AMBITIOUS plans for a £200million eco holiday park at the site of a disused cement works have been unveiled.

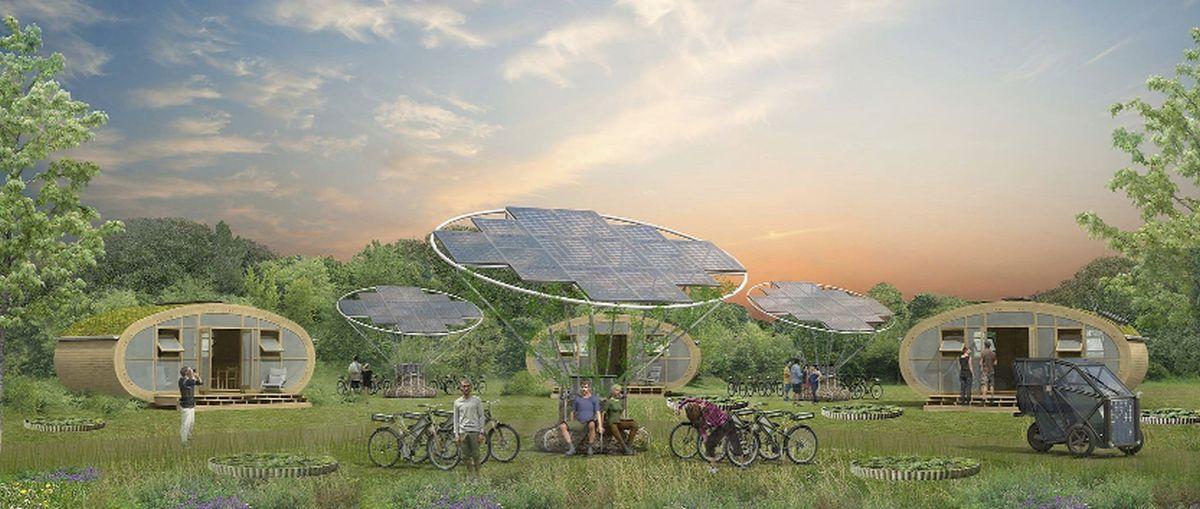

The proposal for the Off-Grid project includes 600 pods for holiday lets on the 118 acre cement works site at Upper Beeding.

The eye-catching project would retain the works’ main building, converting its roof into a ceiling of translucent solar panels capable of generating five megawatts of energy to power the holiday resort.

An outdoor amphitheatre set on an island capable of hosting live performances or large-scale screenings is also included in the plans, which the proposers hope to realise within five years.

It is estimated the redevelopment of one of the biggest brownfield sites in the South East could create 500 jobs when in operation and up to 700 jobs during construction.

The green project will vie with plans for major housing developments of up to 2000 homes for the future use of the site, which sits within the South Downs National Park.

It is the latest of a number of projects proposed for the giant industrial site, which closed as a cement works in 1991.

The site was purchased by Hargreaves in 1997 and the Sussex-based developers currently let the site to a number of businesses employing up to 150 people.

Aggregate suppliers Dudman are believed to have first option on the site.

The Argus understands three separate projects are vying to develop the site.

Off-Grid team member Alex Hole, who has overseen the eco-renovation of the former Mermaid Cafe beachfront building in Lancing, described Off-Grid as an “Eden Project within the South Downs”.

He said: “It would be really easy just to put housing on the site and that makes the most financial sense.

“But the South Downs National Park policy framework is that anything built in the park should only be allowed because it couldn’t be built anywhere else.

“Even if you make them all affordable homes, it’s not critical it would be built in the park.”

The plans have been drawn up by award-winning architects ZEDfactory and also have the backing of the Low Carbon Trust.

The holiday pods would range from studios to five-bed holiday homes, a luxury eco hotel with conference centre and hanging pods set in the quarry landscape.

Leisure attractions would include natural swimming ponds alongside a kayak, watersports and outdoor recreation venue, cable powered wake boarding, rock climbing, high rope centre and mountain biking all set into the quarry landscape.

In the retained factory building, Mr Hole said cafes and restaurant could operate all year round while a central auditorium could host small-scale music festivals.

Roof solar panels will allow the entire resort to be off-grid, while the camp’s water supply will come from a rainwater reservoir.

He said: “It’s a strange structure, not exactly attractive but people do enjoy it.

“It is a very solid structure and very difficult to knock down, which would have a large carbon impact so it’s actually much more efficient to adapt it.”

Mr Downs said he had been in contact with all parties connected to the site about the community-led proposals.

He said he had also held talks with two potential investors.

He said there would also be the opportunity for other investors through a share scheme.

A South Downs National Park authority spokeswoman said: “This is an important strategic site in a very sensitive location.

“We know that there are several different proposals in the pipeline, including a very exciting one from the local community.

“No applications have yet been submitted and there’s still much work to do to ensure that any proposals safeguard the South Downs’ wildlife, landscapes and heritage and can actually be delivered.”

The spokeswoman added that the site had the potential to make “a substantial contribution towards sustainable growth” but was not considered suitable for general market housing.

The plans for the site will be put forward for consultation as part of the Local Plan in September which residents will then be able to comment on.

Industrial monument or a blot on the landscape?

Analysis by Neil Vowles

TO COUNTRYSIDE lovers, the old cement works near Upper Beeding is a dark, forbidding blot on the landscape.

But to others, the grand old building is a concrete cathedral, a monument to industrial power now long gone.

Either way, the giant plant sprang up from humble beginnings.

A chalk pit existed on the site from at least 1725, and probably long before.

Lime burning had been carried out throughout the country for many hundreds of years, but took off in Shoreham during the industrial revolution.

Coal and clay was then shipped into the town and onwards upriver in barges to the quarry kilns.

The kilns were manned by skilled workers who watched closely as the burning chalk turned to lime over many hours, sometimes days.

A mixture of chalk and clay was also burned to make cement for building work.

During the 19th century, demand for cement boomed.

At that time, Shoreham had its own ‘cement house’ and ‘cement mill’ as the chalk from Beeding Hill was found to be of good quality.

The early years of the twentieth century saw the works grow considerably in size when new buildings and chimneys were built on the west side of the road.

As the cliff face was gradually ground back, away from the kilns, a tramway was built to convey the chalk for processing.

Company bosses chose to use manpower to push the trucks, although the 1901 records show one trolley boy called Edward Terry, aged just 13.

When the Sussex Portland Cement Company directors decided to expand the plant, they looked abroad for inspiration.

A similar project had just been completed in Demark, so Danish experts were sent for to help plan and build the giant works.

American-designed rotary kilns soon meant cement could be completely manufactured in two and a half hours, compared with ten days or more using traditional methods.

The kilns had their own fleet of barges to receive coal, coke and clay and send the lime and cement.

Soon, railway sidings were laid down to allow faster and more economical transportation of cement and materials.

With an efficient gang of men, 260 tons could be loaded in one hour, and as a result, output increased from around 5,200 tons in 1897 to 41,600 a year by 1902.

The booming business required more workers, who needed to be housed nearby.

Work on Dacre Gardens, the terrace of houses just north of the cement works, began in around 1901.

Later that year, 28 employees are recorded as living there with their families in the 14 new homes.

Space was tight, with up to 14 people crammed into just one house.

After the Second World War, and under the new name Blue Circle, the plant was completely rebuilt from 1948 to 1950.

During the 20th century Shoreham cement was used in huge quantities for many major construction projects all over the UK.

By 1981, the plant employed 330 staff and was producing a quarter of a million tons of cement a year.

But by the end of the decade, the site was deemed obsolete and after it had eaten away the whole hillside, the works finally closed down in 1991.

The site’s owners had never been placed under any obligation to demolish the buildings or restore the landscape to its original natural state.

Instead, production was simply halted, leaving the towering structures disused and empty.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel