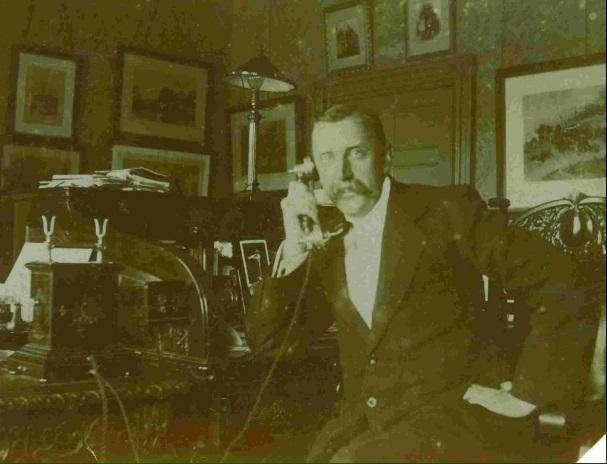

ALDERMAN Sir Herbert Carden was often referred to in his lifetime as the maker of modern Brighton.

Born in 1867 to a longstanding local family, he became a wealthy lawyer who also served on Brighton Council for 41 years.

Although he was a socialist in a Tory town, Carden was listened to with great respect by the ruling Conservatives. He was behind the council’s plans to run tramways, which it did with great success from 1901 to 1939. When municipal control was welcomed by Tories as well as socialists, he put forward plans to run electricity locally and for managing a water supply.

The clear, clean water under the Downs which was pumped into people’s homes was among the best and cheapest in Britain. It was partly because of this underground water that Carden and the council became interested in protecting the Downs.

But councillors also acted to preserve the hills to the north of Brighton from becoming like another Peacehaven. Because sellers of land would have increased the price had they known the council was a buyer, Carden bought land himself and sold it to the council at cost price.

In the 40 years after 1895, he reckoned the council bought 12,000 acres of land for about £800,000. Carden also bought sites outside the borough’s borders such as the Devil’s Dyke. Carden said he once went to London to buy a few acres of downland at Hollingbury and added: “When I got there I bought the lot.”

He alas campaigned for Greater Brighton to be created by moving the boundary northwards beyond the built-up area. Carden gave £1,000 for one of the two concrete pylons on the A23 which now mark the line. Most Brighton people approved of Carden’s downland safeguards and he was duly honoured. He was wartime mayor for three years and was made a freeman before being knighted in 1930.

But there was much more controversy over his plans for the town itself. In the 1930s, Carden was an enthusiastic supporter of the newly-built Embassy Court on the seafront close to Hove.

Many other people thought the 13-storey tower an affront to the seafront and a bad neighbour for the historic buildings next door.

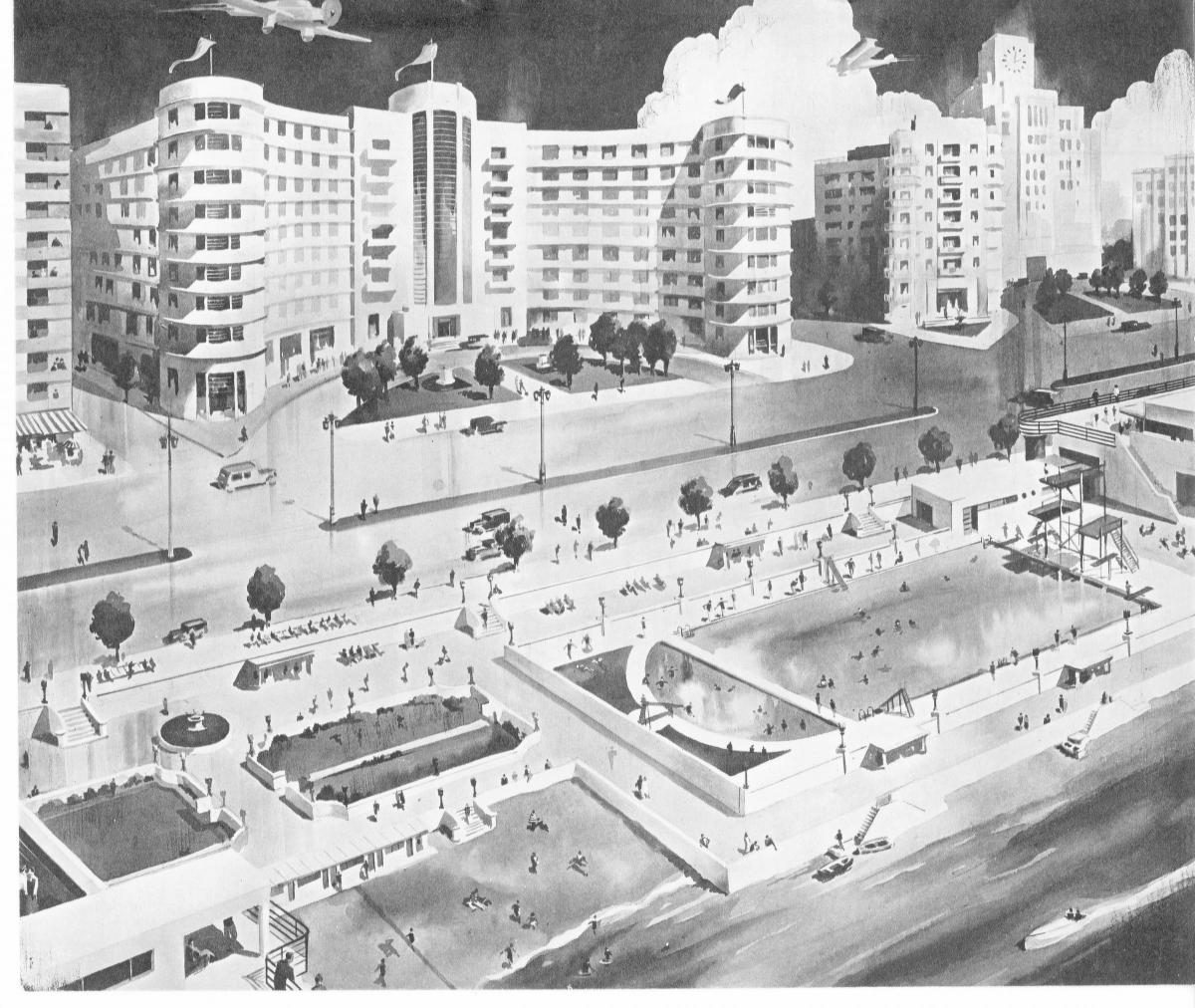

Carden’s vision was to demolish all the seafront homes from Hove to Kemp Town. He produced a drawing and envisaged a mile or more of modernist buildings strangely similar to Embassy Court – handsome but in the wrong place. “Even Sussex Square will have to go,” said Carden as he faced his critics.

Carden was greatly assisted by the eminent town planner Sir Charles Reilly who lived in Brighton and who had modernised Preston Manor.

He also still had backing from some Tory councillors who forsook party loyalties to back a man who was doing his best for Brighton. In his defence, Carden lived in an age when Regency masterpieces were expected to crumble and be replaced. There were no listed buildings or conservation areas.

Even the Royal Pavilion was regarded by some as a dreary fantasy but there were still many who sprang to the palace’s defence when Carden proposed that it should be demolished.

He wanted it replaced by a modernist pavilion like the De la Warr Pavilion at Bexhill – Carden greatly admired its architect, Erich Mendelsohn.

Of the Royal Pavilion, he simply said: “It is a complete anachronism in this modern age.”

Historian Clifford Musgrave, who also happened to become director of the Royal Pavilion a few years later, naturally did not agree.

He said: “It was the one blind spot in his otherwise remarkable vision of Brighton’s future.

“He did not live to see the Prince Regent’s Pavilion become the envy of every resort, not only in Britain but throughout the world.”

Carden without doubt would have been intrigued by the protection given to the seafront today and the fact that most of the buildings he advocated pulling down are still standing. Both the Regency and Brighton Societies have been formed to save Brighton from more monstrosities such as Sussex Heights and King’s West.

When Carden died in 1941, he knew the war had effectively prevented any move to redevelop the seafront but the Pavilion plan had been rejected long before that. But Carden’s downland remains as a memorial to him 75 years following his death and Carden Avenue in Hollingbury was named after him.

There are many Cardens still in Brighton and Hove and one of them is Bob Carden, who became mayor of the city. Bob Carden is a doughty defender of the Downs and campaigned hard to stop the Brighton bypass from being built. There is little doubt Sir Herbert would have opposed the current plans to sell off public downland even though the money would be used to improve Stanmer Park.

Stand on the Downs on a quiet, windless night and the faint groaning noise you hear will be that of Alderman Sir Herbert Carden turning in his grave.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here