It occurred to me the other day, people who write, or make pictures, or compose music – people in ‘the Arts’, we can go on forever until we drop dead because the resources we need essentially are a thing to write with or draw with,” muses John Vernon Lord.

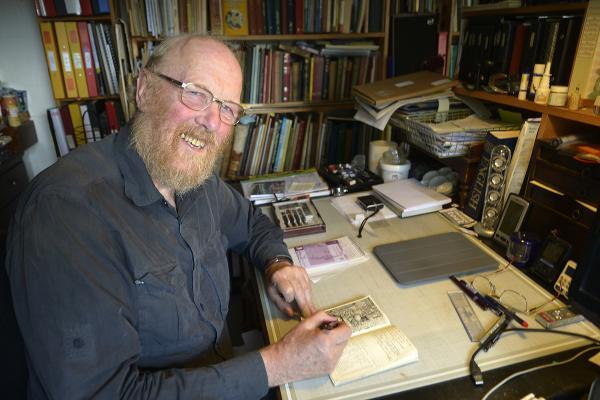

At 75, the recipient of multiple awards, and one of the biggest names in book illustration, he is very much still active in his field. A recent project saw him illustrate a Folio Society edition of James Joyce’s masterpiece Finnegan’s Wake, while his back catalogue includes Aesop’s Fables, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, and The Nonsense Verse of Edward Lear.

One of his most famous books, children’s classic The Giant Jam Sandwich, has not been out of print since it was first published in 1972.

An exhibition of some of John’s older work will be held at Holy Trinity Church, Hurstpierpoint, from September 13 to 27 as part of the annual Hurst Festival.

Many more admirers of John’s work have been given the opportunity to take a figurative peek behind the scenes, with the publication this year of Drawn to Drawing, a collection of previously unpublished material, and a journey through more than 50 years of sketchbooks, doodles and works-in-progress.

The term “doodle” is inherently misleading when applied to the workings of John Vernon Lord’s pen (he favours Rotring Isograph and mapping pens).

Even his doodles are of a gallery quality. A number of these intricate drawings were made at university faculty meetings, symbolic as the meeting point of his work as an artist and his work as an academic, but suggesting his attention was very much otherwise engaged.

Now living in Ditchling, John is originally from Derbyshire, and studied at Salford and the Central School of Arts and Crafts in London.

He has been associated with the University of Brighton for more than half a century, having started teaching illustration in 1961. He was head of the School of Design, appointed professor of illustration in 1968, and is now Professor Emeritus.

“You can be an illustrator all your life without ever teaching but if you teach you have to start to understand what it is your subject is all about, so I became an academic as well,” says John.

John insisted on picking the illustrations to be included in Drawn to Drawing himself, a task that proved more difficult than anticipated, and involved sifting through hundreds of notebooks.

“The choosing of them, trying to come to terms with what you like about your work is difficult. What surprised me is I was quite interested in some of my old work and I was sometimes jealous at what I used to be able to do.

“There’s something about youth which is exploratory, and you always try and maintain the spirit of exploration.

“I think my work is versatile enough still, but there are some past pieces that I don’t think I could do any more, and I’m sorry about that.

“One of the main things I was worried about was some of the text that I might have written in these journals and diaries revealing how naive I am, and revealing one’s silly thoughts.”

He says that, unexpectedly so, the book was a path to discovery, through the many avenues his work has taken over the years, which could explain why it has proven popular with young illustrators.

“Without any intention, I had a trendy period in the 1960s,” says John. “And of course you can’t keep on with being trendy. Trends come and go, and I have always insisted with students that you can’t rely on fashion, because fashion will change.

“It’s best to be yourself, to be individual, to have a way of working that nobody else does, and that way you can earn a living.”

John’s style is certainly distinctive, and it is his black and white pen and ink drawings that are something of a trademark.

What may not be immediately apparent is the huge amount of research that goes on behind the scenes before John produces the finished illustrations.

“For instance with the Edward Lear book, I read several biographies of Edward Lear himself to try and fathom why he was writing nonsense, and with Lewis Carroll the same. And when I did the Joyce book, the bibliography was about 30 odd,” he explains.

Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake is famously difficult, and for many, an impenetrable work of prose.

“When I was a student I was enchanted by it but I can’t say I understood it,” says John.

“I needed a lot of support from books to come to terms with it. I was given two years to do it and I took just under 500 hours to illustrate it but the big majority of it was actually understanding it.”

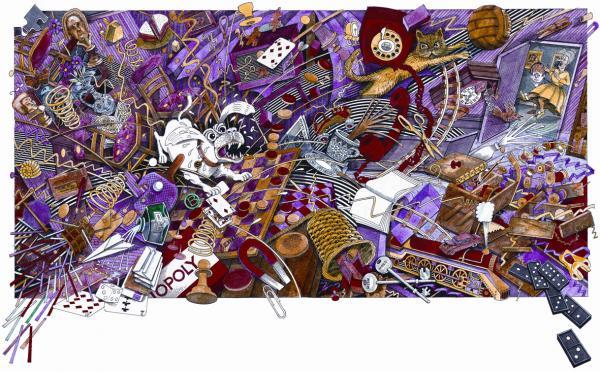

When illustrating classic texts such as Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (2009 edition), originality is the challenge.

“Because there are so many hundreds of different illustrations of it, I thought, I have got to do something slightly different.

“Alice doesn’t appear in the illustrations except at the very end, but her lack of appearance in compensated by all her text being in blue, so I thought her presence would take place in the text, just a hint, until she is real at the end because she has woken up from her dream.”

He also took points in the story that had not been illustrated before, while at the same time making sure to illustrate the parts that the reader would expect.

Two Christmases ago John was urged to start a blog by son-in-law Leo and granddaughter Freya, both illustrators, and most days since he has posted a drawing.

Some of the pieces are decades old. Some are recent, such as a sketch of his daughter’s caravan.

He describes the blog as “spilling the beans”.

“The older you get you have to interest yourself and challenge yourself to make life interesting,” John says.

He mentions an idea that he has for a graphic story of a man stuck on an island.

“The first thing he comes across is a fly. The fly is quite philosophical and it will be an odd story.

“It will probably be a little parable about how we always overlook humble people.”

- John Vernon Lord Exhibition is at Holy Trinity Church, Hurstpierpoint, BN69TY, from September 13 to 27 as part of Hurst Festival.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here