IT has been standing for around 130 years and has recently survived plans to chop it down.

Only a few years ago, the elm tree at Brighton’s Seven Dials roundabout was due to be felled by Brighton and Hove City Council as part of roundabout improvements but following overwhelming public pressure, as well as protests involving activists camping in the tree, the council decided to save it.

Now the beloved tree is in the running for the Woodland Trust’s Tree of the Year award, up against the sycamore that starred in the movie Robin Hood: Prince Of Thieves, the original Bramley apple tree in Nottinghamshire and an 800-year-old oak in Wales.

If estimates of the elm’s age at around 130 years old are correct, the tree would have put its roots down by the 1880s when Victorian Brighton was booming, tourists were flooding in and places for pleasure and leisure to entertain them were appearing everywhere.

Transformed after the 1730s from a “forlorn town” into a fashionable seaside destination thanks to the current fad for drinking and bathing in seawater for health benefits, the town attracted the patronage of the Prince Regent, who visited to try its waters himself.

He, of course, went on to build his exotic pleasure palace the Royal Pavilion, and as his presence in Brighton attracted more and more people, new grand buildings began to spring up and Brighton, once a marshy featureless desolation, began to become visibly more attractive. In the 1700s, the town had few trees, prompting the author Samuel Johnson, a frequent visitor to Brighton in the 1770s and a lover of trees, to comment that “the place is truly desolate and if one had a mind to hang oneself for desperation at being obliged to live there, it would be difficult to find a tree on which to fasten a rope”.

But by the 1820s, thousands of trees including hundreds of elms, were planted in and around Brighton, encouraged by a £300 donation from the prince himself.

With the prince’s presence giving Brighton the royal seal of approval, expansion of the town was inevitable. In the 1820s, the architects Thomas Kemp and Charles Augustin Busby had begun developing Brunswick Town and Kemp Town in Brighton, and part of the Clifton Hill area, between Vernon Terrace and Dyke Road, was also in its earliest stages, the earliest Victorian residential development in Brighton where much of the housing considered high class.

By contrast, Seven Dials, located on a hilltop ridge and named after the seven roads that radiate out from its centre - Dyke Road (twice), Buckingham Place, Chatham Place, Goldsmid Road, Prestonville Road and Vernon Terrace - was still home to market gardens, windmills, brickfields and an open-air laundry run by a Mrs Watts.

However, the opening of the railway in Brighton in 1841 began the slow change of its character and new terraces and villas as well as pine trees began to replace the brickyards and the windmills. On the site of a cricket ground, Montpelier Crescent, a magnificent crescent of houses, some with giant fluted pilasters and Corinthian or ammonite capitals, designed by Amon Henry Wilds, was being developed, while houses were constructed close to St Ann’s Well, creating Goldsmid Road, which was named after banker and financier Sir Isaac Lyon Goldsmid.

In the 1850s Vernon Terrace, off Seven Dials, an impressive terrace of 37 houses with ironwork balconies, was built, and a decade later the Prestonville area, including Prestonville Road, was developed by Daniel Friend as a middle-class housing estate.

There were new grammar schools and parks by the 1880s, when the famous elm took root, and Seven Dials was linked to the rest of the town by a horse bus network.

By the 1880s, Brighton no longer had a royal presence. Queen Victoria was not amused by Brighton and refused to live in the Royal Pavilion because “the people here are very indiscreet and troublesome”. She sold it to the town after stripping it of its furnishings, and it still attracted eminent visitors including the King of the Belgians in 1867, Emperor Napoleon III of France in 1872, the Emperor of Brazil in 1877 and the Shah of Persia in 1889.

And despite Victoria’s continued absence, day trippers were pouring in to Brighton, largely thanks to its rail connection to London. The West Pier and the Chain Pier (which would be swept away in a storm in 1896) drew in the crowds and by the end of the 19th century, Brighton would also have the Palace Pier, when the cliffs to its east would be developed into a walled esplanade with terraces and wrought iron arcades designed along the lines of the Royal Pavilion as well as the mile-long strip of tarmac laid as a motor racing track and known as Madeira Drive.

The great and the good also flocked to Brighton, staying in its impressive seafront hotels such as the Grand hotel, the Bedford Hotel and the Metropole Hotel.

The eight-storey Italian-style Grand hotel, built in 1862-4 at a cost of about £100,000, was the tallest building in Brighton and was one of the first hotels in the country to include electric lighting and 'ascending omnibuses' – or lifts, as they would later be called.

Guests at the Bedford Hotel, where royalty and the aristocracy stayed, included George IV’s sister, Mary Duchess of Gloucester, and his brother the Duke of Cambridge, the Duchess of Teck, Princess Lieven and Prince Metternich, King Louis-Philippe and Emperor Napoleon III, Lord Palmerston, Victorian novelist William Makepeace Thackeray and Swedish opera singer Jenny Lind.

