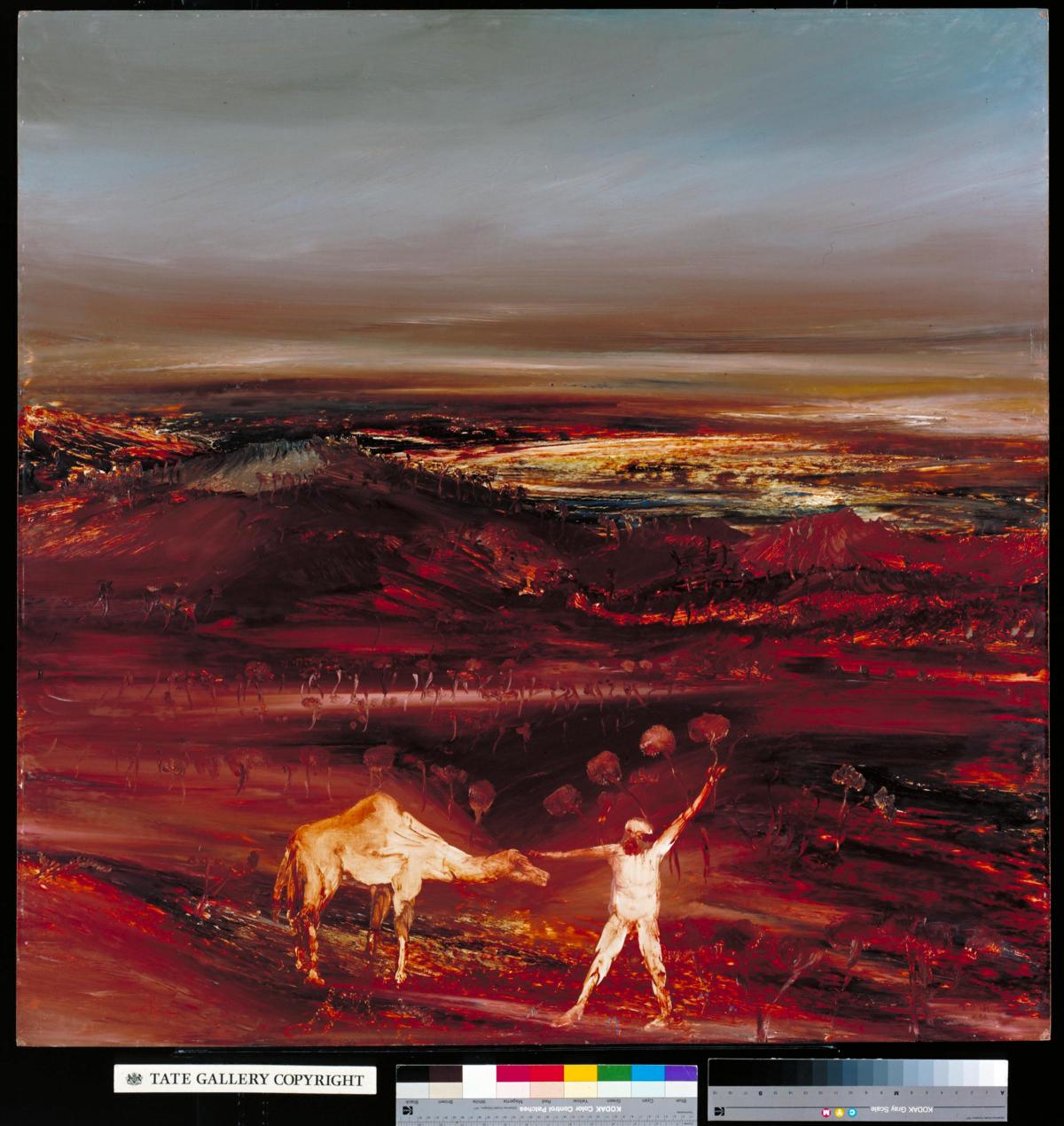

THE WORK of Sidney Nolan is simultaneously alien and human. While the wasted, scorched landscapes he portrays belong more in sciencefiction films than any terrain we are familiar with on Earth, the themes of his work – loneliness and estrangement to name two – resonate with the experience of many people in the modern world.

