"I saw Robin Williams on stage doing that non-stop rabbiting away before he turned into a film actor. I thought, ‘I’m watching myself here!’, flashing from one thing to another. Proactive is what I am!”

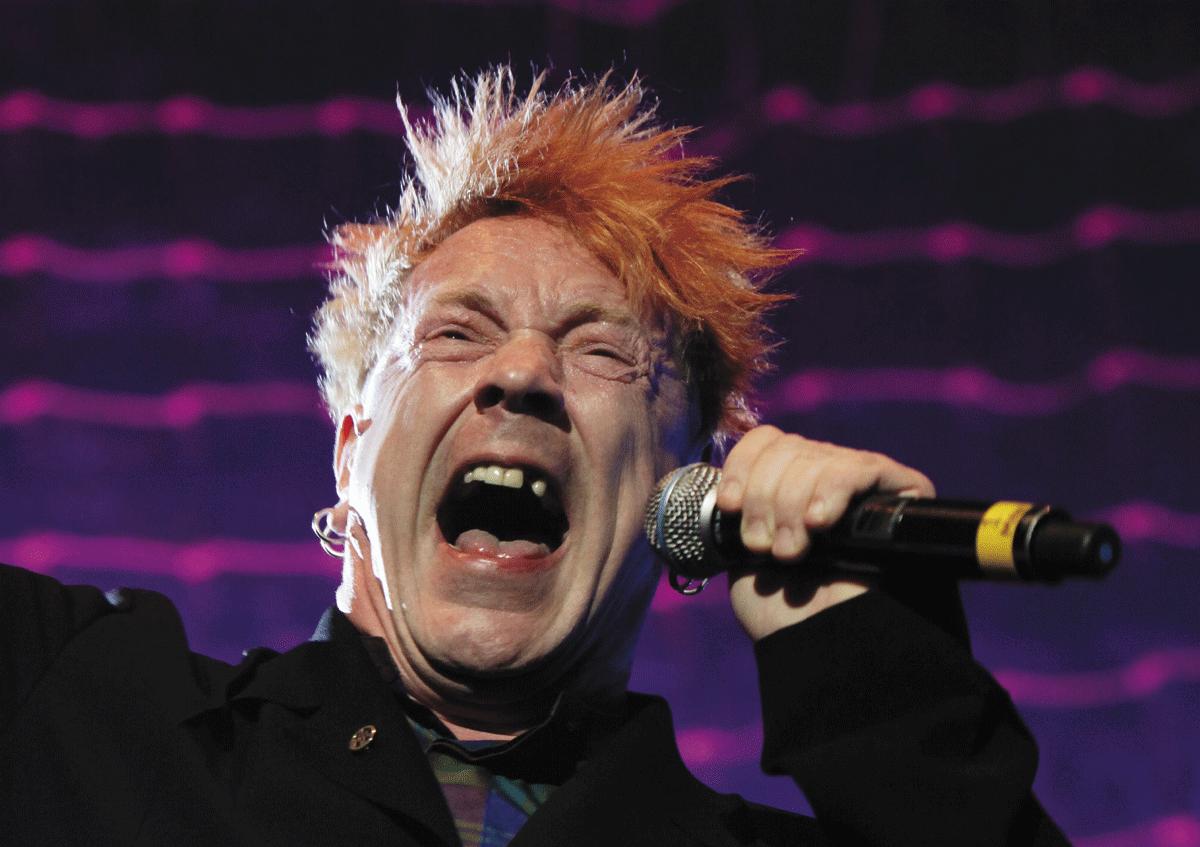

Talking to John Lydon on the phone from his Los Angeles home is exhausting. In our 45-minute conversation, he jumps from topic to topic – from the global financial crisis to his role in punk, to revealing he has learnt how to control his dreams to work through any problems he has.

It is unsurprising that he became the mouth-piece of the punk movement when it exploded on to the national consciousness after his band the Sex Pistols’ four-letter-word-strewn contretemps with the late Bill Grundy on prime-time television in December 1976.

“He was a dirty old man,” remembers Lydon. “We were just kids. In many respects I never had a childhood – it was people like him who stole it off me.

“It was an interview none of us wanted to do. Queen cancelled and they asked us, ‘Quick, can you fill in?’ Would he have been nice to Freddie Mercury?”

It's all about PiL

Although Lydon is happy to talk about his past, it is the present he is most interested in – especially now his band PiL have finally gained control over their destiny.

He reunited with former bandmates Bruce Smith and Lu Edwards – along with multi-instrumentalist Scott Firth – in 2009 for a series of shows, out of which came the band’s first album in 20 years: This Is PiL.

“I’m working with people I really trust and totally respect,” he says. “It’s a great scenario. The hard work is beginning to become overwhelming – we’re trying to run a record label, manufacture records, run a website, book and play gigs, and keep it honest. It’s a lot of work but when you fight for your independence, you get it! It sounds like I’m moaning but a bit of hard work never hurt anybody.”

That desire for independence came from bad experiences with major record labels, which eventually led to his band’s 17-year hiatus following the release of the last PiL album, That What Is Not, in 1992.

“I had to find a way out of the crushing debt that the labels had put me under,” he says.

“The financial support was cut off and I had nowhere to go until I raised money to pay what they cleverly called recoupment.

“A few bands have gone down that way – it has driven many people to drug addiction and alcoholism. You can get wrapped up in self-pity, but I had a long time to get over that and get over trying to get even.

“The record labels tried to murder me for years, but if anything they have made me fine tune what I’m doing here. I’ve got back into making music and writing songs.”

Celebrity profile

Following the writing of his autobiography Rotten: No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs in 1993, a reunion with his original band the Sex Pistols in 1996 and his first solo album Psycho’s Path, he eventually built a more public profile through his appearance on I’m A Celebrity... Get Me Out Of Here! in 2004.

“I’m A Celebrity raised £250,000 for charity,” he says. “I could have done with that money at the time, believe me!

“To me, I’m A Celebrity was about how long I could endure whining, moaning, silly-minded people. If you keep your heart-rate down and go with the flow, you fit into everything. If you go around complaining about how uncomfortable you are, you’re going to go through hell. It’s self-inflicted.

“For the first time ever, people had the opportunity to see what I’m really like.

“I love life, I love anything with a spark in it. I could sit and watch ants all day. I found this enormous 3ft-long iguana with huge claws on top of a log one day. He had no problems with me – he just carried on enjoying the sun, which is what I did too.”

After the show, Lydon was approached to front other nature programmes – John Lydon’s Megabugs, Goes Ape and Shark Attack, which saw him share the ocean with great white sharks in South Africa.

Then came the controversial adverts for Country Life butter, which led to sales of the food stuff soaring and provided the money for the PiL reunion.

“I couldn’t ask people to hang around for ever when there was no money,” says Lydon of keeping his band PiL together. “Money problems directed the pace and affected the membership – all 49 of them!

“God bless them – I love every one of them. Every member offered a different angle.”

Indeed, PiL is a band which has morphed rapidly from album to album – and even within records. The band’s second album, Metal Box, still sounds like it comes from another planet, despite only being made two years after the Sex Pistols’ Never Mind The B******s.

Accompanying single Death Disco’s combination of Lydon’s heartfelt lyrics inspired by the death of his mother, Jah Wobble’s dub basslines and Keith Levine’s Swan Lake-inspired guitarline is still a stunning and unforgettable listen almost 35 years on.

“What I found from the Sex Pistols onwards was that I wanted to be free from restraints and restrictions,” he says. “I wanted to explore any territory my brain fits me into. PiL created an entirely new musical landscape.”

Back to Brighton

He admits he sees albums simply as a way of creating more material so the band can continue to perform live.

The band were last in Brighton in 2012, playing Concorde 2 in Madeira Drive.

“Brighton gave us an amazing response – it was the best seaside holiday ever!” he says.

“After all these years I’m still nervous about going on stage. It’s an amazing thing when you’re communicating that closely with an audience.

“That intimacy between us and the audience has been missing for these 20 years – I think that’s what people came back for. “The audience are the driving force, they pick up on what I do and feed me with ideas. It becomes a perfect balance.

“It’s like a communion without the idolatry. It’s how popular music should be.”

Much of the album itself was improvised in the studio, with Lydon and guitarist Edmonds fitting together well.

“We can trust each other in a musical way to push it that extra bit, to reach higher or lower, calmer or more insane,” says Lydon. “It creates such a lively spontaneity twisted inside the songs – they become deeply emotional.

“Many people think music is mechanical, but it’s not at all.

“I have no mechanical brain whatsoever – I’m like the random key to the universe! Lu counts his beats and structures in mathematical ways, so we complement each other.

“We hit the right moments together. With our live performances, it’s like a knife edge – in a heartbeat it could go enormously wrong. It’s been a very difficult, long road to get to this point but it’s been worth it.”

Banding together

He describes This Is PiL as not just his own experiences but also that of the band.

“We didn’t have any rehearsals,” he says. “The songs were improvised from conversations we had and the way we know each other.

“All of us have suffered, all have come from different backgrounds. When you sit down and talk honestly to people it is amazing what you can achieve. The songs don’t become an agenda you have to overcome – they become a vitality.”

The making of the album came at a particularly difficult time for Lydon, who lost his father and his step-daughter, Ari Up of The Slits, just before the band went into the studio, and believed his brother was also facing terminal cancer.

“I could have wrapped the album in death, misery and self-pity but I didn’t,” he says. “I put those things on the back burner to deal with later. I wanted the album to be happy. The content of the album is serious but I wanted it to be something my father would be proud of rather than sticking it to everyone again.”

He denies any suggestion that he might have mellowed, though – attacking it as a journalistic cliche.

“I’m a long way off mellow, me!” he laughs. “I’m trying to spark thoughts. If some people take issue with it, then at least they are thinking and either way we get results.

“All my life I thought my father was making my life a misery when I was young. He was educating me not to take things seriously – to have that sense of fun. It’s the Irish side of me.”

Indeed, the album is sprinkled full of jokes and puns from the man who once memorably rhymed antichrist and anarchist – including the title track’s announcement that “This is quite a-pil-ing” to Lydon’s opening statement on One Drop, “I am John and I was born in London. I am no vulture, this is my culture. We come from chaos, you cannot change us.”

Abundant energy

Lydon attributes his “high energy and restless brain” to his father.

“Once I’ve sussed out the plot of a book, what’s the point?” he says. “I like things to be random and unanswered. The thing I love about music is that it is unanswerable – you will never reach the final conclusion, there is always another possibility.

“I don’t do anything in life to remain in stasis. I view my life as a journey of exploration.”

He has always been energetic and restless, which led to his first battles at school.

“I was at school before ADHD and all those excuses,” he says. “I was bored of the subjects – our brains are capable of absorbing much more serious information but don’t get that outlet.

“My mother taught me how to read and write at the age of four. At school I was frustrated, watching kids take two years to do what I already knew. I was left-handed, which was a sign of the devil. They made me write with my right hand, but I got through it.

“My constant message to everyone in the world is to educate yourself – institutionalism is not the same as education. You have to learn to read between the lines when you’re being fed information.”

In recent years, he has seen the gradual veneration of punk from its anti-establishment roots to something which is celebrated, with whole evenings devoted to it on BBC Four.

“It’s creepy,” he says. “It’s not pleasant to see people waltzing through my past in that way. They are taking the life right out of it and turning it into a museum piece. I find it deplorable and degrading.

“I’m taking punk into the 21st century but meeting resistance from this little cottage industry which has been living off punk bands and not showing any gratitude about it.

“They keep coming up to me with fresh rules. When PiL started, people were coming out with punk rule books and expecting me to adhere to variations of what I started.

“As long as you don’t hurt anybody else, there are no rules in punk – that’s the point.”

As for the future, who knows?

“Somehow or other people have come to the conclusion that what I’m doing is worthy,” he says. “It’s certainly original and creative.

“I haven’t allowed myself to become a cliche. I’ve given myself a future.

“We will find a way of f***ing it up – we’re not the lads to sit around and get too comfortable! The challenge is to curtail our wilder excesses. I have all the time in the world.”

See the related event for details on PiL's show on June 27, 2013

There's a timeline of John Lydon's career alongside this feature, and more besides, in The Guide (June 21). Pick up The Argus every Friday for more great features and previews inside The Guide

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel