For hundreds of years Patcham was a peaceful village with fields separating it from Brighton three miles away.

Even the main railway line to London, opened in 1841, did not affect it much since there was no station and trains ran through a conveniently-placed tunnel.

Gradually, from early last century, suburbia crept towards Patcham, eventually dominating the ancient village.

Then, one fateful day in 1928, Patcham officially became part of Greater Brighton as the town extended its boundaries northwards.

The Duke and Duchess of York (later King George VI and Queen Elizabeth) arrived to join in celebrations.

Two large stone monuments called The Pylons were erected at the new boundary across the London Road part of the way to Pyecombe.

Much of the money for them was given by Sir Herbert Carden, a wealthy solicitor and former Mayor, who also arranged for gardens at the southern edge to be open to the public.

Several streets in Patcham, including the busy Carden Avenue, were named after Sir Herbert, often called the maker of modern Brighton.

In the 1930s a bypass was built so that through traffic no longer had to travel along the Old London Road. This made the main shopping area much more pleasant once again.

But at the same time the Black Lion public house became a favourite stopping-off place for motorists on their way into town.

Traffic continued to cause problems in other parts of Patcham, notably Carden Avenue, and in 1980 a Brighton bypass was proposed. This split Patcham. People living near Carden Avenue signed a petition in favour of the downland dual carriageway.

But those at the top of Patcham near the proposed bypass were strongly opposed to it, saying it would spoil their tranquillity. The road was built in stages during the 1990s. It caused less noise than might have been expected thanks to clever landscaping but equally the traffic relief was rather disappointing.

Many historic buildings have survived in the old village, notably All Saints Church and a tremendous tithe barn which has been converted into homes.

The Wellesbourne, a small seasonal river, was placed underground but in exceptionally wet winters reminds people it is still there by causing flooding.

One of the finest buildings in the village is Patcham Place, a handsome house on the far side of the London Road, which was used as a youth hostel for many years.

The suburbs now stretch all the way from the old village to near the top of Carden Avenue, almost a mile. Many of the roads have Scottish names chosen by a local developer, George Ferguson.

Patcham can also boast a clock tower at the bottom of Mackie Avenue and nearby is the Ladies Mile pub.

Modern Patcham is big enough to have its own secondary school as well as those for younger pupils. It also has a thriving community centre.

There was some opposition to the creation of Brighton’s only site for travellers at Horsdean but it causes few problems.

Occasionally on a Sunday morning, peace returns to Patcham but at most other times it is more north Brighton than an old village.

Looking back

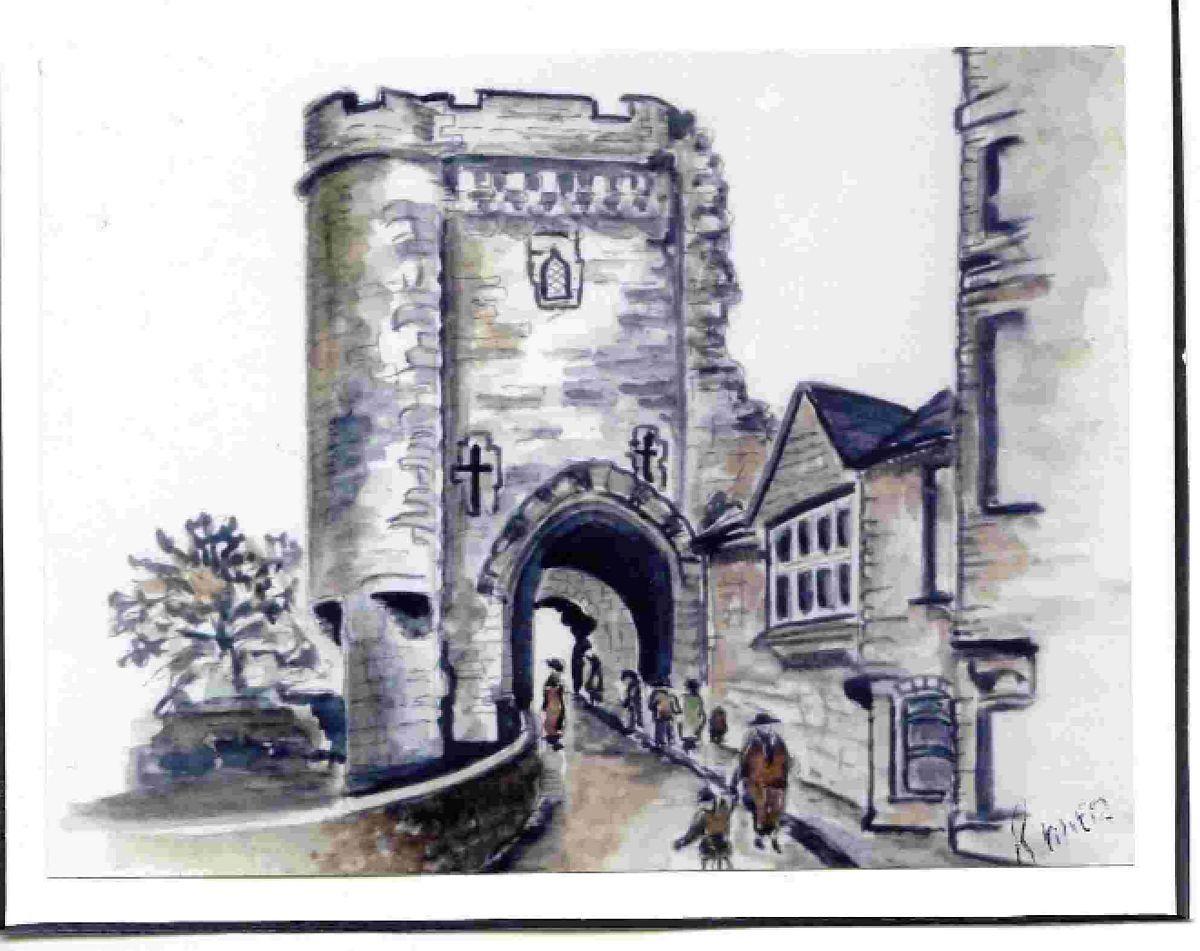

This picture of Lewes Castle was painted by veteran Hove artist Rupert Maher of Old Shoreham Road.

His grandfather used to take him here when he was a child and years later he returned to depict the castle from the High Street.

The castle was built in 1069 on the highest point in Lewes and dominates views of the town especially from the south. It featured last year in commemorations of the Battle of Lewes 750 years earlier.

Given to the town by philanthropist and former Brighton Mayor Sir Charles Thomas-Stanford in 1922, it is open to the public thanks to Sussex Past.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article