The haunting figures seen in some of the above pictures, and perhaps most strikingly Camel and Figure (top left), seem to suggest alienation in a strange and disorientating world; and yet many of Nolan’s landscapes are merely distorted versions of real places.

Take Inland Australia, for instance (bottom right). This painting came directly out of a period of travel Nolan undertook across his homeland in 1948. Travelling by truck, train, aeroplane and boat, the artist went in search of the Australian heartland. He was, as the Tate Modern puts it, “profoundly affected by the vast scale, desolation and silence of the desert – the second largest in the world”.

Nolan called this kind of landscape painting a “composite impression”, in that it combines observation with imagination, turning the intimidating natural terrain into an otherworldly projection. It is that amalgamation of the real and surreal that gives the work its unique, jarring quality.

Other paintings are more direct in their approach. The grotesque Carcase in Swamp (bottom left), reflects the worst drought in Australia’s history from 1950 to 1952. The cattle death rate during this time was quite extraordinary – 1.25 million cattle perished in Queensland and the Northern Territory.

In 1952, Nolan was commissioned by the Courier Mail in Brisbane to make drawings that recorded the disaster, prompting the artist to travel extensively through the worst-hit areas and taking photographs of the wasted remains of dying cattle.

It’s a grim idea but, judging by Carcase in the Swamp, it certainly has a powerful effect and helped to raise awareness of the plight of cattle at the time of the famine. Nolan had a reputation for presenting both mythology and history in his pieces, but in this work the two collide; the period of devastation became an Australian legend in its own right, aided in part by Nolan’s vivid paintings.

The artist was born in Melbourne in 1917. Over 40 years later, in 1949, his expanding catalogue of work attracted the admiration of Sir Kenneth Clark, who came across Nolan’s paintings on a trip to Australia. Clark decided that Nolan was a “natural painter” and encouraged the younger man to move to and display his work in London. Nolan, ever game for a challenge, swiftly made England his home, dying in London in 1992.

His inclusion in Lord Snowden’s book Private Views, under the chapter The Lively World of British Art, is proof that Nolan established himself as a well-respected and influential figure on these shores. The Whitechapel Gallery hosted a major retrospective of his work in 1957.

Pallant House’s exhibition features figures of notoriety from Australia’s history, including the famous outlaw Ned Kelly, of whom Nolan painted a whole series of works (one can be seen here, second left).

His depictions of Kelly in armour have become instantly recognisable staples of Australian culture. The power of his images spread abroad, too. When the series was exhibited at the Musee National d’Art Moderne in Paris, the museum director Jean Cassou called the works “a striking contribution to modern art”, adding that Nolan “creates in us a wonder of something new being born”.

Works from Nolan’s Kelly range were acquired by the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Tate Modern among others. It has been argued by art critics that Ned Kelly is in fact a metaphor for Nolan himself. The artist, like the criminal, was on the run from the law having gone absent without leave from the army.

Nolan feared he would be sent to Papua New Guinea on front-line duty so adopted the alias Robin Murray. Some claim that this selfcreated persona cast him as an anti-hero in the mould of his regular subject Kelly.

“Nolan, like this Kelly figure, has also been a hero, a victim, a man who armoured himself against Australia and who faced it, conquered it, lost it,” wrote Bulletin magazine in 1962. Others suggest that Nolan had no intention of portraying Kelly in a realistic way – only that he wanted to place him firmly into the realm of mythology.

The critic David Sylvester said: “It is no longer a question of telling Ned Kelly’s story; the picture is a myth.” Another bizarre link between the two men is Nolan’s grandfather, a policeman who was involved in the hunt for the criminal bushman.

Nolan also explored subjects that were rooted in British colonial history. The artist was coming from a strange place in that respect having moved to Britain from a colonised country. The title of the exhibition reflects Nolan’s odd position. While Nolan is perhaps lesser known than his European contemporaries, this display promises to illuminate his diverse oeuvre.

Transferences: Sidney Nolan in Britain, Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, February 18 – June 4, 01243 77455

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article