IT IS hard now to imagine the sight of German soldiers landing on the pier, charging up the beaches, marauding over the South Downs or pillaging our villages.

Yet, in the face of an imminent Allied defeat in Dunkirk and possible invasion by the Nazis, this is exactly what was on everyone's mind as the Second World War unfolded.

In May 1940, only days before the evacuation of British forces from France, the Government officially recognised a growing body of men who, if needs be, were ready to fight for their country in their own back yard.

Aged between 17 and 65, they would be called Local Defence Volunteers and then renamed the Home Guard.

The initial response was overwhelming; 250,000 volunteers, many of whom had seen action in the First World War, signed up in the first week.

One of the younger ones was Adrian Montford.

The 92-year-old, who lives in Brighton, joined aged 17 before he was conscripted into the regular Army.

He told The Argus: "Most of the blokes were older and they had all been through a war and felt they could do as good as job as anybody else. I respected them.

"There was a funny mix of people - we had all sorts and that was the nice thing about it. They came from all parts of society but they got on well."

Mr Montford was with a unit in Surrey for a year before fighting in Africa, Italy and Greece with the Army.

He said the Home Guard was far removed from the image of Dad's Army: "We spent most of the time playing four-card brag.

"I didn't think the training was terribly good, actually. We went down to the seafront and fired some live rounds once. But other than that we didn't do any shooting.

"We had sticky bombs to stick on to tank tracks to blow them up and mostly we used to do things like stop people looting damaged shops after they had been bombed.

"It was dull compared with Dad's Army. It would have been a lot more fun if it had been similar."

On a more serious note, with the benefit of hindsight, he did not think the Home Guard would have withstood a German invasion.

He said: "I was quite convinced that I was going to sit in a hedge, shoot one German and that would be my lot.

"On the South Coast, it was pretty obvious they weren't going to be stopped there. If there was a real invasion I don't think any of us would have lasted very long. We would have put on a good show for the first wave but when you're young you don't think about that."

Denise Bennett, now living in Portslade, saw the Home Guard patrolling around Brighton as a child.

The 87-year-old concurred: "At one stage, if the Germans had come over, they would have walked right through. We wouldn't have survived.

"We realised a lot of the Home Guard only had pitchforks in the countryside.

"A lot of them were very efficient but there were other units very similar to Dad's Army.

"Mind you, they did some very good work, too. When the bombs dropped, they helped along with everyone else.

"And they were very strict about carrying ID around with you. If you didn't have your ID or your gas mask with you, you got into trouble."

Mrs Bennett remembers Home Guardsmen meeting on Varndean fields in Brighton and in the copse where Dorothy Stringer school is now for training.

Other training areas in Brighton included sites in Circus Street and at Preston Circus Fire Station.

The Home Guard itself, as it expanded, needed separate headquarters. Clerks at the Army Hall in Gloucester Road were kept busy signing up new members. Meanwhile, Brighton Station was also signing up members for Southern Railway, needed to guard important railway installations on the line.

Mrs Bennett said: "I think everybody wanted to do their bit. It didn't matter what age you were.”

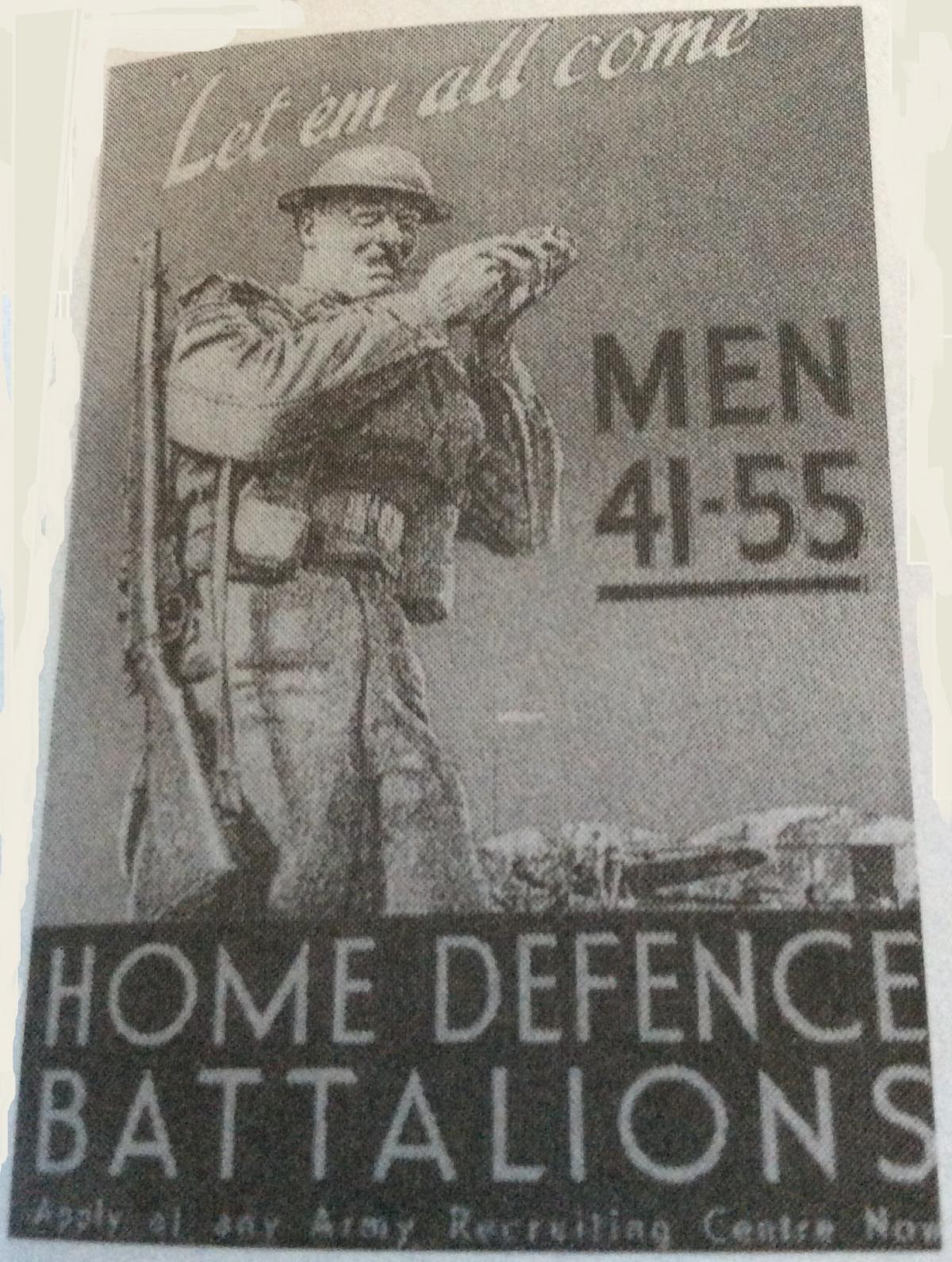

In Brighton there was initially a shortage of volunteers for the Home Guard and mayor J Talbot Nansen headed an appeal, issuing a poster.

Some were a bit too enthusiastic.

Mrs Bennett added: "Some of them were very officious and enjoyed acting up to the role.

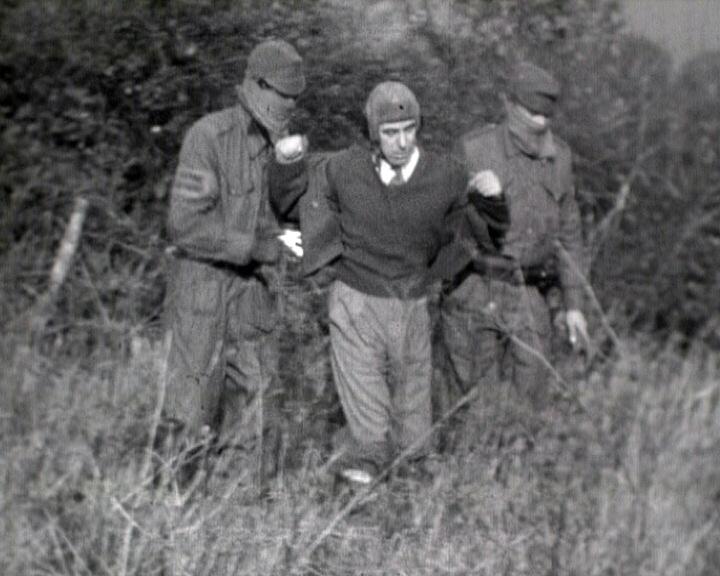

“Some of the worst situations came when the Polish pilots were shot down by the Germans. The Poles were on our side but because they couldn't speak English the locals thought they were German.”

She recalled how “one poor man” did get killed by an over-anxious Home Guard group near Hurstpierpoint. Most units would wait for the RAF to come along and confirm pilots.

But with an aggressive streak, could the Home Guard be mistaken for the Army?

Historian David Rowland, who has written books on the war such as Brighton Blitz and Target Brighton, thinks so.

He said: "As a young boy living in Brighton throughout the war, I remember seeing the Home Guard but I didn't know they were the Home Guard. I thought they were members of the regular Army. I couldn't understand why they were not abroad fighting the war. I saw them around guarding various places such as the gasworks at Black Rock and in Hove.

"It made you feel safe to see soldiers about with guns. In reality, they would have done their best but would they have saved us if Germany had invaded? I'm afraid not.”

Alan Dart, now 79, was a young boy while the war progressed and, occasionally spending time with the Home Guard, saw it as a big adventure.

After being bombed out of his home in London, his family moved to Brighton in 1940.

His father was in the Home Guard as well as serving with a detachment of the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers.

Mr Dart sometimes rode in the van used by a Home Guard unit at Moore's Garage in Russell Square, Brighton.

Much like Corporal Jones's butcher van in Dad's Army, it did not resemble a military vehicle, instead painted sky blue with big chrome letters on it.

Now living in Holland Road, Hove, Mr Dart remembered: "It was quite exciting riding around in it. We were only kids but they let us hang around with them. It seems strange now, really.”

Mr Dart recalls a shooting range near St Wulfrun’s Church in Ovingdean and used to sneak ammunition from it with his friends to make fireworks.

Mr Dart also remembers seeing early units dressed in denim outfits, equipped with only wooden rifles before getting the proper kit. “I used to laugh but that’s all they had,” he added.

Despite its inauspicious beginnings, by the end of the war, more than 1.7 million men and 31,000 women who served in the Home Guard were awarded a certificate signed by King George VI.

Mr Rowland added: "The members of the Home Guard should be applauded for their volunteer work. Full marks to each and every one of them."

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel