John Napier: Stages, Beyond The Fourth Wall

Towner, Devonshire Park, Carlisle Road, Eastbourne, Sunday, November 29, to Thursday, January 31

DESIGNER John Napier is keen not to call his debut Eastbourne show a retrospective.

“It’s a homage to having the best time ever,” he says from his studio near Seven Sisters. “I was a working class boy from Tottenham with zero ambition and little expectations. The only thing I was ever told was I needed to be about to provide for a family and needed to get a job.”

Napier’s chosen career in stage design saw him revolutionise what could be done on stage – from tearing up the stage in the Royal Court production Big Wolf so the audience had to climb over rubble to get to their seats, to creating a roller-skating train track which went out into and around the audience for Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Starlight Express.

His design for Miss Saigon – which saw a helicopter land onstage during a crucial scene – is often cited as the apex of the West End stage blockbuster in the 1980s and early 1990s.

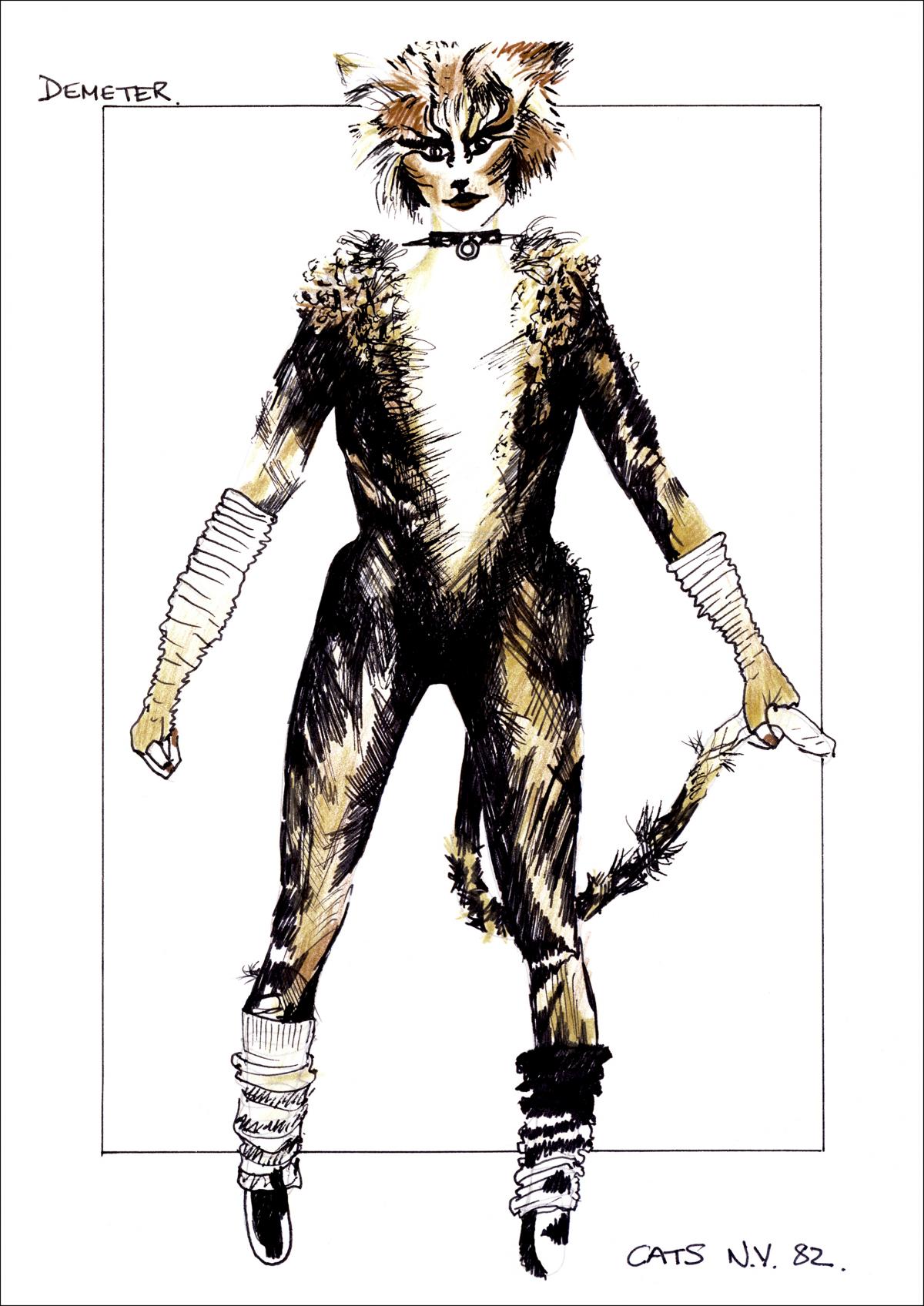

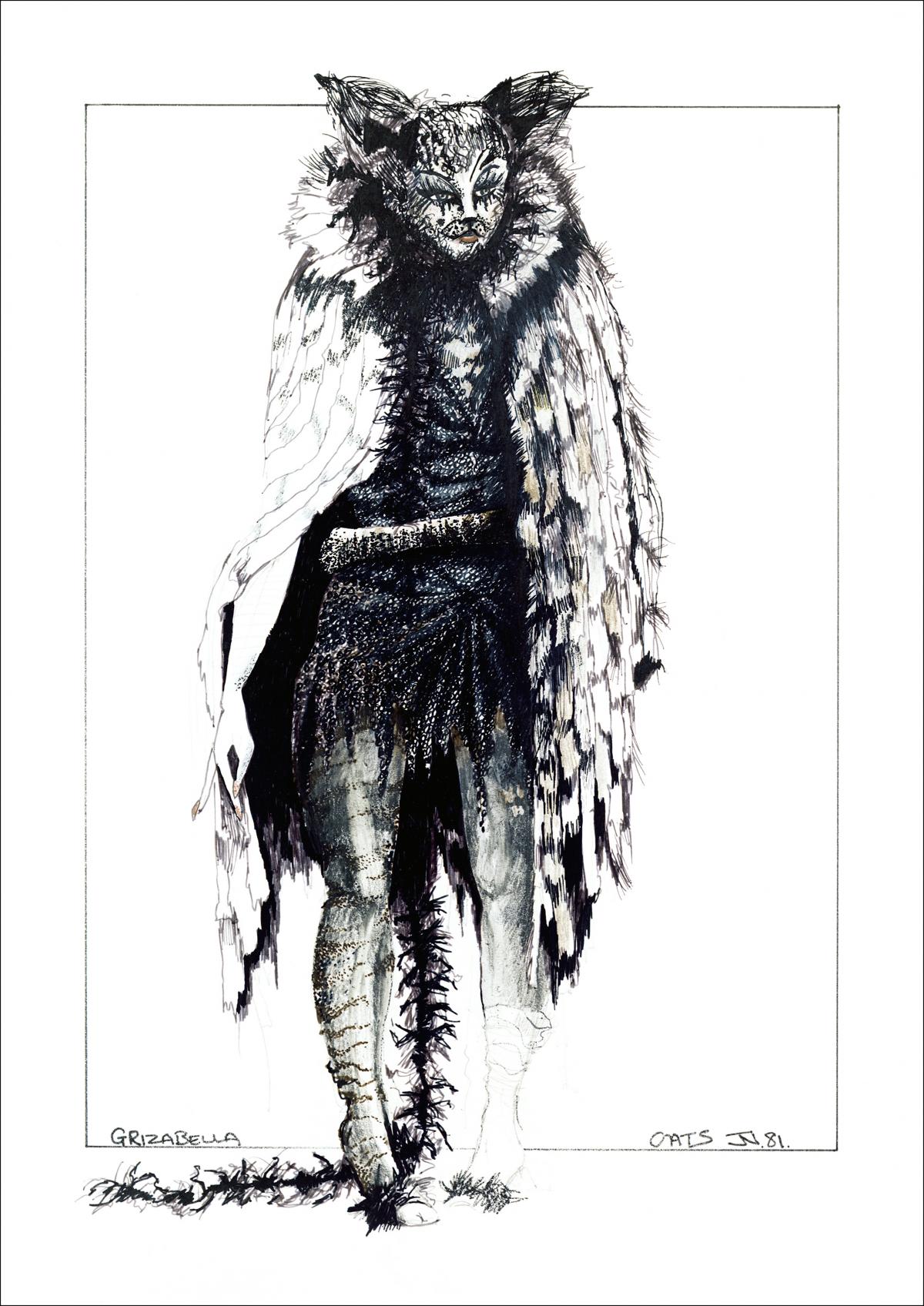

But his CV also includes the original designs for classic musicals Cats, Jesus Christ Superstar, Les Miserables, and Sunset Boulevard.

He has been associate designer with the Royal Shakespeare Company, created productions for the Royal National Theatre, Glyndebourne and the Royal Opera House, as well as working with Steven Spielberg on the cinema blockbuster Hook, Michael Jackson on his Captain EO video for Disney and magicians Siegfried and Roy for their Las Vegas show at the Mirage.

But with Stages, Beyond The Fourth Wall he is going back to his first love, sculpture, taking inspiration from his extensive theatrical career.

“They are relatively abstract sculptural pieces that have taken their beginnings from my theatre work,” he says, adding he didn’t want to put together a display of theatrical set models and original drawings.

“I have tried to mount an exhibition that’s a bit more dynamic. I’m trying to take pieces and transform them into objects that stand alone.”

So Cats and Les Miserables combine models from the stage sets with production photographs. Other pieces, such as Equus, or Bond’s Lear, are about creating arresting images to capture a sense of the finished production in one image.

There is also room for some more abstract pieces inspired by Napier’s interest in anthropology – such as the brutal looking circle of blades that makes up No More Hunter Gatherers.

Most of the images have never been displayed in public before.

In working with sculpture Napier is going back to where it all started, as a student at Hornsey College Of Art.

“At school I was a hopelessly dyslexic kid,” says Napier. “I could easily have just become factory fodder at my secondary modern school.”

It was a visionary art teacher who was able to change things. Napier found out, at the age of 45, that the teacher he knew as Mr Birchall had gone out of his way to see his parents and encourage them to send their son to art school.

“He told them: ‘John has to go to art school because in all my years of teaching he’s the most imaginative boy I have ever had in my class’,” says Napier, who includes another quote from his Parkhurst Secondary Modern teacher on his website: “If John does not go to art school, I would have wasted thirty years of teaching”.

“He said if my imagination carried on through into my adult life in the same way I could have a career in the arts. My parents thought of the arts in terms of the Charlie Chaplin style tramp, living in a garret, eating the sole of his leather shoes – they thought they were always poor and destitute.”

They encouraged their son to investigate graphic design with a view to getting him a job in advertising – but Napier found inspiration in sculpture and ceramics.

It was regular trips to the Royal Court, Sadlers Wells and the Royal Opera House which helped him see where his love of sculpture could take him.

“I remember going to see Beckett, Pinter and Arnold Wesker plays at the Royal Court,” he says. “But the most important one for me was going to see David Hockney’s designs for Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi. I remember sitting there mesmerised – it was like a series of paintings come to life.

“There was more to theatre than Agatha Christie and picking out the right sofa for people to sit on.”

He gained more inspiration from contemporary dance, including Martha Graham and Pina Bausch’s later work.

“It’s like poetry with the human body,” he says. “It doesn’t have to have a structure that makes complete narrative sense. You revel in it - it touches some part of your mind and your spinal cord in a way conventional story-telling doesn’t. There’s something primeval about it.”

His starting point for every theatre production has always been beginning with a blank page and a copy of the script.

“I try not to have a style,” he says. “I’m primarily servicing the company, or the play or the musical.”

Following his famous Miss Saigon stage designs Napier says director Nicholas Hynter described him as “the purveyor of mechanical garbage”.

And to some extent junk is a regular feature in his work – from his revolutionary designs for Big Wolf in 1972, capturing the aftermath of a plane crash in the Royal Court Theatre, to the junkyard at the heart of Cats and the barricades of Les Miserables.

But he admits he was a little disheartened by the reaction to his Miss Saigon helicopter.

“It was something I was asked to supply,” he says.

“As designers our job is to service the production – if we’re asked to build something we do it. The public relished it – so I got a bit of a reputation for doing things that were hugely mechanical.

“The director wanted the helicopter to be the most real thing in the production – that it must look like a documentary, and so that’s what I did. People at Drury Lane Theatre remarked on how extraordinary it seemed to have a helicopter land on stage. Great exception was taken by various people connected to the production, I suspect because it got all the headlines.

“In our everyday lives we use mechanical things – most of us get into a car to drive somewhere, or go on a train or an aeroplane, or watch a JCB digger working on the road and think no more about it. But when you put it on a stage the piece of machinery can change the space. You get castigated for it!”

His set for Sunset Boulevard couldn’t have been further from the junkyard aesthetic though. Napier took inspiration from Billy Wilder films to create something akin to a cinema set where Gloria Swanson could dominate – with a giant winding staircase at the centre of proceedings.

His Sunset Boulevard piece has a model of the same staircase at the centre, surrounded by images of the production topped by the infamous swimming pool which starts the story.

“[Theatre director] Terry Hands said to me that people remember a photographic image of productions in their mind,” he says. “Most people wouldn’t be able to quote the words of the play, but the images from the productions stay in their brains.”

At the height of his career in 1990 Napier was travelling from LA to work on Spielberg’s Hook, to London for the stage premiere of Children Of Eden and the Broadway transfer of Miss Saigon.

“I was doing that for something like three and a half months,” he says. “It’s hard to be creative in that situation. I was thankful when Children Of Eden opened in London and I only had to travel across America for the next three months!”

To go alongside his artistic distillations of his design productions is a cabinet of bits and pieces featuring items and drawings from various shows that wouldn’t necessarily make sense on their own.

In some ways his exhibition captures a world of the past, as today most designers provide concept boards and computer models rather than physical models.

He is still trying to keep his hand in with theatre – returning to the Royal Court in 2009/2010 for Anupana Chandrasekher’s play Disconnect to help mark the theatre’s 40th anniversary.

“People think I’m too rich and too old, immersed in large scale productions,” he laughs.

“I’ve spent four decades working with some of the top playwrights in the world, and professionals in the film world, and doing major productions in Las Vegas. It doesn’t come any better – you get to see every bit of the kaleidoscope. I haven’t got stuck in a niche which happens to a lot of people. I think I would have got bored if I’d stayed at the National Theatre for 25 years.”

For now he is enjoying working in his studio by the sea, where he moved at the middle of last year.

“I’m at the age now where I do what I want to do and don’t care what the outcome is,” he says. “This exhibition isn’t about ego, it’s about wanting to do something that has some life behind it.”

Open Tues to Sun and bank holidays 10am to 5pm, tickets £5/£3.50. Call 01323 434670 or visit www.townereastbourne.org.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here