ON May 8 1945 church bells rang out across England as the war weary population took to the streets for the party of a lifetime.

Victory in Europe had been secured – Hitler had been defeated.

But for thousands of British troops stationed many miles away in the Far East, this victory meant very little.

They continued to endure the heat, the disease and the brutal treatment dished out by the Japanese.

For those back at home, such was the relief at the end of the Third Reich, the brave men out in the likes of Burma, Malaysia, Java and Singapore, were all but forgotten.

It was only on August 15 1945, after the Americans had dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and later Nagasaki, that the Japanese finally raised the white flag.

Thousands had lost their lives and those who survived were changed forever.

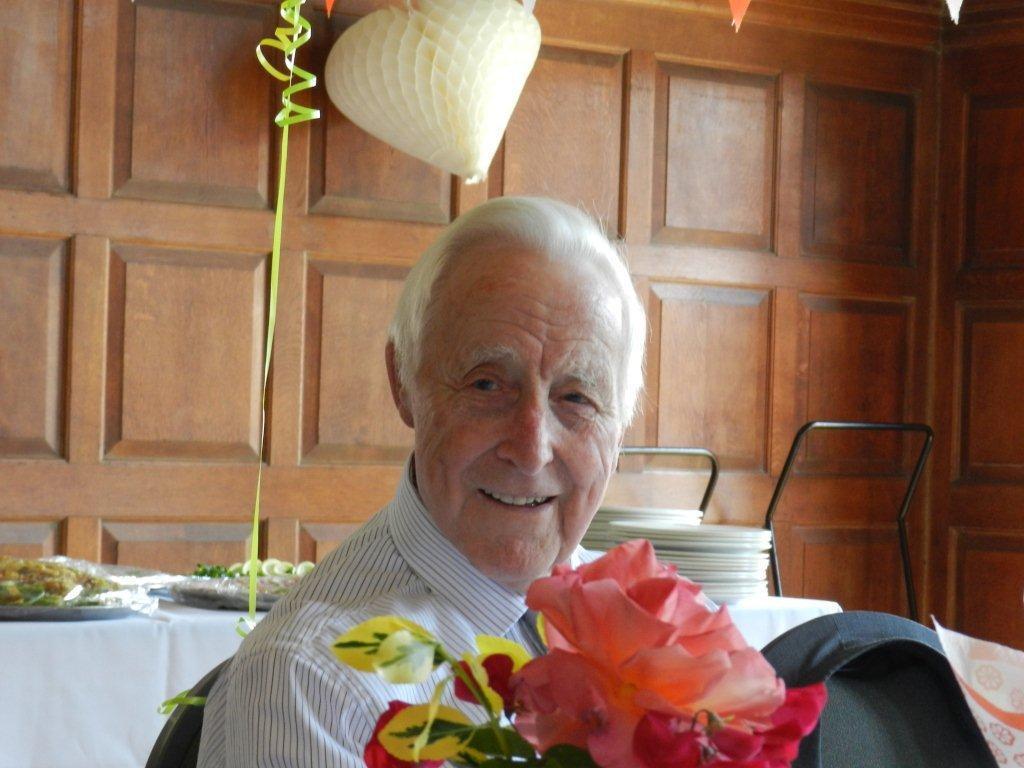

For Bob Morrell, a fitter in the RAF, his war years in the Far East still haunt him today through paralysing flashbacks.

He said: "I can be walking along Hove seafront when they come out of nowhere. They are terrifying. They only last a few seconds, but in those seconds I can see so much. They are real. I’m there, I’m back in the Far East.

"Part of me knows I’m not because I’m thinking, ‘grab onto that railing’, but I’m there, I’m back there.”

Bob, now 94 and living just off Lewes Road, Brighton, served in both the Battle of France and the Battle of Britain, working on a squadron of Hurricanes.

In 1941 he was posted to the Far East, but was captured by the Japanese in Java in March 1943.

Thousands of Allied prisoners died at the hands of the Japanese in squalid camps across the region. Conditions and sanitation were awful, food and medical care were almost none existent and the brutality of the guards reduced brave men to nervous wrecks.

Bob remembers all too clearly the moment he was captured as if it were yesterday. He said: “You were scared. Any man who said he was not scared was a liar, you just suppressed it. We really didn’t know what was going to happen. But if we had known then how we were going to starve, how we were going to be beaten and how we were going to die, I think every one of us would have shot himself instead of being taken prisoner.”

After being put to work on the docks in Java he was crammed into one of the infamous Japanese Hell Ships with 2,000 others and sent to the island of Haroekoe.

Men died by the dozen as they baked in the searing heat with little food or water. After 17 agonising days, they finally reached their destination.

Their camp was infested with maggots and lice and the men were rationed small portions of rice and little else. But they were not only expected to survive, they also had to work.

He added: “They wanted us to build an airstrip across two hills. We were working on coral and we were chipping away at it with six inch chisels and a hammer.

“They didn’t see us as human beings, we were slaves. To this day I just don’t understand their mentality. If they wanted the job done, they could have treated us well, fed us, looked after us and we would have done it well and done it quick. But they didn’t, we worked dawn until dusk, with little food, no medicine and they beat us.”

Of the 2,000 that made the journey to the island, around 600 died in the 18 months they were there.

He added: “When I came back from a day’s work, they would look at me and gesture at the bodies. I would have to carry the coffins over to the pit. I just wanted to collapse and sleep, but I had to carry 10, sometimes 12 coffins at the end of a long day. It’s hard to think of now, but war does funny things to your mind. I resented them dying. I thought to myself ‘I’ve had enough and now I’ve got to carry you over there’. It’s not ‘poor old Bill’, it’s ‘why did he have to bloody die on my bloody shift’”.

A year and a half after arriving they were crammed onto another ship and sent back to Java. In the same squalid conditions with little food and water, the men were at sea for 67 days. Of the 630 to board the ship, just 325 survived.

Bob was one of them. Just.

Barely conscious, he was carried from the ship by his friends and rushed to hospital as he slipped in and out of consciousness.

Nobody expected him to survive, but remarkably he did and after many months learning how to walk again he was returned to a Japanese POW camp.

Victory in Europe had been and gone, but it had made no difference to Bob and his friends.

However, the events of August 6, 1945, did.

The Americans had dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima and within days the guards started to disappear. Days later the war was over.

After four long years, Bob arrived home. Brighton was a city unchanged, but what he had experienced had changed him irreversibly.

He returned to his home in Brunswick Mews without fuss and got on with his life. Bob is one of thousands of forgotten heroes who sacrificed everything for the freedom we enjoy today.

He will be reading the Kohima Epitaph at the Easthill Park (Portslade) commemoration service on Sunday.

The main commemorative event for Brighton and Hove will be held at Easthill Park War Memorial, Manor Road, Portslade.

The service, which has been organised by the Java Far East Prisoners of War Club and Portslade Royal British Legion, will begin at 2.45pm.

Guests are urged to gather at 2.30pm.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here