FOR its fourth incarnation Rye International Jazz And Blues Festival has taken everything up and notch.

Below Duncan Hall speaks to one of its headliners, Wilko Johnson, and highlights other big shows in the programme.

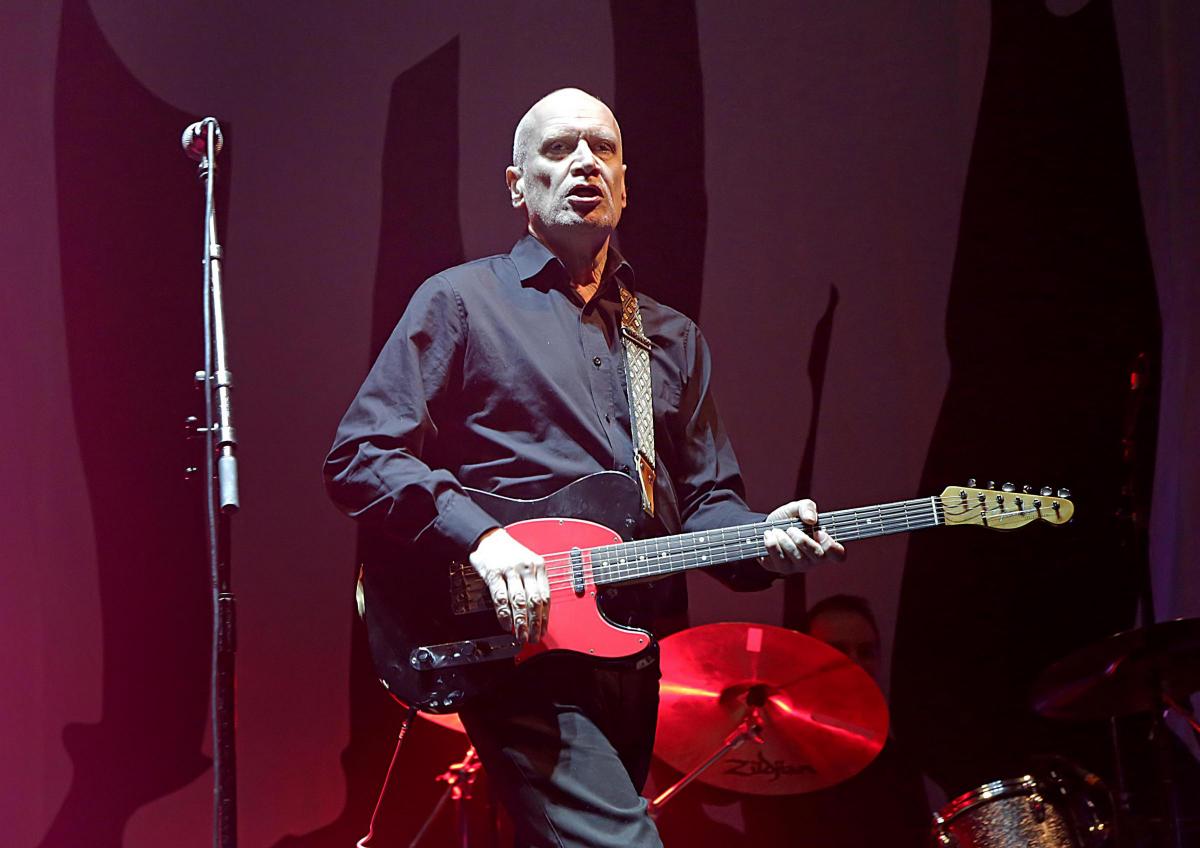

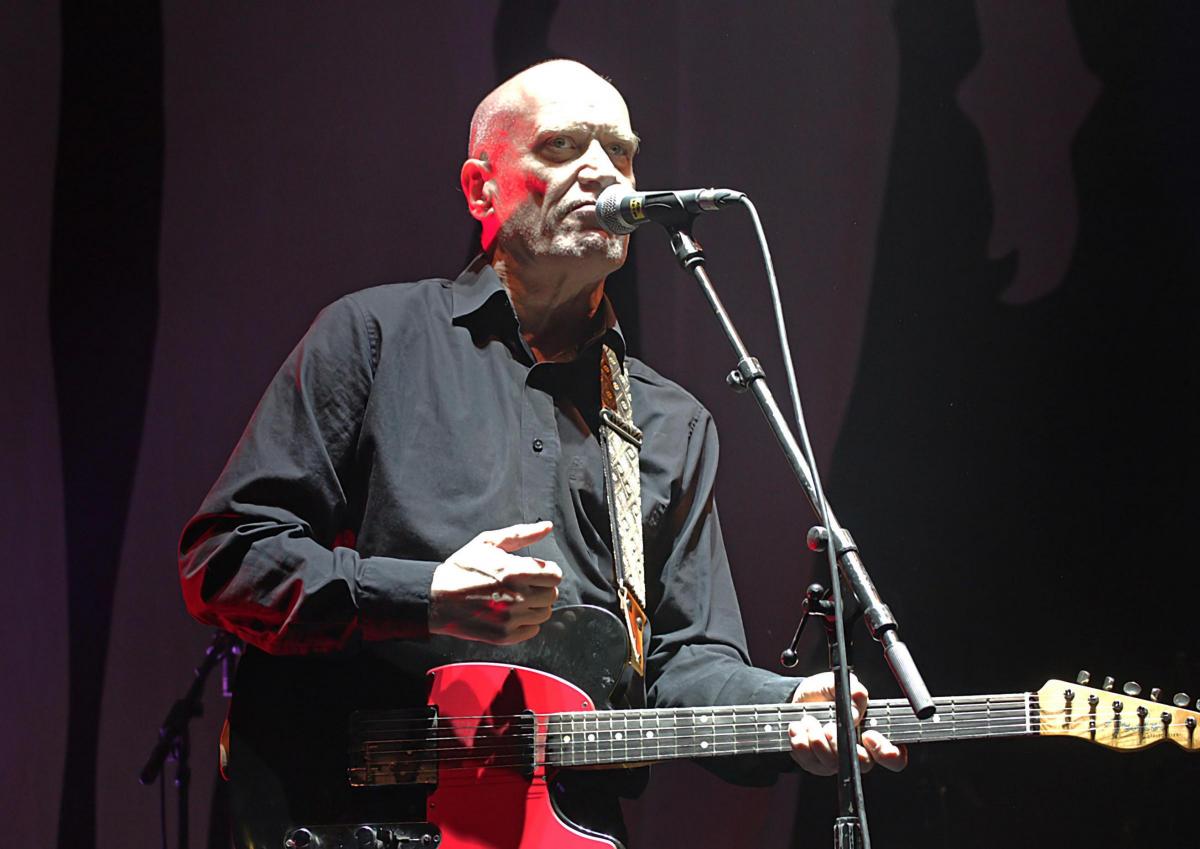

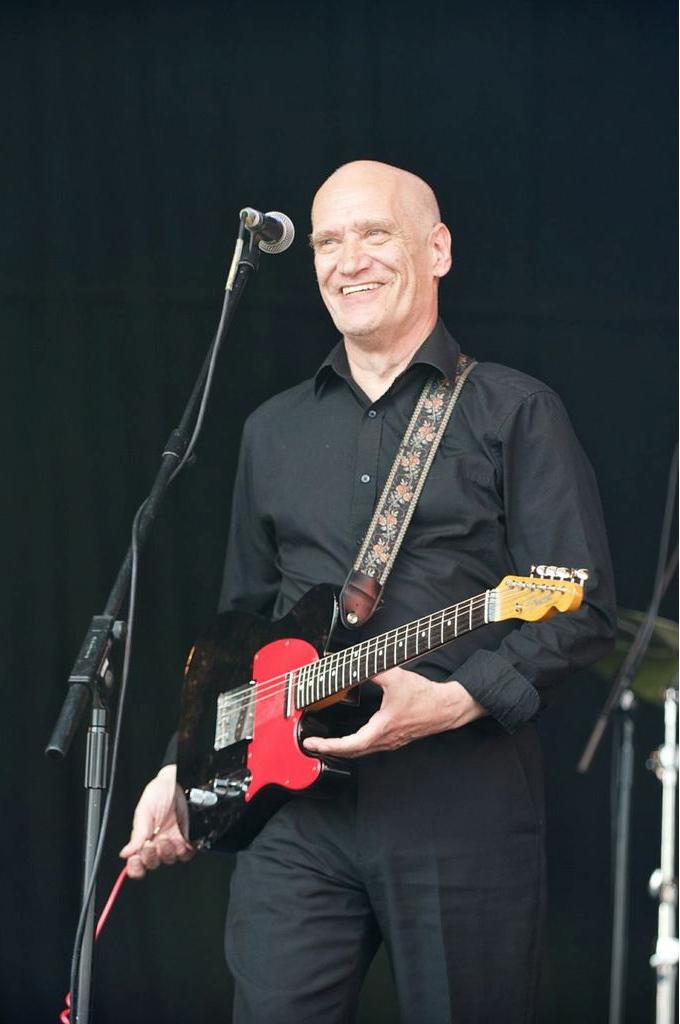

Wilko Johnson

Milligan Theatre, Grove Road, Rye, Sunday, August 30

WILD-EYED rhythm and blues guitarist Wilko Johnson may not seem like the most obvious star guest for what is ostensibly a jazz festival.

But then the same could have been said for the Cambridge Folk Festival where the former Dr Feelgood songwriter headlined earlier this year.

“There were plenty of electric things and drums and what not still going on,” he recalls from his Southend home. “It wasn’t all ‘hey nonny nonny’. I’m a huge fan of Martin Carthy, and have been for many years – his guitar playing is so great, it has feeling and he is extremely skilful. It doesn’t matter what you call it, folk or rock – if it’s got that feeling it’s good enough for me.”

Today Johnson is hailed as one of the godfathers of punk, largely for the five years he spent as a founder member of the pioneering Canvey Island pub-rockers Dr Feelgood.

While the strange time signatures and fantasy-inspired lyricism of progressive rock was filling the concert spaces of the UK, Johnson wrote songs about girls inspired by the hard-edged rock and blues he grew up with.

His no frills guitar approach combined rhythm and lead licks on one instrument, getting away from the endless solos favoured by the likes of Jimmy Page, Greg Lake and David Gilmour.

