SUSSEX played a key role in the First World War, with every man, woman and child in some way involved. Historian IAN EVEREST will speak about the subject at a special event on April 7. Here he gives a preview of his talk on Sussex and the so-called war to end all wars.

One hundred years ago the First World War was in full swing.

The high hopes of a speedy conclusion to the war and the safe return of the troops had been shattered.

With its relatively close proximity to the front line, Sussex played a major role in sustaining the war effort.

Its ports, its railways, its vast tracts of open downland and the availability of an assortment of large buildings transformed parts of the county into a warfare supply depot, a training ground for troops and a reception centre for the war wounded.

The port of Newhaven, and its connection to the railway network and the capacity to bring loaded trucks alongside the ships, became one of the major supply ports for the Western Front.

Working 24 hours a day, seven days a week, a labour force of some 2,500 men and women loaded an assortment of supplies including ammunition, guns, vehicles, food for the men and hay for the horses.

Many of the workers came from Brighton and Lewes and a special train was run every day to coincide with the three shifts. It was known as the “Lousy Lou”.

On July 19 1915, the Times Newspaper published an article which had quite an impact on Newhaven – and later the rest of the country.

Newhaven was the first town in the country that would have drastic restrictions placed on the sale of alcohol.

Following years of relative licensing freedom, when ale-houses could open as early or as late as they pleased, the times of permitted consumption were to be controlled by the government.

Apart from these new opening hours, no one was permitted to a buy a drink for another person and publicans were forbidden from offering credit.

