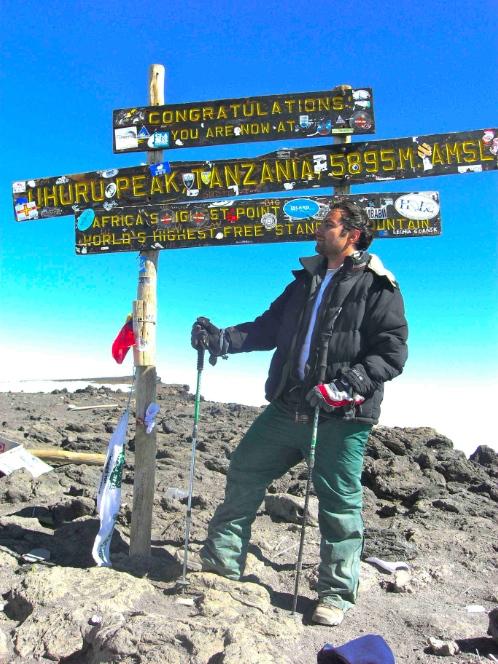

Last week an expedition of young mountaineers from the University of Sussex reached the summit of Mount Kilimanjaro, the highest peak in Africa as well as the highest freestanding mountain in the world. At 19,341ft/5,895m above sea level, the group's members, mainly composed of students, were climbing almost six kilometres above their norm of Brighton, often in sub-zero conditions. No mean feat. I should know, I’m one of the students.

It took us four nights to reach the peak and only one night to descend. Of the other groups we met on the mountain, our expedition was by far the most ambitious in size and speed. We comprised 27 climbers plus a team of approximately 75 guides and porters. The other groups we encountered took a much more leisurely trip up the mountain, in say six to ten nights, and often comprising only two or three climbers. Ours, however, was a sponsored climb intended to raise money for charity, so the hardship was certainly worthwhile, albeit challenging.

Our four nights to the top meant that although our intentions were lofty and good, our acclimatization was not, and several of us already began to feel the symptoms of altitude sickness by the third night, myself included. Jessie Griffith, a first year Economics student and generally one of the strongest and most resilient climbers in the team, began to hallucinate on approaching the summit, stroking the rock face whilst wondering aloud, “Why is everything made of diamonds?” She joked later: “It would be worth climbing the mountain again just for the trippiness at the top.”

Matt Hall, Expedition Co-Leader and all-round reliable rock of the team, was also similarly struck by the altitude and became convinced that he saw a washing machine somewhere near the peak. Despite such symptoms, however, Matt led well and was impressed by everyone else in the group too, telling me afterwards: “I’m really proud of the whole group, they all performed so well throughout their fundraising and really showed what they were made of in the climb itself.”

I myself collapsed from exhaustion several times close to the summit and at one point curled up into a foetal position on the scree, hallucinating that I was back in England amid a bright, breezy meadow on a warm summer’s day. One blink of the eyes and I was back in the freezing, barren environment of rock, gravel and dust. I stood up and carried on.

The thinness of the air at such altitude means that less oxygen enters the blood via the lungs, and therefore less oxygen reaches the brain, resulting in symptoms such as hallucination, nausea and vomiting. Thus the necessity to climb gently and acclimatize gradually. Our guides and porters, being born and bred in Tanzania, already had much stronger constitutions than us, with their ultra-fit bodies having acclimatized naturally and produced the necessary extra red blood cells to combat the lack of oxygen. As a result, we were constantly playing catch-up with them and it would be fair to say that our porters put us to shame in the climbing department, despite our carrying much less than them.

Other symptoms of our being unaccustomed to life on the mountain were sporadic and aggressive attacks of the dreaded ‘Kili Belly’. Several students (who shall remain unnamed) reported not having had a solid bowel movement for the entire climb.

Our expedition had two main goals: 1) to reach the summit of Mt. Kilimanjaro; 2) to raise £75,000 for the charity Childreach International. Both goals were achieved.

