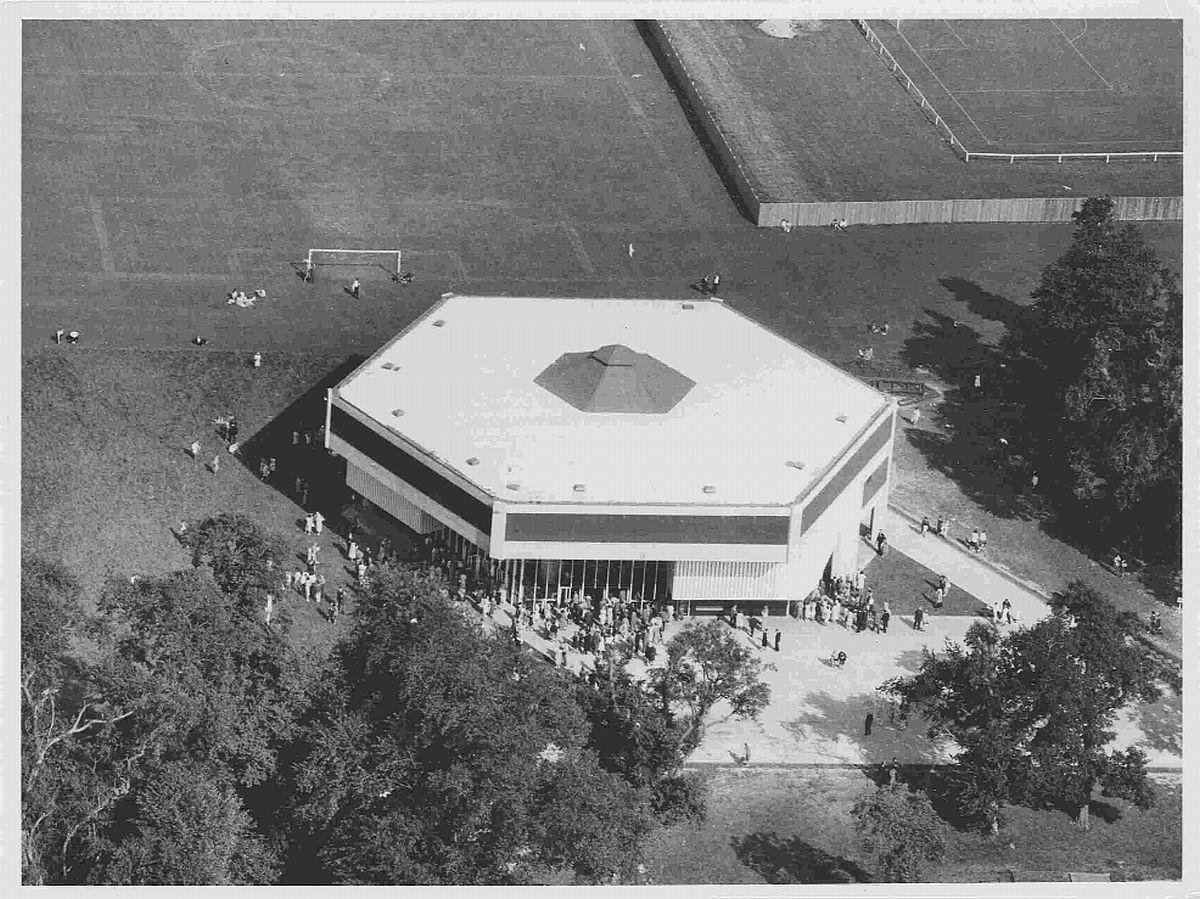

AS Chichester Festival Theatre celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2012, there were already plans afoot to ensure it survived for the next 50 years.

And executive director Alan Finch admits there were lots of jobs that needed doing.

“We knew we were committed to spending £6 million on the Festival Theatre to do nothing,” he says. “We needed to replace the wiring, improve the fire alarm system, bring more water into the building for the heating and cooling systems.

“It would have been very boring – I don’t know how we would have raised the money to do it, as no–one would have seen the benefits.”

Instead a much more ambitious project was embarked upon, rooted in the Oaklands Park theatre’s long history and origins as a public–funded cause.

The posters outside the building tell the full story of the £22 million project in three simple words: “Restored, refreshed, renewed”.

Architects Haworth Tompkins stripped away post–1962 additions to the original design. They have been replaced with two new cafes, an extended bar, a bigger foyer, and a hugely extended backstage area.

But regular Chichester theatregoers will be relieved to hear the main theatre auditorium has not lost its central character – with the thrust stage still going out to a point reflecting the building’s hexagonal shape.

“There are little bits of colour in the auditorium so it’s not quite as grey and black as it was,” says artistic director Jonathan Church. “The red is very theatrical, it gives an extra life and zing.

“The rebuilding has been mainly for the audience – and to create great work for them.”

Church admits he had to battle to keep the unusual shape of the stage: “My argument was ‘Surely Laurence Olivier stood on that point!’”

When former Chichester artistic director Derek Jacobi returned to the Festival Theatre to perform in Uncle Vanya – having been in the original 1962 cast of the play which opened the theatre – he confirmed Church’s suspicions.

“He remembered the lights going down for a blackout and rising to pick out Olivier at the point of the stage with his back to the audience,” says Church. “There’s something unique about that.”

The thrust stage was central to the original creation of Chichester’s theatre.

Opthalmic optician and former city mayor Leslie Evershed–Martin had seen a 1959 television programme about the Tyrone Guthrie Theatre Festival in Stratford, Ontario – a Canadian town with a similar population to Chichester.

His idea was to create a seasonal festival of theatre over the summer months in a space inspired by the Canadian theatre. Created by British architects Powell and Moya the 1,300–capacity Chichester Festival Theatre cost £105,000 – which was raised from town individuals and businesses.

“All of this is about the legacy of the building,” says Church. “It wasn’t built by politicians or the Arts Council, but by local people.”

The original stage floor of Canadian maple was donated by the parent theatre in Stratford, Ontario. Since the refurbishment it now adorns the backstage green room – used by both performers and admin staff – meaning they can still say they have trodden the same boards as Olivier and the fellow Chichester greats.

Meanwhile the new stage can be removed in sections for access to a 3m deep substage – giving much more flexibility to directors.

And the removal of a concrete platform at the back of the stage creates more freedom when it comes to bringing scenery into the space.

“We could make a swimming pool if we needed to,” says Church. “It has opened up possibilities of programming.”

The other big differences audiences may notice when they return to the theatre auditorium is the improved rake, the extra 100 seats in the balcony, and the better access for wheelchairs on two levels.

Backstage has been transformed from the improved aerial walkways above the stage meaning crew don’t have to crawl around in the dark, to the simplified level access to the stage, with a bigger loading lift and a roof now capable of holding six to seven tons of scenery.

“Before we had to store one show in the back, and the other one on the stage,” says project director Dan Watkins. “When we changed sets we would have to put one set on the seats. Sometimes we had to store sets in the car park under tarpaulin.

“Now we can make our space work for rep theatre. We could do three shows in rep – the way we build scenery will change.”

“The building limited the shows we could put on,” adds Finch confirming there may be the chance for triple bills in the future.

“We couldn’t change shows in an afternoon for an evening show, as it could take up to 40 people to do. Now the building will allow us to go back to having one show in the afternoon and another on in the evening.”

With views out over the park, and space for up to 41 actors to get around a dressing table at any one time, the dressing rooms have been greatly improved – offering natural ventilation and even day beds for between shows. Wigs, wardrobe and stage management teams are all in the same block, meaning admin will no longer be banished to mobile offices in the park.

The biggest differences for Chichester’s audiences will be in the main foyer – which sees the box office returned to its original 1962 position.And there should no longer be the same crush around one side of the building, while another bar sits empty and unused, as the whole airy space has been opened up.

There are two cafes – one of which will be open all day – and a theatre bar.

With toilet doors no longer opening outwards any danger of wiping out passers-by has been eliminated, and there are many more stalls.

“We have decluttered and opened up the staircases and views,” says Watkins.

Artist Antoni Malinowski has hand–painted ceilings and walls to complement the building’s geometry.

And the tarmac road outside the theatres has been replaced by paving to open it up into something resembling a piazza.

“This is a pavilion in the park,” says architect Steve Tompkins, whose company has also refurbished the Liverpool Everyman, Young Vic, Bush and National Theatre.

“Over the years more cars have come in, meaning there is less space for pedestrians. We have restored the parkland setting with landscape architects, so that in the next few years the building will be surrounded by trees, and the theatre will have a seamless relationship with the parkland beyond.”

As energy costs soar a modern building needs to be energy efficient – and many of the less obvious changes are linked to keeping heating and lighting costs to a minimum.

Lights in the auditorium are now provided by energy–saving LEDs, with movement sensitive infra–red sensors installed.

The windows are double–glazed, and both the new and old sections of the building have been thermally insulated.

But the biggest change is in the heating and air–conditioning of the building – which uses water drawn from 50m to 100m below the theatre in a ground source heat pump system.

“The water which goes through the pipes has a core temperature of ten to 11 degrees celsius,” says Finch.

“This water is used for air–conditioning for the auditorium in the summer, and in the winter, when it gets down to –2 degrees above ground we use the heat of the water to build towards a temperature of 20 degrees.”

It all helps towards the funding of the theatre – which will benefit from the reduced energy bills, increased income from the coffee bars being run by Godalming–based Caper And Berry, and the 100 extra seats in the main auditorium.As for the future Finch admits he is looking towards Chichester’s other theatre space.

“The Minerva is 25 years old this year, but we haven’t got a 25th anniversary planned,” says Finch, adding that Chichester has seen more than its share of anniversaries in recent years.

“Funds need to be raised to replace the air conditioning. My personal goal would be to see if we could create a second entrance to the theatre – we can make space by reducing the number of toilets now we have more at the Festival Theatre.”

There is also the issue of the tent, which replaced the Festival Theatre in Oaklands Park last year, hosting performances of Barnum and Neville’s Island.

“We never wanted to send the audience home while we did the work,” says Finch.

“The tent surpassed my expectations. There were a few times when we thought we had bitten off more than we could chew.”

The worst moment was just before the opening night of Barnum, when a thunderstorm looked set to throw all the company’s plans into disarray.

“We had to prepare the safety procedures for if lightning struck,” says Finch. “Everyone was put on evacuation standby, and we held our breath...”

Coincidently the new Festival Theatre was struck by lightning last week – although the only damage was to the lighting system which was knocked out for a short while.

The Festival Theatre is now in the midst of a deal with a US theatre company to sell the tent.

“Technically the tent is sold, but the deal hasn’t gone through yet,” says Finch.

The cost of the temporary theatre space had been covered in the £22 million programme of works – with Finch regarding the tent’s sale as a bonus rather than an essential necessity.

“If it doesn’t happen we will come up with another idea. We could have fun with it – perhaps a Chichester world tour?”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article