AT 2.54am on October 12, 1984, an explosion echoed across Brighton and Hove. The events of that night would be felt across the western world for years to come. Reporters BEN JAMES and FLORA THOMPSON look back at the biggest news story this city has ever seen.

A MONTH before the deadly terrorist attack a man called Roy Walsh checked into The Grand.

He stayed for four days in room number 629, seemingly doing nothing more than enjoying the tail end of the summer season.

But Mr Walsh was not Mr Walsh. He was Patrick Magee, a provisional IRA activist tasked with murdering the then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and as many of her cabinet members as possible.

He planted a bomb with a long-delay timer made from video recorder components and a memo park timer safety device – the type seen in egg timers.

It was packed with 20lb of gelignite.

Magee checked out and the 1984 Conservative Party conference checked in.

Security searched the building and sniffer dogs worked their way through the hundreds of rooms.

But despite the caution, the bomb was not discovered.

It is believed the dogs did not find the device because of the cling film wrapped around it, masking any smell of explosives.

The conference began and the leaders of the country came and went – while all the time the deadly bomb was ticking down.

Then in the early hours of the morning of October 12, a deafening blast blew a hole in the front of the Victorian hotel.

Bricks, debris and glass shot through the air as the midsection of the building collapsed into the basement.

Five were killed and dozens injured. Mrs Thatcher, who was awake at the time working on her conference speech, was unharmed.

She was taken, with her husband Denis, to Brighton Police Station before being taken to a safehouse.

This was the most audacious attack on British democracy since the gunpowder plot. It was a day that those involved would never forget.

Norman Tebbit, the then secretary of state for trade and industry, was asleep in his room with his wife when the bomb went off.

Speaking this week, the now 83-year-old said: “It woke me up and then the chandelier started swinging and ceiling fell in.

“We were covered in debris, we were completely covered – we were pinned down.”

Trapped by bricks and pieces of furniture, it was a number of hours before the emergency services got to the Conservative MP and his wife Margaret, who was left permanently disabled as a result of the blast.

Asked if he was panicking, he said: “What’s the point in panicking. I was just thinking, I hope somebody gets me out before I bleed to death.”

The photograph of Lord Tebbit being carried out of the devastated building is one of the enduring images of the day.

He was taken to Royal Sussex County Hospital where doctors asked if he was allergic to anything. The defiant cabinet minister replied “bombs”.

He was later transferred to Stoke Mandeville Hospital in Buckinghamshire where he remained for several weeks.

Across Brighton and Hove the explosion had woken many and even set off car alarms.

Argus photographer Simon Dack had just got to sleep when he heard the blast.

He said: “I turned to my wife and said it sounded like a car backfiring. She said it sounded like a bomb.

“The next thing I knew I was on the phone to one of our reporters, Phil Mills, who told me that The Grand had been blown up.

“I had been at the hotel earlier that night to have a drink with a few photographers, I couldn’t believe it.

“I got in the car and rushed down. The whole place was lit up with emergency lights. I parked up at the bottom of West Street and just started taking pictures.”

He was met by then Argus reporter Mr Mills who had rushed down with his pyjamas under his clothes.

Mr Mills said: “My wife heard the phone ring and she prodded me in the ribs – it was The Argus newsdesk telling me something that I initially thought was part of a dream: A bomb? At the Grand?

“I threw on clothes over my pyjamas (thinking it was a hoax and that I’d be back in bed in an hour) but as I drove into town and saw a convoy of emergency vehicles speeding past me I realised this was real.”

He met up with Mr Dack and fellow Argus reporter Jon Buss before splitting up to speak to whoever was in a state to answer.

“I followed the trail of masonry that had snapped off a flagpole on the opposite side of the road to the hotel and met a couple who had been sitting on the beach. The young man said: ‘Bit of the pole and brick flew over our heads – the explosion was deafening’.

“The then education secretary Sir Keith Joseph was in total shock in his silk dressing gown, in the lobby of the nearby Metropole Hotel: His answers were mumbled and jumbled. Nigel Lawson (in his pyjamas) was more coherent. All were in a state of disbelief.”

Mr Mills was one of the first on the scene and just minutes after arriving he had started filing his copy back to the Argus office.

But not all the journalists at the conference had been as quick off the mark.