Before the climb we visited Lotima Primary School in Moshi, Tanzania, where we saw first-hand the good work that Childreach International does. The money we raised will go some way to help the charity fund new building works, including classrooms and toilets, as well as fund staff and teaching at other similar schools and orphanages. As an example, £16 provides the books necessary to sustain a Tanzanian child throughout his entire primary education. £1,800 would pay for 10 new toilet blocks in that same primary school, thereby providing a healthier and more dignified environment in which to learn. We met with the 300 pupils of Lotima Primary School, who welcomed us warmly by singing the Tanzanian national anthem. We joined them in a tour of their school and then in sports such as football and netball. We also gave them tennis racquets and a cricket bat and taught them the rudiments of these new sports to complement their current past-times, plus gave them more academic and useful gifts such as calculators, pens, pencils, writing books, shoes and clothes. I was grateful to see the real difference our efforts were making to the lives of these children. It was a humbling and insightful day and reinvigorated our resolve in time for the sponsored climb.

Ashley Farrell, Student Fundraising Manager at Childreach International, told me at our final meeting before leaving for Africa that ours has been one of the most successful university expeditions, charity-wise. Many of us raised the funds by putting on various entertainment events or selling home-baked cakes and cookies on campus. I myself founded the club night ‘Bada Bing’ at local Brighton nightclub Madame Geisha on East Street, and raised a great deal of my pledged target that way.

Firoz Patel, the founder of Childreach International, came to meet our team in Moshi, Tanzania, and personally thanked us for our efforts, congratulating us on raising such an impressive amount. He explained how the funds we’ve raised could have a great impact in any of Childreach’s various projects throughout the developing world. Childreach works at a grassroots level in many countries including Tanzania, Ghana, Uganda, Nepal and India, providing children with access to education and healthcare by empowering local communities with much-needed infrastructure and resources. The charity was established in 2004 and has already made a name for itself as a positive force in the developing world.

Regarding the climb itself, I’m pleased to report that despite various bouts of altitude sickness, of the 27 original climbers an impressive 26 of us reached the summit of Mt. Kilimanjaro (Stella Point), 25 of whom made the absolute peak (Uhuru Peak). So it was a successful expedition by all accounts. All of us pushed ourselves physically and mentally as individuals, as well as supported each other commendably as a team. I feel very proud to have been a member of such an admirable and successful expedition. Tara Rogers, a particularly sports-loving member of the team and manager of local Brighton business Keman Sports, summed it up succinctly when she told me, “Climbing Kilimanjaro was truly an amazing and rewarding experience!”

Our lead guide, Herman Tesha, told me that ours was an exemplary team and that he had genuinely enjoyed leading us to the peak. It was his 149th summit – a staggering feat. And I can happily report that just this morning Herman has reached the peak again, now for his 150th time, with a separate group. Herman’s relentless trips to the summit have earned him the nickname ‘The Herminator’. His mantra: “It’s not about the destination, it’s about the journey.”

Another local stalwart of the East African mountaineering circle is Henry Lauwo, a fourth-generation Kilimanjaro climber in his own family line. His great grandfather, John Lauwo, a guide from the local Chagga tribe, was officially the first man to reach the summit of Kilimanjaro with the first European missionary to do so, Hans Meyer, in 1887. Henry claims to have summitted 228 times and has many interesting and inspiring philosophies regarding Kilimanjaro. He believes that the best way to approach the mountain is to liken it to an elephant. The only way that lions (i.e. mountaineers) can defeat an elephant (Kilimanjaro) is as a team. He would remind us gently of this any time we were struggling. His support, experience and general good humour were of great help throughout.

Other key phrases that one hears repeatedly on Kilimanjaro are “Pole, pole” meaning “Slowly, slowly” in Swahili; “Hakuna haraka” meaning “No hurry”; and “Nguvu komma simba” meaning “Be strong like a lion”.

As far as wildlife is concerned, however, there are no real lions to be seen on Mt. Kilimanjaro. There were a few blue monkeys living in the trees in the thick rainforest-like bush near the base of the mountain, but once we passed through the cloudbank the only real creatures we saw were the occasional crow and the odd mountain spider or mouse. Even mosquitoes don’t make it up the mountain due to its intimidating altitude, so at least we were spared their bites and the threat of malaria.

Kilimanjaro itself is technically a dormant volcano and isn’t really a prime location for life to thrive. The name Kilimanjaro is said to come from the two Swahili words ‘Kilima’ (meaning ‘hill’, or ‘little mountain’) and ‘Njaro’ (meaning ‘white’ or ‘shining’). This was probably a local joke, referring to such a massive mountain as merely a hill. It also used to be a lot more snow-capped, even as recently as the 1970s, although thanks to global warming its white cap has visibly diminished somewhat. The view from the peak is still immense though. Tanzania is truly a beautiful and peaceful land and we were all lucky to see and experience her the way that we did.

Katie Makinson, Expedition Co-Leader and a second year Economics and German student who lives in Kemp Town, said: “I was very impressed with our entire team. I’m just so proud of everyone. It’s a massive achievement. This climb was much tougher than last year due to the route, the weather and the timing. I was particularly impressed with the determination of everyone who was sick, especially on the tougher parts of the climb like the Barranco Wall.” The Great Barranco Wall is an 800ft vertical section of jagged cliff face that most climbers reach on their fifth day. We, however, were tackling it on our fourth – and later that night we were attacking the summit, something most climbers don’t do until their sixth day. Katie, a particularly sporty student who is also university Dance Captain as well as President of Tennis, has now climbed Mt. Kilimanjaro twice, over two consecutive years, and believes that the impressive endeavours of the students on this year’s expedition will help to boost Sussex’s reputation as a sporting university.

Sarah Hall, Sports Administrator at the University of Sussex Students’ Union, was also one of the 27 members of the expedition and told me about her current feelings of pride as well as her original feelings of trepidation before joining the expedition: “Juggling fundraising, a fitness program along side work and meeting 26 strangers with whom I was going to be climbing the world’s highest freestanding mountain scared me quite a bit. But after conquering such a huge challenge, and seeing some of the most beautiful sites, I wouldn’t switch one of those 26 other people for anyone. You truly do make great friends in the strangest of places and for me that happened on the roof top of Africa.”

After reaching the summit, despite having taken four nights on the way up, we only camped for one night on the way down. So our descent was much faster than our ascent. This resulted in at least four girls in the team suffering from painfully swollen lips, due to water retention brought on by the sudden change in altitude. Some grumbled at the discomfort while others seemed more bemused by the free collagen-like cosmetic effect.

After descending and returning to Nairobi, Kenya, I happened to meet a newly-wed American couple who had spent their honeymoon climbing Kilimanjaro, and who claimed to have observed our expedition’s gradual decline into illness, to comic effect. Eric and Louise Cooperman, who had climbed the mountain at a much slower and safer pace than us, described to me how they had observed us “falling apart” as the expedition progressed. Louise recalled seeing us turn “from a chipper group on Day Two to a crying group on probably Day Four”. They also described seeing several of us later staggering around the peak, dazed, groggy and “looking wrecked”.

Despite the hardships, however, climbing Mount Kilimanjaro is an epic experience and a wonderful test of one’s personal strength, stamina and compatibility within a team. It certainly wouldn’t be an achievement if it were easy. I shall take away with me many fond memories of trekking through the scree, climbing the rocks, laughing with friends, and playing cards in the mess tent. I will happily recollect the general camaraderie and good humour of the group as well as learning the Swahili language, customs and traditions from our generous porters and guides. The porters are truly the unsung heroes of Kilimanjaro. At the end of the climb we rewarded our faithful helpers by divesting ourselves of much of our climbing equipment, giving it to them in thanks for their support. I also shot a great deal of video footage during the climb which I will be editing into a full-length documentary in the coming months. In the mean time, I look forward to reuniting with the many new friends I made during this exciting and life-changing expedition.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here