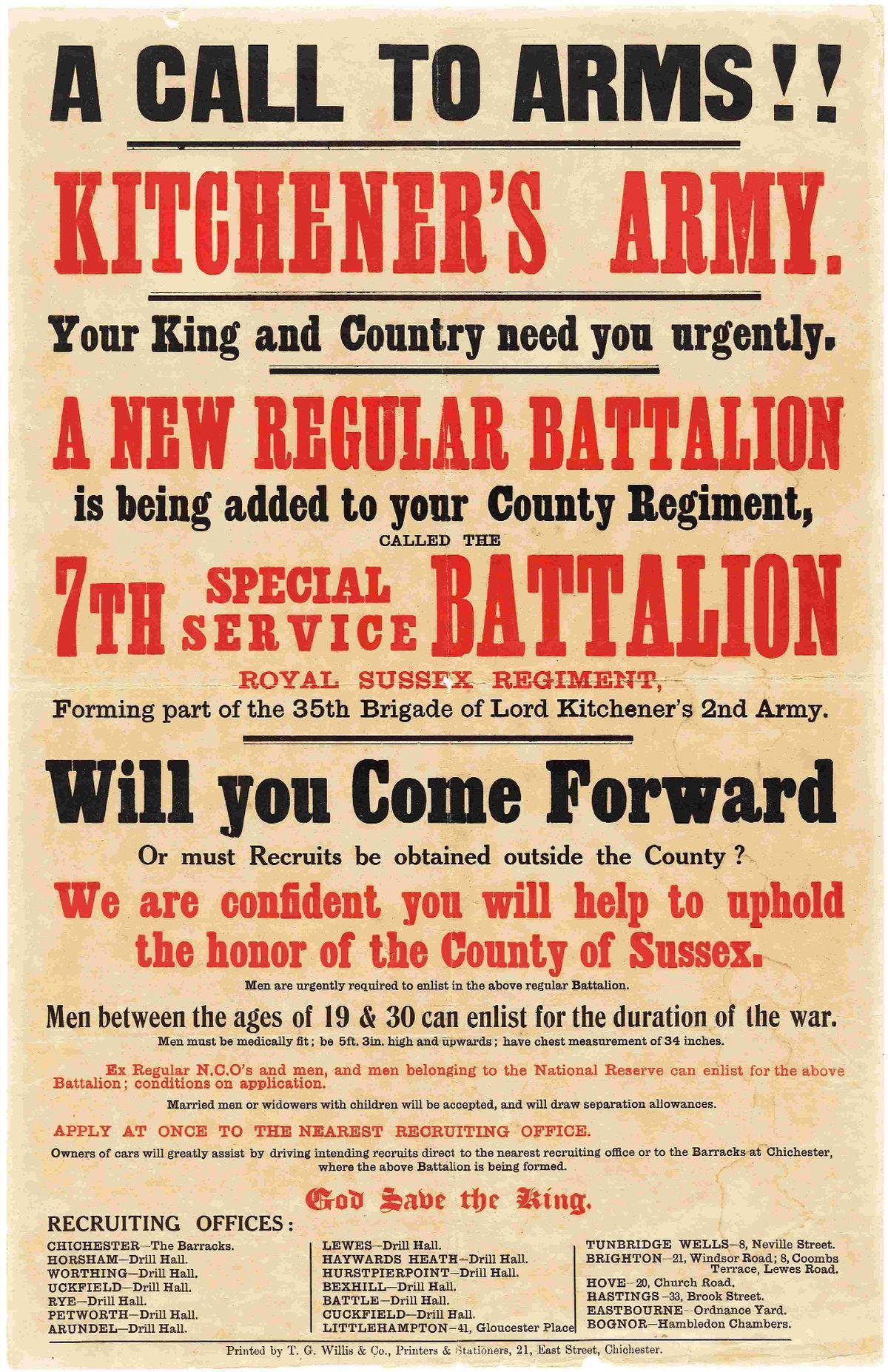

New battalions were formed, which included the three Southdown Battalions, with men recruited from the towns and villages of Sussex.

Colonel Claude Lowther, of Herstmonceux Castle, played an instrumental part in their formation and his battalions became known as Lowther’s Lambs.

In November 1914, farmer John Passmore, of Applesham Farm, Lancing, presented them with an orphaned Southdown lamb which became their mascot.

On June 30 1916, this assortment of Sussex men, including farm and estate workers, took part in the Battle of the Boar’s Head in Northern France.

Seventeen officers and 349 men were killed, with more than 1,000 men, wounded or taken prisoner. The day became known as The Day Sussex Died.

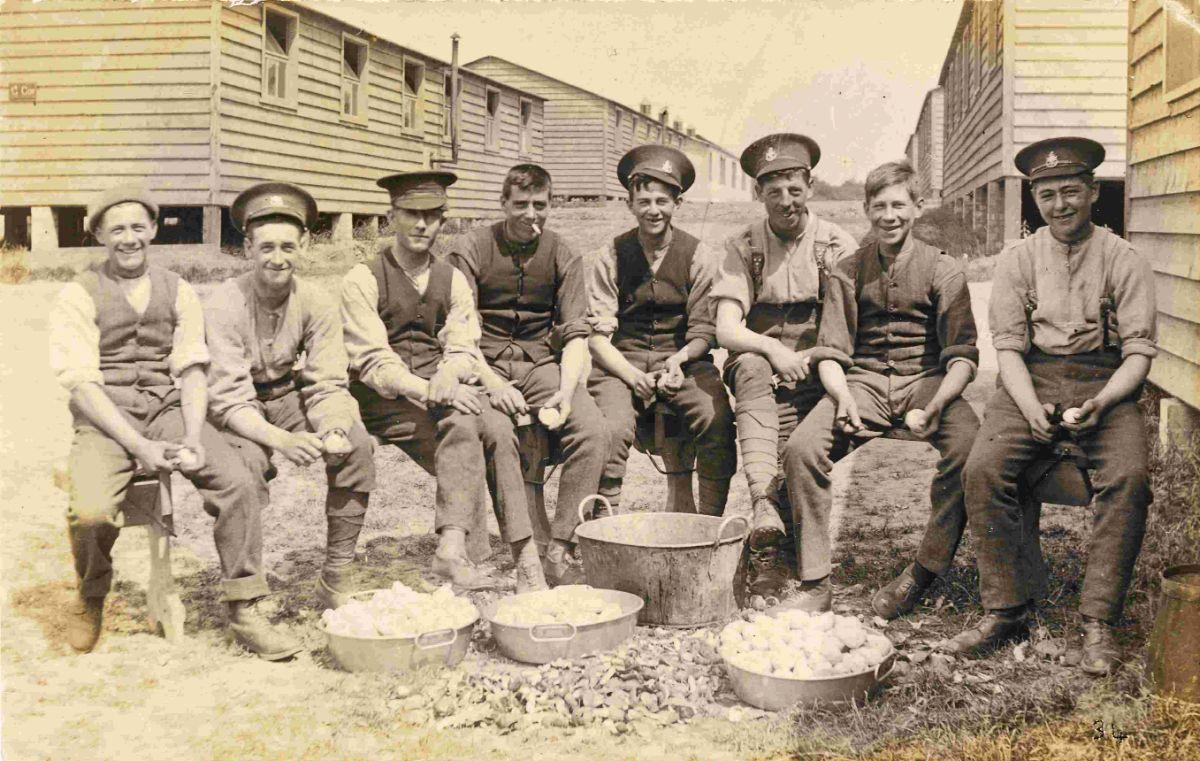

Central to the recruitment of men was the setting up of army camps. Seaford and Shoreham were chosen as camps for Lord Kitchener’s volunteer army with both towns witnessing thousands of men passing through on their way to the front line.

More camps were set up in Newhaven, Maresfield, Crowborough, and Cooden.

The treatment of the war wounded saw military hospitals established in Brighton, Chichester, and East Preston.

Auxiliary hospitals were set up in schools and small and large private houses, both in the countryside and the towns.

At Eastbourne the vast Summerdown Convalescent Camp opened one hundred years ago in April 1915. Its main aim was to get the men fit enough so that they could return to the trenches.

Despite Sussex playing this support role for the Western Front, it was still predominately a farming county.

The majority of the farms were grassland, with dairy cows, beef and sheep. With few farmers growing cereals due to the low prices and the high level of imports, Sussex farmers were asked to plough up grassland and grow wheat.

Farming was not in a good state in 1914. There had been little mechanisation and farmers relied on horse power, but many of the best horses were taken away by the army.

On the coast between Seaford and East Dean, oxen were still being used to plough the land.

The distinct lack of tractors forced the government to place an order for 5,000 tractors from America.

The order was placed by the Ministry of Munitions and the tractors became known as the MoM tractors.

Sussex was the perfect place to use these tractors, with the large open spaces on the Downs, and one was used by farmer Edward Gorringe at Chyngton Farm Seaford.

The strange sight of these large and heavy tractors on the Downs was made even more unusual when the Women’s Land Army was formed in 1917 and women began to replace the men who had joined up.

Mr Gorringe was not impressed with the tractors, however, and said that they keep jumping out of gear. His idea of farming was to continue to use his beloved oxen, remarking: “Oxen are the real Sussex.”

Many of the Land Girls in Sussex became part of the Forage Department.

The million or more horses on the Western Front needed feeding and Sussex was in a perfect position to help.

Using steam-driven machines, the women travelled from farm to farm making hay from grass that had been requisitioned by the government.

The hay was compressed into heavy bales and tied together by steel wire.

No one living in Sussex could escape the fact that Sussex was playing a major part in the war.

The evidence was there for all to see: the railway carriages trundling through the countryside and delivering continuous supplies to Newhaven, the airships and aeroplanes protecting the shipping convoys and the train loads of the wounded arriving on the coast.

If anyone had not noticed these things, then their ears would have reminded them of what was happening over on the other side of the English Channel.

In June 1916, 20-year-old Arthur Gurr, one Lowther’s Lambs, died of his wounds and was buried in the churchyard at Isfield.

A reporter for the local newspaper wrote: “The scene in the little churchyard was one which will live in the memory of many who were present. The sound of the guns on the distant Front was distinctly audible and overhead, a reconnoitring aeroplane hummed steadily.”

- Mr Everest’s talk “Sussex During the Great War” will be at the Hillcrest Community Centre, in Hill Crest Road, Newhaven, on April 7 at 7.30pm. The talk is part of a Newhaven Historical Society event, although guests are welcome. Entry costs £2.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here