I SOMETIMES wonder why I’m doing art when everyone is eating everyone else” says Ipek Duben. It’s a hyperbolic, rhetorical question from a socially conscious artist concerned about her role in a precarious world.

While her quote might suggest an element of doubt in her creative endeavours, though, it can hardly be said that Duben is immobilised by anxious self-examination. The opposite is true, in fact – Duben is using art to explore and present social issues in her homeland

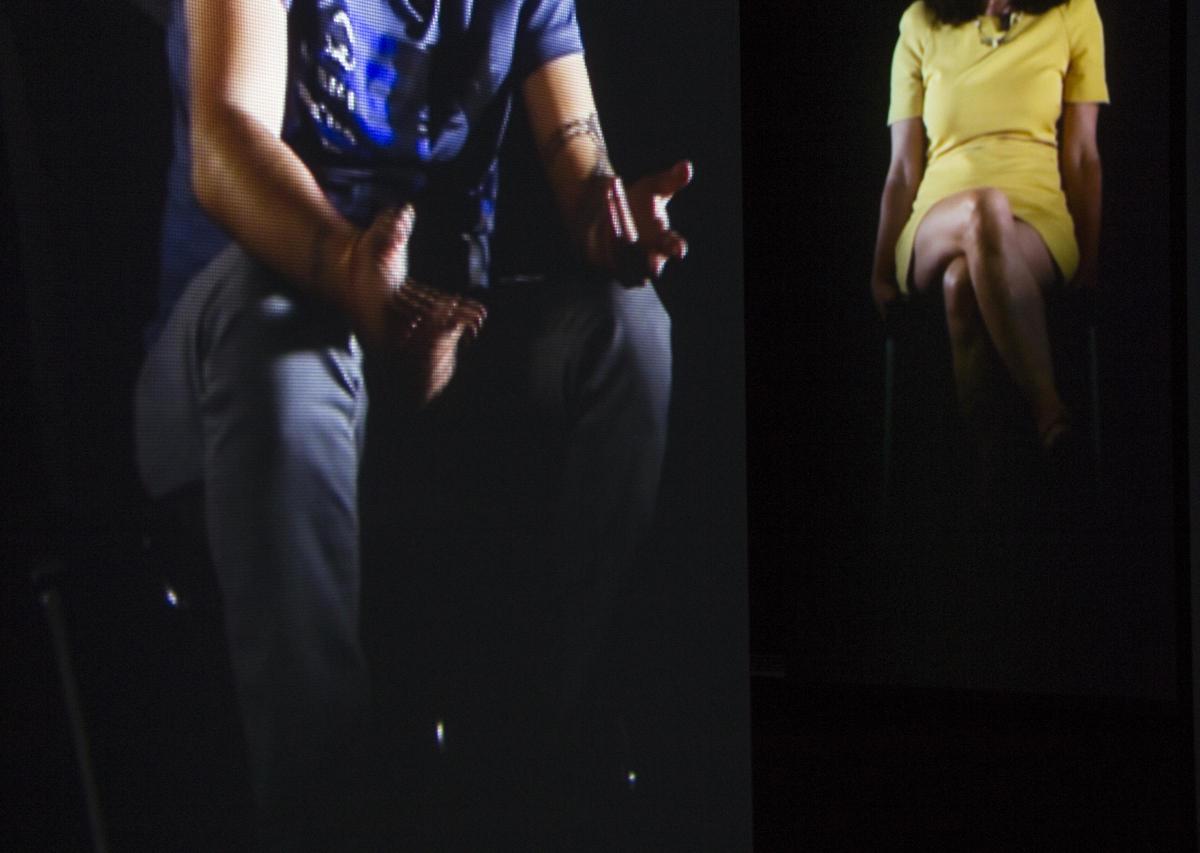

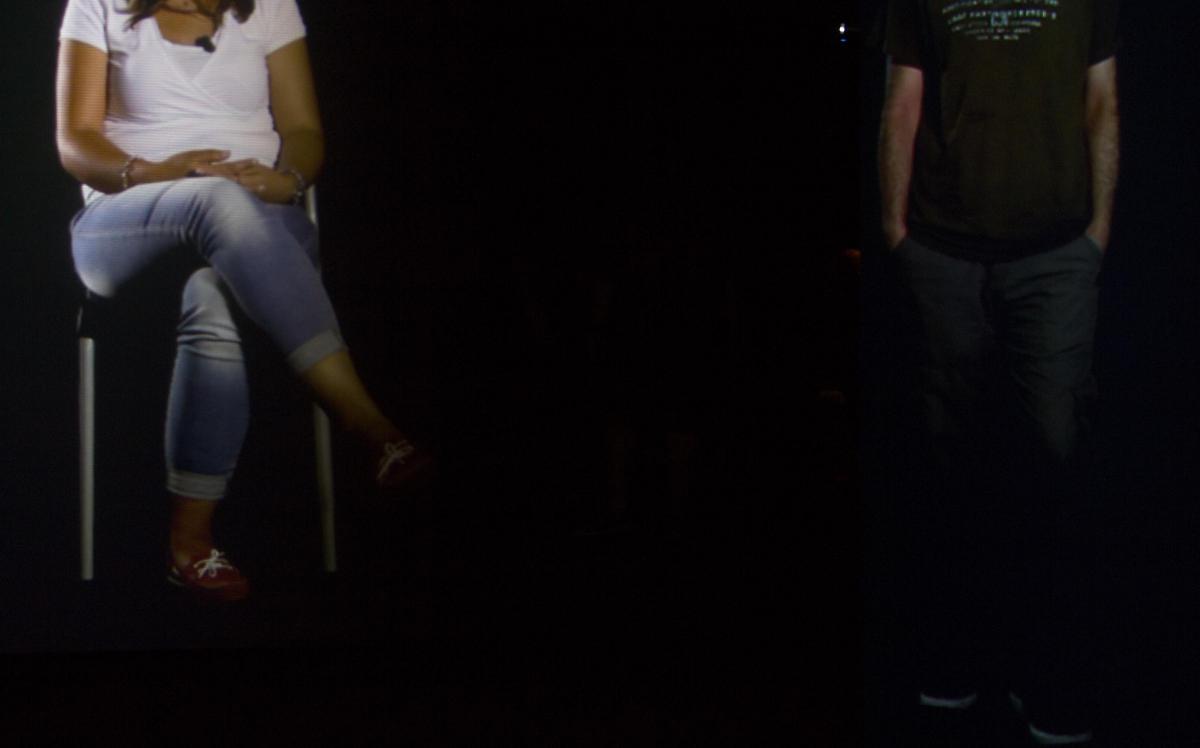

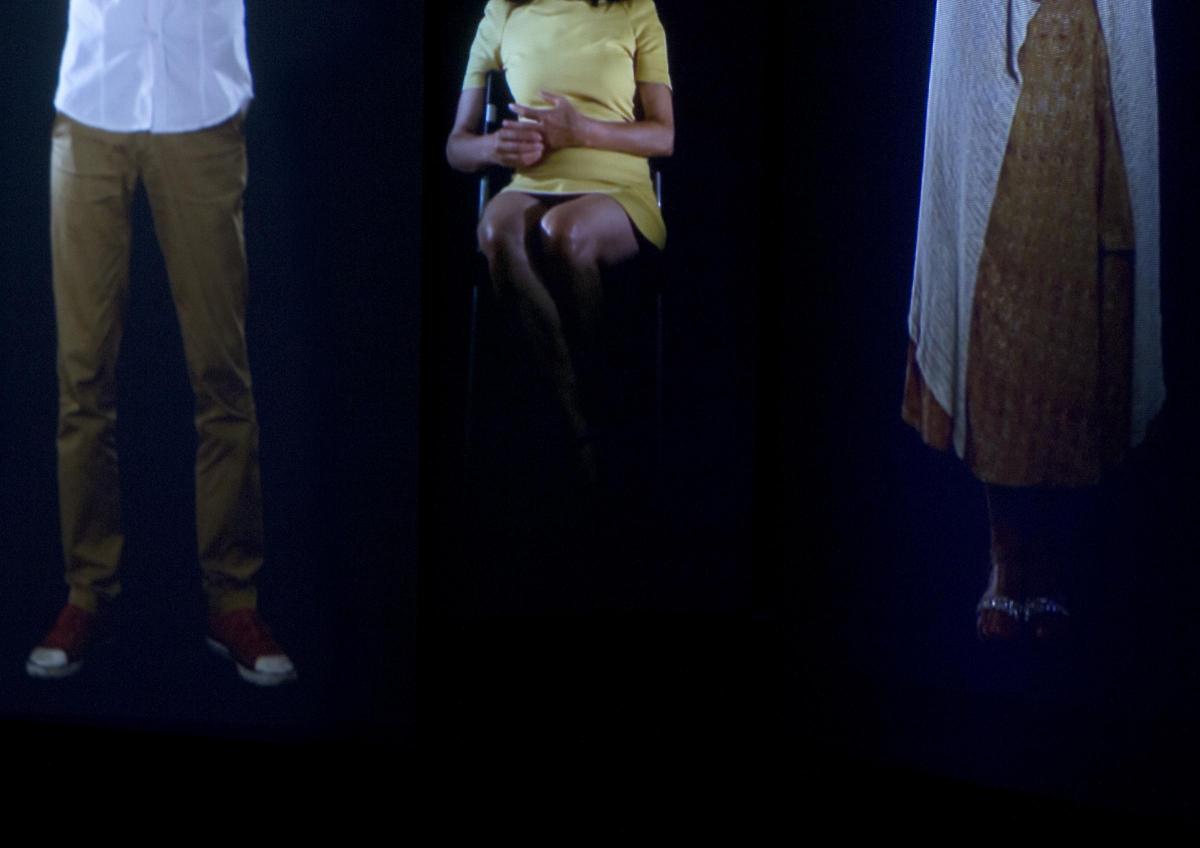

Her multi-screen installation They/Onlar, showing at Fabrica gallery in the weeks before and throughout Brighton Festival, focuses on marginalised and discriminated minorities in Turkey, from ethnic and religious groups such as Kurds, Armenians and Jews, to the LGBT community and women subjected to domestic violence.

She calls such people the “other’s other”, working on the premise that Turkish people are already classed as “the other” in the collective mind of the Western world. Duben worked hard to win the trust of such minorities before interviewing them. Their stories will be told via hanging screens and sound hubs at Fabrica in the UK premiere of the installation.

“I was very aware of the geographical specificity of the project,” says Duben. “Why should anybody here care how a Jew in Turkey feels, or an Armenian, or a Kurd? But the point is that discrimination is so widespread it’s like everybody is against everybody else. People in the West have had to realise they need to go beyond just cursing these people or killing them. Not everybody is a terrorist.

“I share Westerner’s views towards Islamic terrorists. I hate them. I can’t stand the Sharia Law. There are a lot of people that feel like that.” On the week after the Brighton Festival launch, and guest director Kate Tempest’s rallying call for empathy through the arts, They/Onlar feels highly pertinent.

Not to mention the fact that deep schisms in the UK and America were highlighted in such dramatic fashion last year, leaving many people to feel estranged among their compatriots. But, even with the best of intentions and an open mind, can Brighton audiences truly tap into the kind of marginalisation that Duben’s subjects speak of?

The artist says that visitors to Fabrica will be “horrified to hear some of the stories of suppressed women and gay men” [to name just two victimised groups].

“That’s a very good question and has been my concern all along. It depends on how universalistic people are here. I think it will create conflict in their mind. They would think of me as a Muslim, whatever that means. Duben, however, refuses to be identified as a Muslim artist or a female artist. “I am an artist, simply” she says.

The thematic narrative of the exhibition revolves around the idea of a “good citizen” in Turkey, a term coined by the marginalised – and particularly one Armenian man Duben spoke to – to describe the state’s notion of an exemplary Turkish person.

“The dominant ideology belongs to the Sunni men,” says the artist, referring to the majority denomination of Islam. Everyone else is discriminated against – some overtly, some covertly. The discrimination doesn’t go away. That’s true for Kurds and Armenians and Jews and so on – they lost their identity and, in a way, they disappear.”

As Duben talks about these people, it becomes more and more understandable why they might have reservations about giving themselves – and their stories – over to an unknown presence with a video camera [hence the concealment of their faces]. Duben had to tread a fine line between subtly earning her subjects’ trust and being bold enough to ask them personal, probing questions.

“It wasn’t easy because people don’t necessarily want to talk about histories and tragedies. Getting any gay person to come and talk to me was near impossible, for instance. I had a very hard time finding these people but I had to be direct. I went to meetings between certain groups, and I would tap on shoulders and ask people if they would like to participate in my project.”

While she was able to persuade a sizeable selection of people to talk in front of the camera, there was one minority group that is absent from Duben’s work. “There are no Greek-Turkish citizens in my piece because not one of them would participate. They must have come to an agreement among themselves that they were not participating in any Turkish project. That’s the one group I’m missing.”

In a previous project, under the self-explanatory yet complex title What is a Turk?, Duben attempted to unpack the Western definition of “The Turk”. She claims this characterisation has been prevalent in Western society for 500 years.

“I think my next project should be be Turks looking at the West – to see what they think about it,” she says, with a laugh, but it does seem the logical next step in her exploration of Turkish identity and the way it is interpreted around the world.

The artist is keen to stress that Turkish society is always changing [“you never know where you are”] and that there are more options available to women, for example, than ever before. She tells an anecdote from her childhood which illustrates both the cohabitation and segregation between Turkish-born people and minority groups.

“I went to school with Armenians and Jews and Italians and so on. I was in elementary school, walking on the street one day, when I heard to guys talking in a different language. At the time, the government was posting statements all over, like “Citizens – Speak Turkish”. I was only a kid at the time, so I turned around to these two guys and said “speak Turkish". Years later I realised they were Kurdish workers. At that age I didn’t even know they were Turkish citizens.”

Duben says she “never felt discrimination” in her 26 years living in America – “for being Muslim or a woman. But that was probably because I was a ‘good citizen’, I was very modernised and Westernised.

“My husband is Jewish and American and it made me realise that I come from a majority culture. The American Jews are a permanent minority. They carry that consciousness with them." The artist’s move back to Turkey has made her all the more aware of fundamental injustices and ideological differences between her homeland and the rest of Europe.

“It has been 40 years since Turkey applied for EU membership. In the last 15 years Turkish economy has exploded, way above that of Romania and Hungary, who joined the EU. “It has become crystal clear to the Turkish people that they would not be allowed entry to the EU because of religious differences and that the EU is a Christian club. There is no other reason in my mind for the exclusionary attitude of the West.”

Duben may be deeply worried about a number of global issues at the moment, most pressingly those of her own home country, but her work helps us to archive a greater understanding of the world we live in. It won’t be comfortable viewing, but it will certainly leave a deep impression.

If Duben herself says she was “very affected by what I learnt” from her subjects, the work will surely resonate with a wider audience. “I want the audience immerse themselves fully – to see something they don’t want to see and don’t want to know about.”

They/Onlar is showing at Fabrica gallery in Brighton from April 8 – May 29

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel