Taken At Midnight

Minerva Theatre, Oaklands Park, Chichester, Friday, September 26, to Thursday, November 1

"IF you look at the 1930s books about how horrible the Nazi regime was Hans Litten’s name comes up a lot.

“After 1945 that generation of political prisoners becomes almost a footnote because of what came next. I wanted to remind people that right from the start Hitler had a brutal regime which took out its opponents.”

Screenwriter Mark Hayhurst first brought the story of radical lawyer turned early Nazi victim Litten back to public consciousness in his BBC film The Man Who Crossed Hitler.

The TV movie told the true story of the lawyer who subpoenaed the Nazi leader to the witness stand for a three-hour cross examination as part of the 1931 Tanzpalast Eden trial. The trial was investigating a murderous attack by the Nazi’s paramilitary wing, the SA, on a dancehall popular with left-wing workers.

Hitler, then a leader of a radical party in Weimar Germany gaining popular support, received an embarrassing dressing down in the courtroom – to the point where he even refused Litten’s name to be mentioned in his presence.

But the Nazi leader had his revenge on the night of the 1933 Reichstag fire – the cataclysmic arson attack which secured the Nazi party’s stranglehold on Germany. Litten was among “enemies of the state” arrested and sent to rot in a concentration camp.

Hayhurst’s original movie ended on the night Hitler came to power – but he was inspired to return to the subject for his first stage play after researching a documentary for the BBC.

“I went to Berlin and met people who had known Litten and his relatives,” says Hayhurst. “His grand-nephews and grand-nieces didn’t know him personally, but remembered his mother.

“Litten was never charged and his case never went to full trial. For the first few weeks nobody knew where he was. His mother thought he was dead – it was only through her persistence with the Gestapo that she found out where he was.

“When I was talking to them this whole second story of this hero trying to get her son released made me think it would be a great subject for a play.”

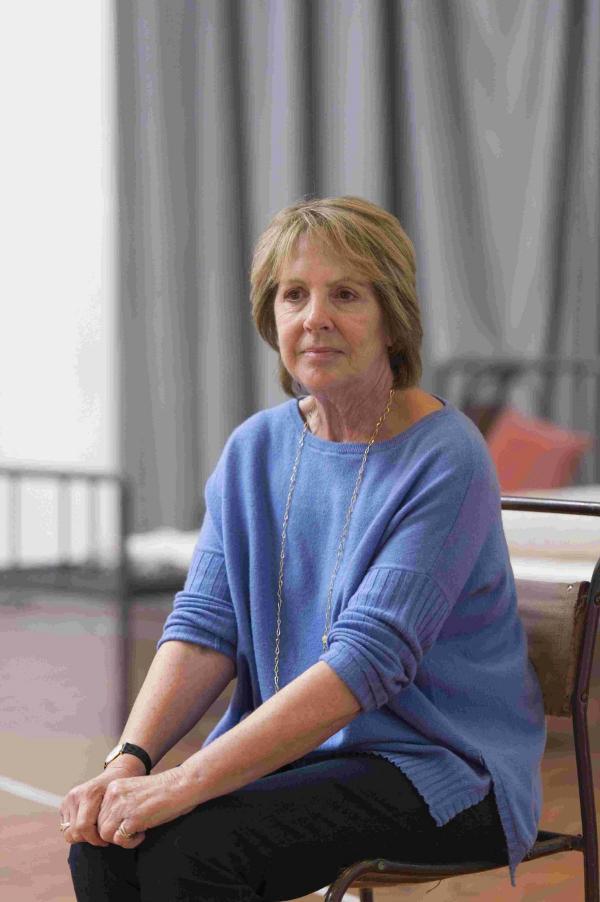

The indomitable Irmgard Litten, played in Taken At Midnight by Penelope Wilton, fought to get the Nazi authorities to take her son out of the euphemistic “protective custody” where he was regularly tortured and beaten by the very SA guards he had previously sent to prison.

“It reminded me of the mothers of the departed camping outside the secret police headquarters during the Argentine military dictatorship who would do anything to get their sons and daughters free,” says Hayhurst.

“I decided to put the focus on her – Hans Litten is very much part of the play as all this is happening to him, but the thrust of the play is provided by his mother.”

Irmgard was a lady of some standing in 1930s Berlin, which she felt gave her some immunity from the regime.

“She could quite easily have been arrested herself,” admits Hayhurst. “She didn’t have any organisation behind her – she wasn’t representing a larger body of people.

“What kept her safe was that times were favourable – after the first wave of repression in 1933 things had begun to cool off a little as Germany and Hitler tried to present a more civilised face to the world ahead of the Olympics.

“Somebody says in the play that what Hans did in the courtroom was courageous – but he says he never thought of losing. The true courage came from his mother.”

As well as telling his mother’s story, Taken At Midnight looks at Litten’s concentration camp experiences, and recreates some of the courtroom exchanges he had with Hitler – although the Nazi leader never appears in the play.

“Everyone in the play, bar one amalgam of two or three characters, is a real person – whether it is a guard, Litten or his fellow inmates,” says Hayhurst, who was able to speak to some of the people who experienced the concentration camp themselves.

“I learned about things that haven’t necessarily been published anywhere. Where they were kept there were no rules – it was pretty much carte blanche revenge for the first few weeks.

“It was miraculous that Hans stayed alive as long as he did. As the years went by the cruelty became more systematic, as the SS became the leading police organisation and the SA was pushed to one side. The violence was much more regularised to a timetable.”

Playing the role of the unfortunate Hans Litten is Martin Hutson, with Mark Grady and Pip Donaghy as his cellmates Carl von Ossietzky and Erich Muhsam.

“I wanted to capture that feeling where no-one knew how things were going to turn,” says Hayhurst. “At one point Erich is convinced the Nazi regime will only last a few weeks. He doesn’t know it is going to get so much more desperate after 1938.”

With previous screenplays covering the French Revolution, the build-up to The Great War in 37 Days and the end of the Raj in India, Hayhurst admits he has a fascination with political upheaval.

“It’s not about bullets flying and people screaming, it’s the politics of rapid change,” he says. “It’s what happens when things are thrown up in the air and the ways of doing things suddenly change. People discover good and terrible things about themselves.”

Duncan Hall

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article