“We didn’t play London, we spent a couple of years doing our own thing in Southend,” he says. “For £2.50 you could go down the market and get yourself a black suit that looked pretty sharp. When we started we were just learning to play the music – we weren’t very good, the same as anyone else who has just started off - but we got better. We found our own slant on it.

“By the time we did start to play in London our music wasn’t fashionable, but we didn’t care – it’s what we wanted to play.

“Just to prove it all goes around in circles the drummer in my band now is Dylan Howe, the son of Steve Howe from [prog legends] Yes!”

Time spent as part of Ian Dury’s Blockheads and a dedication to playing live across the country made Johnson a much-loved figure of the UK live scene.

But it was his reaction to what was diagnosed as a terminal cancer in 2012 which took him into “national treasure” territory.

His decision not to take a course of chemotherapy and instead enjoy the remaining months he had left have been seen as truly inspirational.

And today, following a life-saving operation by Addenbrookes specialist cancer surgeon Emmanuel Huguet, Johnson admits the year and a half he spent thinking he was going to die was the happiest time of his life.

“It takes less than a second for a doctor to say you have cancer, but the universe is changed and will never be the same again,” he says.

“When they told me I was absolutely calm. It didn’t shock me at all. I would have imagined if someone said those words to me I would start running up and down and screaming.

“I lived quite near the hospital, and when I walked home I remember looking up at the trees against the sky and thinking: ‘My God, I’m alive and isn’t it beautiful’. I was tingling, the very stones in the street looked significant as I was walking along thinking ‘I’m going to die, my life is going to come to an end’. I felt so happy. It’s one of the most extraordinary years of my life – I have often found myself feeling glad it happened. It made me see a lot of sense. I was a miserable old so and so – just to think of all the troubles I thought I had in the past, it was all nonsense. I was determined to enjoy those months I had got left.”

Johnson admits he wasn’t tempted to look for miracle cures, or even a second opinion.

“In Japan this really charming couple gave me a pair of special socks – with yellow toes – which would do what medical science had failed to do,” he laughs.

“After all these years I found out how much people cared about me.”

He could see the huge tumour which began in his pancreas swelling on his stomach, but says it didn’t hurt.

“The rest of me seemed quite fit, I wasn’t losing weight and the various things you have with cancer,” he says. “It was just growing and growing. I remember asking at the hospital how long I could expect to keep on my feet, as I wanted to do a farewell tour.

“A lot of the lyrics I was singing at that time may well have been banal or whatever, but singing a line like: ‘I will love you until the day I die’ suddenly meant something more.”

He even achieved a lifetime’s ambition – recording an album with his teenage hero Roger Daltrey of The Who. The resultant album, Going Back Home, reached number three in the UK charts, and became his biggest seller since his Feelgood days.

“Years ago Roger had got in touch saying we should do an album,” says Johnson. “Nothing ever came of it, but when Roger heard about my cancer he got in touch.”

Johnson says he was “in extra time” when the eight-day recording session took place in Uckfield’s Yellowfish Studios with producer Dave Eringa. The initial ten-month prognosis he had been given by doctors had elapsed.

“I was thinking this was getting really weird,” says Johnson. “I was thinking: ‘I’m going to die soon, the last thing I’m going to do is make an album with somebody who was a hero to me when I was a teenager.

“I thought this would be the end of the story, but there were chapters yet to come.”

The recording experience dredged up memories from his past – not least an old girlfriend who had lived on a farm near Hastings.

“She had known Roger and would say I should go over to his trout farm to see him,” says Johnson. “I was too shy to do anything like that, so I never did.

“One of the songs we recorded was from that era about this bloody woman – it was so strange to hear Roger sing this thing I had written in the late-1970s, within spitting distance of where the events had happened!”

Johnson puts the sound and quality of the record down to producer Eringa.

“We didn’t have time to faff around or be sophisticated,” he says. “Dave turned this thing from a farewell bash, which is what I had expected, into an album.”

It was surgeon Huguet who changed Johnson’s life all over again.

So the story goes breast surgeon and photographer Charlie Chan, was amazed how well his old friend Johnson was doing so long after his terminal diagnosis.

He asked Huguet to review the case, who in turn discovered the tumour was treatable.

That’s not to say Johnson could be cured overnight. The resulting operation took eight hours, and resulted in Johnson’s pancreas, spleen, and parts of his stomach and intestines being removed.

He also had to be treated for tumours on his lungs and liver.

“I didn’t touch my guitar for a year after the operation,” he admits. “I was very ill for quite a long time, I didn’t really think about music.”

Initially he had envisioned leaving the hospital and travelling to Japan to recuperate, playing with long-time bassist Norman Watt-Roy at the Fuji Rock Festival at the same time.

“By the time the festival came around I was in no condition to get to Heathrow, let alone Tokyo,” he says. “I was so weak the only exercise I could do was walk around the block each evening. I had a friend who came over from Japan to look after me – she would make me do it. I would get to the corner and be worn out – hanging on the wall.

“The surgeon, Mr Huguet, is my hero. He has since explained to me that what they did the human frame is not really meant to put up with.”

When he did strap on a guitar once more it was for a benefit gig in aid of Addenbrookes.

But in doing so he had his first experience of stagefright in years.

“I was thinking: ‘Can I remember how to do it? Which three chords am I playing? Will I have the stamina to actually perform the whole show?’,” recalls Johnson.

“It certainly was a struggle, and for the next four or five gigs I was apprehensive before I went on stage, but I did it.”

He has since gone to drummer Dylan Howe’s private studio to start laying down tracks for a new album.

“I’ve quite excited,” he says. “It’s starting to happen again!”

The songwriting process hasn’t got any easier though.

“I will start with a guitar riff and then I will twang away on it over and over until I can hear it speaking words,” he says. “You find out if it’s going to be funny, if it will be a bit heavy.

“I don’t ever remember a time when I found it easy to write songs. Sometimes you will write something pretty clever, pretty fast and think ‘Why can’t I do that every time?’. TS Eliot said every attempt to write something is like a fresh raid on the inarticulate. You don’t learn – often I find myself asking ‘How did I write that?’.”

His experiences have changed his approach to life – particularly when it comes to planning ahead.

“I had decided to keep playing as long as I was fit enough to do it,” he says. “I didn’t want to go on stage in a wheelchair or anything like that. If I wanted to organise a tour I couldn’t, because it takes at least three months in advance. I had no way of knowing if I would last three months.

“Luckily it was the summer, so I was able to do the festivals. Doing those if I felt ill before a gig it wouldn’t matter, the gig would carry on and nobody would mind.

“I’m still keeping that in mind.

“All my life I have never worked to any kind of plan – I never had a manager, I just let things happen. I can’t be sure I will be alive in six months – nobody can. The difference was before I had an official document saying I wasn’t going to be.”

Starts 7.30pm, tickets £35. Visit ryejazz.com

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here