And the town also had many illustrious residents. In the 1880s, the town was home to Juan, Count of Montizón, the Carlist claimant to the throne of Spain and Legitimist claimant to the throne of France, who lived in Hove until his death in 1887, and British Indian businessman and philanthropist Sir Albert Abdullah David Sassoon, who died in Brighton in 1896 and was buried in the Sassoon Mausoleum, which he had had built in St George’s Road.

The Irish nationalist politician Charles Stewart Parnell died at his home in Walsingham Terrace, Hove, in 1891 aged 45, and Brighton was the birthplace of trade union pioneer Clementina Black, who lived in the town until the 1880s. She was close friends with Eleanor Marx, the daughter of revolutionary socialist Karl Marx, who had lived in No 6 Vernon Terrace in the 1870s.

The naturalist and collector Edward Booth was also living in Brighton. Booth, who was born in Brighton, had a particular fascination for birds and aimed to collect examples of every bird species found in Britain, He founded the Booth Museum in Dyke Road, near to Seven Dials, the first museum in the country to present examples of species in Victorian-style dioramas and donated it to the town in 1890.

Magnus Volk, who built Brighton’s famous Volk’s Electric Railway, was also living in Brighton. After building the world's oldest extant electric railway, he introduced a three-wheeled electric carriage powered by an Immisch motor to Brighton in 1887, followed in 1888 with an electric four-wheeled carriage made to the order of the Sultan of Turkey.

Meanwhile, in Church Road, Hove, early film pioneer James A Williamson was creating his own home-made filming apparatus and beginning to make films, including the actuality Devil's Dyke Fun Fair for the Hove Camera Club's annual exhibition in 1896.

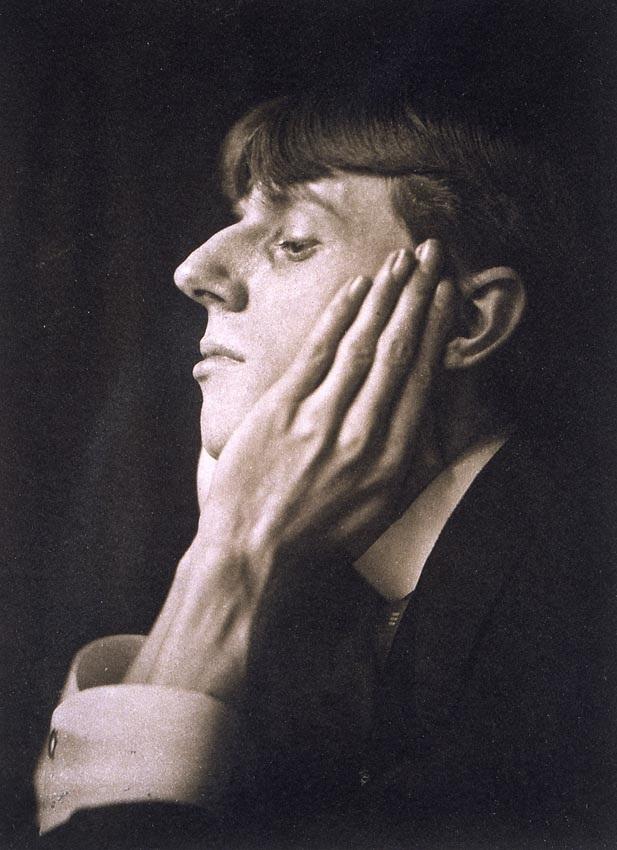

In the 1880s, the art nouveau illustrator Aubrey Beardsley, who was born in Buckingham Road, Brighton, was a pupil at Brighton, Hove and Sussex Grammar School. His first poems and drawings appeared in the school magazine. Famous for his erotic images, he was later advised to become a professional artist by the artist and designer Edward Burne-Jones, who at the time frequently visited the family’s holiday home, Prospect House in Rottingdean.

By the turn of the century, Brighton’s place as one of the country’s favourite seaside towns was firmly established, becoming one of England’s largest towns.

Today, it has thrown off a somewhat sleazy reputation it acquired in the mid-20th century that prompted the writer Keith Waterhouse to comment that “Brighton is a town that always looks as if it is helping police with their inquiries” to evolve into the country’s most bohemian of cities.

And that’s all thanks to its exotic architecture, creative characters and colourful history, a part of which is the Seven Dials elm tree.

• To vote for the Seven Dials elm in the Woodland Trust’s Tree of the Year award, visit woodlandtrust.org.uk/visiting-woods/tree-of-the-year.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel