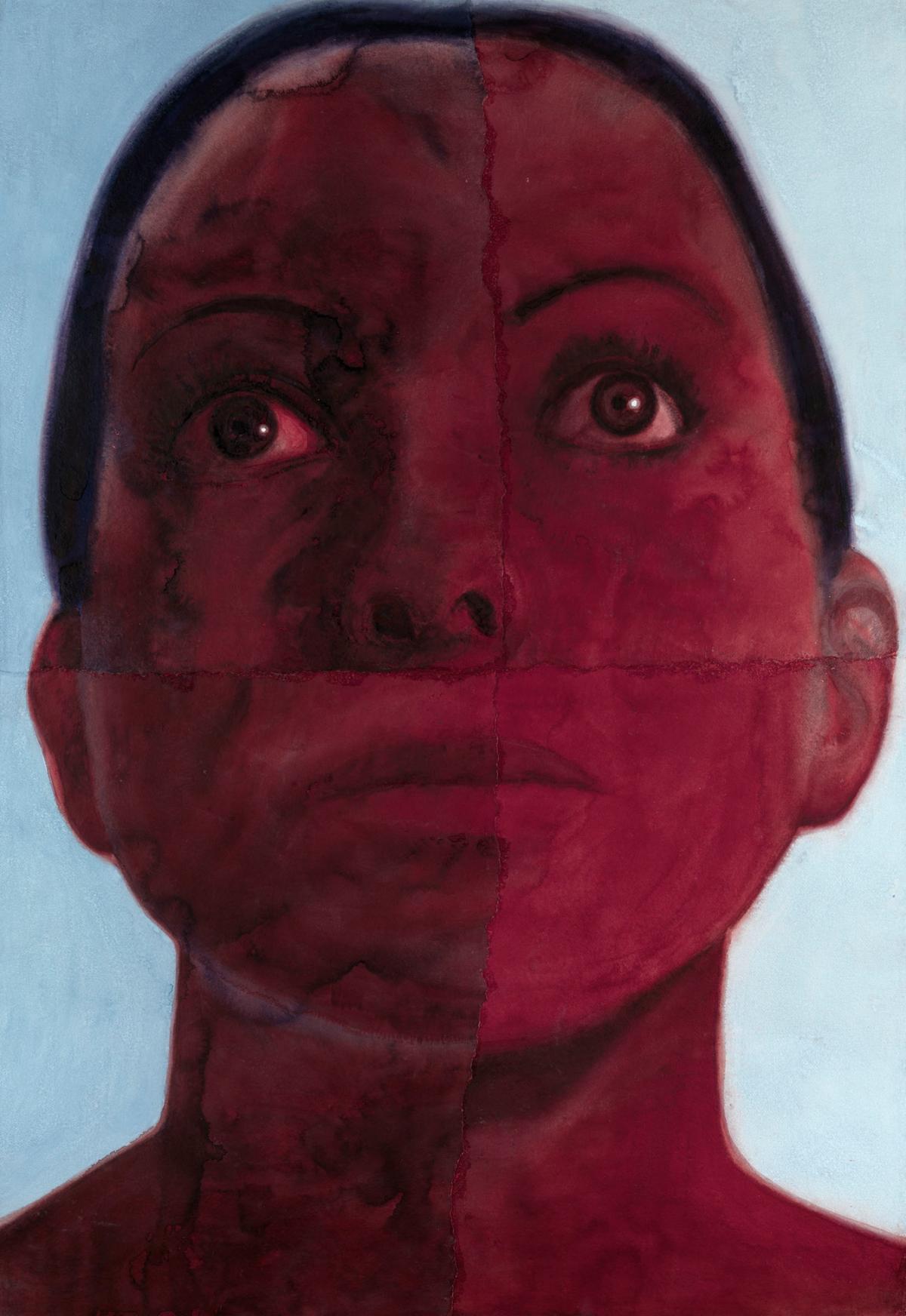

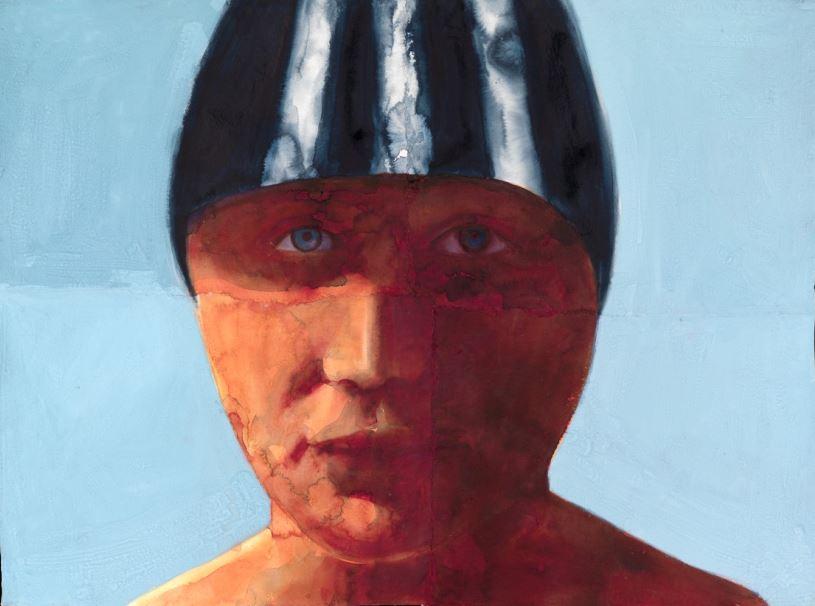

You certainly would not associate the medium with the kind of striking faces and bodies that Dean portrays – such as the simply titled Look and Trance, both pictured above.

“I needed to get watercolour away from its reputation of amateur art and flowers. I wanted to try and reclaim and reinvent the form.” He also cites a theory about artists from Merseyside that might reveal something about the origins of his occupation with the body, which he has mostly based his work around for the last 40 years.

“Artists from the area all tend to have quite a figurative basis for their work – there’s lots about the body in The Beatles’ songs, to use a popular example.”

Dean stops short of saying that nobody has ever worked with the body in watercolour before but he does suggest he is “out on my own a bit – there aren’t many artists working in the way I am.”

Having previously operated in acrylics while he was creating his early “urban realist”

paintings, Dean decided that the only way he would achieve the “visceral, emotive quality” he was seeking was through watercolour.

It took him a while to sculpt his craft and work out what the best way of optimising the form would be but listening to him explain his process now is genuinely fascinating. It was, perversely, limited resources that led him to his now trusted methodology.

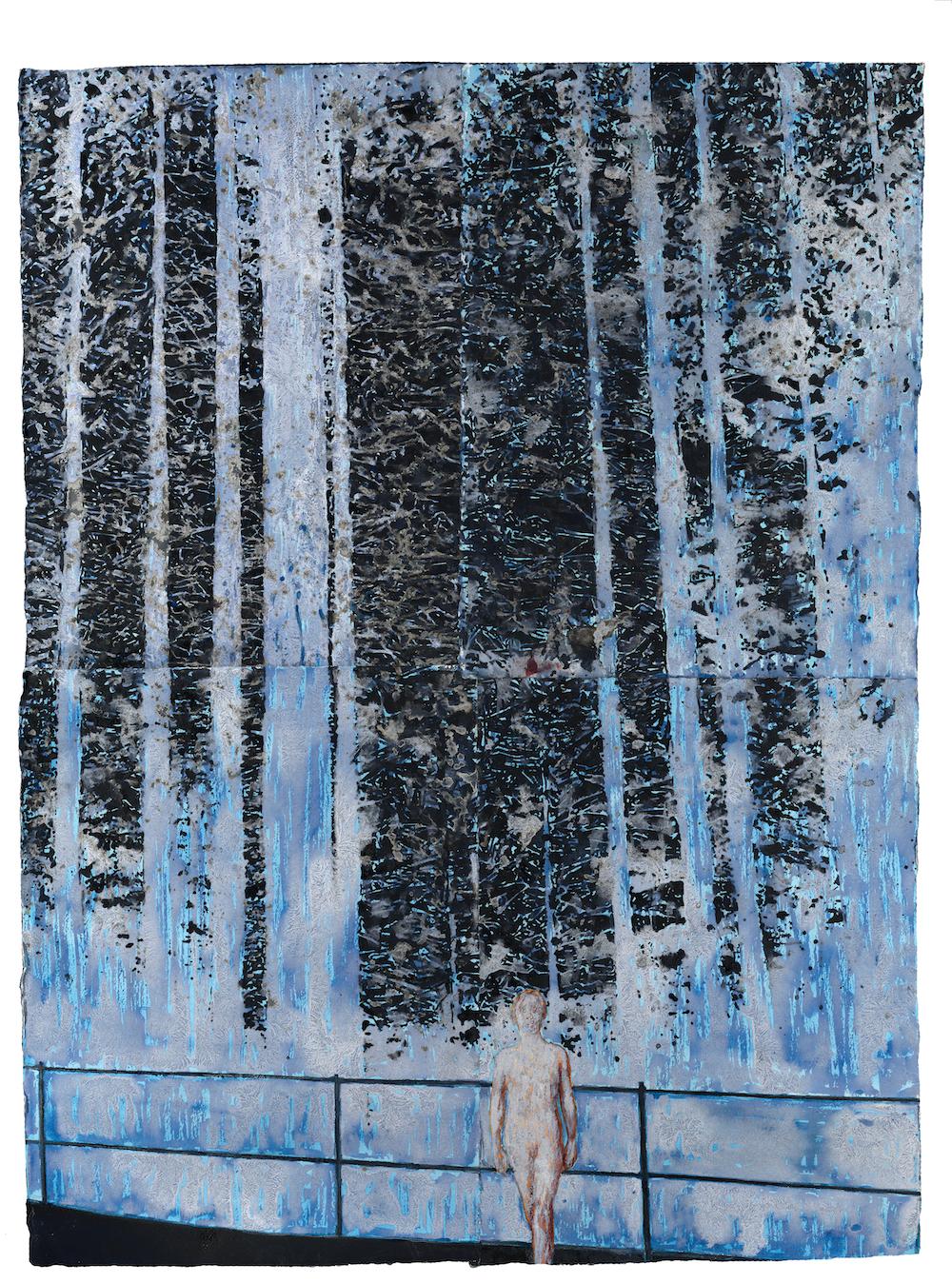

“When I started with watercolour, the maximum size you could get from shops was a single sheet, not gigantic sheets like you can get now,” he says. “But I still wanted to make really big paintings so I had to find a device to pull all these sheets together.

“I would paint different parts of the same painting on separate sheets and them assemble them together like a jigsaw or montage.

“They would overlap and then I would tear and stick the whole thing together. I still work like that – standing on the studio table, literally moving these pieces around.

“It’s like watercolour you’ve never seen before.

I turned it on its head.”

The impression this montage, piecemeal approach creates – particularly on his human paintings – is of a mask or veil.

The components of the faces are unified but also disparate and detached, having been merged together by a human hand.

It is no surprise that Dean has worked with masks before, nor indeed that he takes an interest in the philosophy of “armouring”.

He explains: “This is the idea that we as humans create layers around ourselves as protective devices. These layers can actually become negative features in our lives, though, and damage us.

“Facebook is a good example.We like to present certain images of ourselves which might not entirely be truthful or representative of how we are feeling.”

The artist says he has little interest in narrative, or telling a story through a painting, and has turned down 99 per cent of the requests he has received to create portraits of people. Instead, he tries to gain a more abstract feel for his models while making art of them. “It’s a slight psychiatrist chair kind of thing,” he laughs. “People do seem to open up to me while I’m painting them.

“I want to use my models as vehicles for a certain emotion or feel so I look for the impressions I get of the subjects.

“I’m always asking my wife ‘what does this feel like?’. It’s a very intangible thing but we know it when we see it.”

And it seems this instinctive approach is paying dividends.

If the sign of great art is that it is remembered through the ages, then Dean is apparently on the way to being immortalised.

“I get comments years later from people, saying ‘you know that image?’, I can’t get it out of my head. I think I’ve achieved something if the image sticks in people’s minds.”

Cameron Contemporary Art, Victoria Grove, Brighton, Saturday, October 8, to Sunday, November 6.

Visit: cameroncontemporaryart.com

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article