He said: “I was sending copy from the lobby of the Old Ship when another pyjama-clad man exited from the lift and demanded receptionists tell him what was going on. He was the Washington Post reporter who had slept through the explosion and the first he knew anything was when his phone rang – it was his newsdesk asking when he would be filing copy.”

Mr Dack added: “It was the biggest story in the country for a long time and the biggest ever in Brighton. But at the time it didn’t seem like that. There were all these rumours flying around about who was dead and who wasn’t.

“I was just worrying about taking pictures. My biggest concern strangely was getting the pictures back to the office. We would have to get to a phonebox and call in a despatch rider to take them. I was there all night and the next day just taking pictures.

“I don’t think I went back into the office for a couple of days.”

Jennie Dack, Mr Dack’s wife, had her own experience of that historic morning.

She was working at Marks & Spencer in Western Road and was called to open up early so the delegates could buy new clothes.

She said: “They were wandering around in their pyjamas all looking like ghosts. They were covered in dust and were clearly shocked at what had happened.

“It was a very surreal experience and a very strange atmosphere.”

Five had been killed. Eric Taylor, North West area chairman of the Conservative Party, Lady Jeanne Shattock, wife of Gordon Shattock, western area chairman of the Conservative Party, Lady Muriel Maclean, wife of Sir Donald Maclean, president of the Scottish Conservatives and Roberta Wakeham, wife of Parliamentary treasury secretary John Wakeham.

Perhaps the most high profile to be killed was Sir Anthony Berry, then MP for Southgate. The 59-year-old was with his wife, who was badly injured.

His daughter was in London staying with her sister and remembers the moment she turned on the TV news that morning.

She said: “These were the days before mobile phones so we were waiting around for information.

“We didn’t really know what had happened or if he was there or not. We were just hoping for the best.”

It was several hours before they received any news, and when they did it was the news they had dreaded.

She said: “We got a call in the afternoon and told his body had been identified.

“I was 27 at the time and it changed my life forever, we were all devastated.

“I remember this feeling of disbelief, it was so hard to take in.

“Shortly after his death I got a letter from him. I had been living in India and the letter had gone out and then come back. When I opened it I forget for a minute that he had gone.

“It was a very difficult time, just a few months before my uncle had killed himself and then this.

“Everyone rallied round and I remember us trying to be strong at the funeral. We wanted it to be a small event so Margaret Thatcher didn’t come.

“Princess Diana, (Sir Anthony was her uncle) was also there. I remember her coming up to me and saying what a fantastic man my father was and how she was so sorry.”

Despite the utter devastation, Ms Berry decided something positive had to come from the death, fear and destruction.

Patrick Magee was convicted for five counts of murder and told he would serve 35 years minimum.

However, he was released having served just 14 under the terms of the Good Friday Agreement.

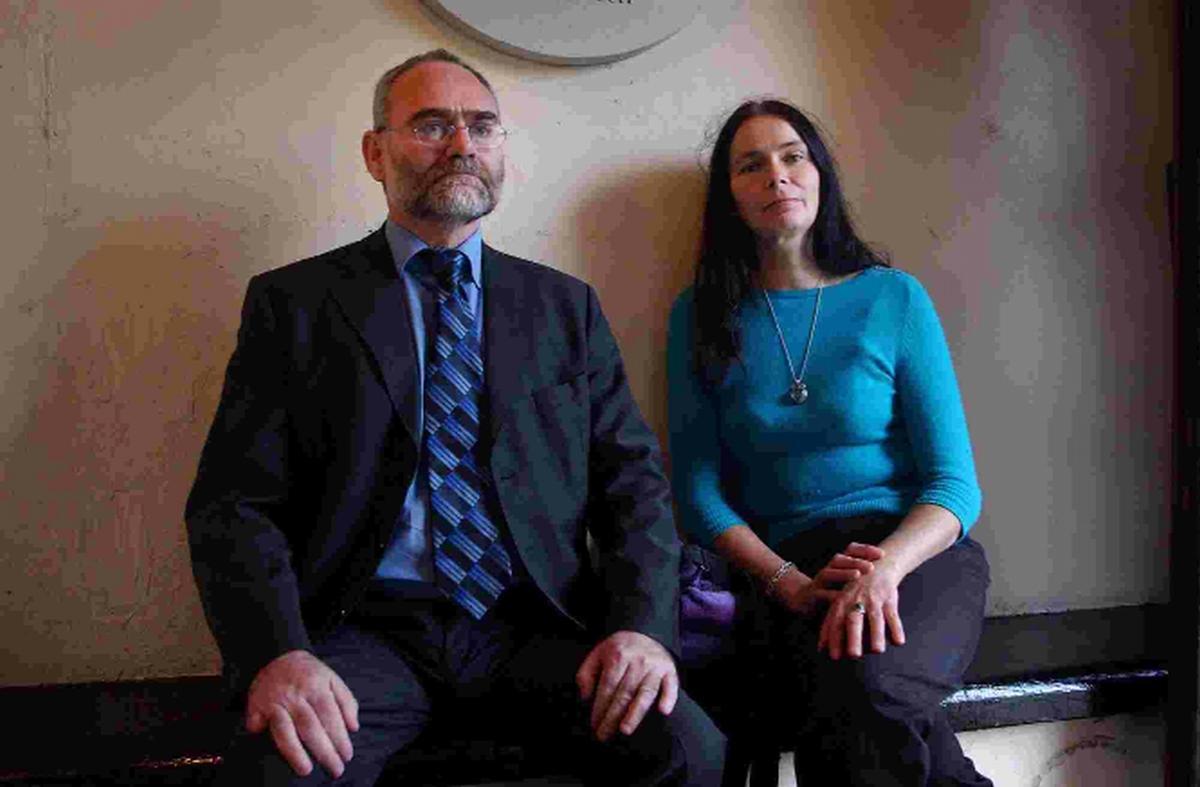

Shortly after his release, in November 2000, Ms Berry met with her father’s killer – sparking criticism from some families of victims of IRA attacks.

They went on to meet a number of times over the following months and a documentary about the meeting was broadcast in December 2001.

She now speaks around the world on the topic of peace building and reconciliation and has launched her own foundation, Building Bridges for Peace.

She will appear with Mr Magee at an event at the Old Market Theatre, Hove, on Sunday.

She added: “Just days after I decided I had to do something positive. I am proud of what I’ve done but I still feel like I need to do more.”

Ms Berry added: “I would say he is a friend (Magee). It is an unusual friendship but I care about him.

“I am always going to be against any violence but if I understand why he, and others, chose to use violence then that can help me to look at how we can make the world a place where people are less likely to use violence.

“Forgiveness is such a difficult word. But he is my friend now. We spend a lot of time together."

She added: “He regards me as a friend. He knows that my dad was a wonderful human being and he knows that some of the qualities I have came from my father and that weighs heavily on him.”

• Sir Andrew Bowden breaks his silence...

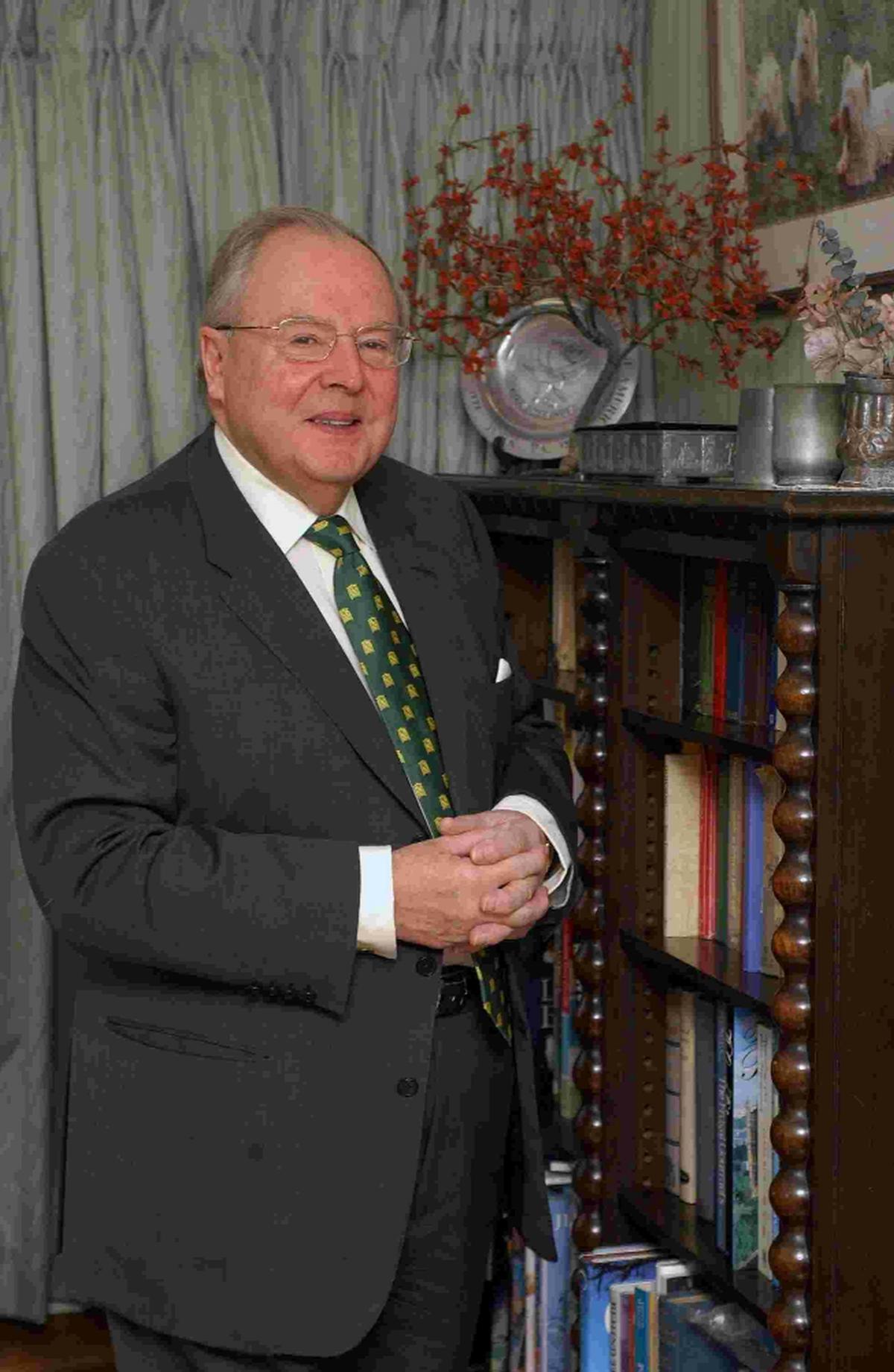

UNTIL now the then Brighton Kemptown MP Sir Andrew Bowden had kept silent about his experiences that historic morning.

Now, on the 30th anniversary of the attack, he speaks exclusively to The Argus about how he rushed to the aid of Margaret Thatcher.

He said: “It is an evening of my life which is seared into my mind. I have deliberately held back from speaking about this because I did not feel it was appropriate until now to explain my involvement in the events.

"I do think fate played a part and to some extent it was destiny.”

He said the release last week of the Iron Lady's private papers by the Margaret Thatcher Archive Trust seemed like a fitting time to share his recollections.

Details of how Baroness Thatcher calmly took time to personally cancel a hair appointment at a Hove salon were among the revelations published about her actions after the bombing.

Sir Andrew, 84, who now lives in Ovingdean, said it was “fate” he was not in The Grand at the time of the bomb.

“I left at about 1am and walked home - I lived not far away in Sussex Square at the time.

“My wife was still awake when I got in and we chatted about the evening's events before going to bed.

“And it was not long before we heard a deep boom, like thunder. We thought 'what the devil was that?' and ten minutes later the phone rang.”

A senior police officer told him an attempt had been made on the Prime Minister's life. He was summoned to her side as she took shelter at Brighton police station.

Sir Andrew said: “I threw on my clothes and dashed down to the Edward's Street station where I was taken straight into the chief superintendent's office. She was there, sitting in the chief superintendent's chair and surrounded by chief constables and senior officers.

“I rushed over to say 'Prime Minister I am so sorry' and she immediately said 'Andrew, I am alright' which amazed me.”

He added: “I had been involved in the security in the run up to the visit and we had identified a number of safe houses in the area, a couple in Brighton, one in Lewes and one in Rottingdean.

“The officers and I were debating the best place to move her and I saw she was beginning to get irritated.

“She was tapping her fingers on the desk and suddenly banged her hand down and said, 'Gentlemen, I have sat here listening to this discussion for some time and a decision needs to be made. I do not mind where you take me but there is one clear instruction. You must have me back at the conference centre by 9am. Is that understood?'.

“She showed remarkable courage.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel