FIRST LIGHT: STILL – A 30 YEAR RETROSPECTIVE University Of Brighton Gallery, University Of Brighton, Grand Parade, until August 20

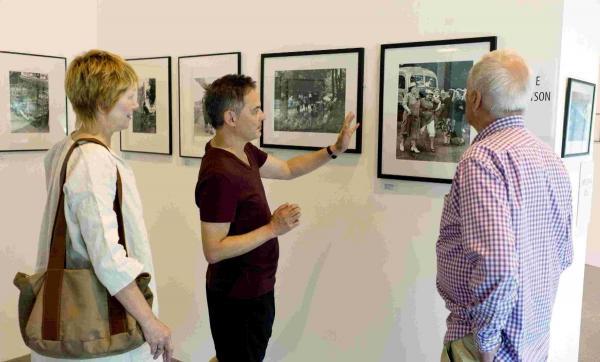

THE comments book at First Light: Still says it all. Packed with superlatives – from “wonderful, wonderful” to “extraordinary, rich and varied” – curator Mark Nelson is clearly pleased with the response the exhibition has had from the 1,000 visitors it has welcomed so far.

“It’s full of supportive comments,” says Mark Nelson. “It shows the enthusiasm for an exhibition like this. Brighton needs this sort of space – hopefully it will inspire the Faculty Of Arts to offer it up to more independent curators.”

This is the first exhibition Nelson has curated himself since closing his Nile Street gallery last year after more than 30 years in Brighton.

First Light, which opened in 1981, had begun as a fine art printing lab run by Nelson and his wife Anna, who had moved down from London to enjoy the pace of life in Brighton. The studio gallery featured works printed at the lab destined to go to exhibitions across the world.

He admits the larger size of the space in the University Of Brighton was slightly daunting.

“It’s probably about four times the size of First Light,” he says. “That gallery was a great space but it was so constricting. When you’re a photographer working with other photographers there is a phenomenal amount of work from their portfolio you aren’t able to show.”

He sees First Light: Still as a new phase in his career, following an invitation to display his own exhibition This Being: That Becomes at Berlin’s White Concept Gallery in May.

“I was keen to show part of my show in Brighton, but I also wanted to show the work of other photographers who I had exhibited at the First Light gallery,” he says, adding he now splits his time between Berlin and Brighton.

The plan was to focus on First Light exhibitors who were either well-known or had become well-known after displaying their works at First Light.

He narrowed the list down to 11 photographers, including many with strong links to the university, such as Grace Robertson and Roger Bamber who have both had honorary degrees conferred onto them. He also found room for a personal inspiration, Americana pioneer Walker Evans.

“I approached each photographer and asked them to give me eight images of their choice,” says Nelson, admitting once he had the images the exhibition came together quite quickly.

“It’s like writing – some days you get really stuck, some days it just flows. This exhibition just seemed to curate itself.”

It’s surprising with the variety of work on offer.

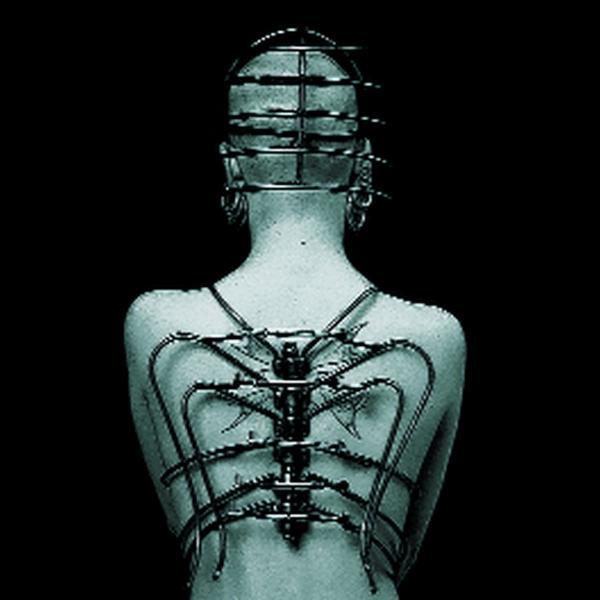

The photographers Nelson approached ranged from photojournalist couple Thurston Hopkins and Robertson, who both worked for Picture Post magazine, to fine artist Axel Hesslenberg, whose four pictures of peonies suspended in space still puzzle Nelson as to how he did it, to Nicholas Sinclair who has provided a series of images documenting the UK’s fetish community.

As Nelson introduces the exhibition certain themes make themselves apparent.

Brighton features heavily, not least in the work of Bamber whose beautiful image of the wrecked West Pier surrounded by starlings holds pride of place in the second room, and Steve Parry's timeless images of life around the seafront, which could come from any period in time.

And there is particularly starry selection of images – all with a story to tell.

In the entrance to the exhibition is a rare shot of UK playwright Samuel Becket outside the Royal Court in 1979 by Paul Joyce.

“Joyce sort of knew Beckett but was told he didn't want his portrait taken,” says Nelson. “Joyce had piled up a load of rubbish and set up a camera on a tripod. He encouraged Beckett to have a quick look and he eventually agreed to do the shot. It's one of the few of Beckett where he's almost smiling!”

Similarly Robert Redford wasn't keen on Joyce getting so close with his camera in 1993 when the portrait photographer came up to him with a wide-angled lens, capturing every line in the screen idol's face.

And part of the reason Bamber managed to capture such a natural laugh on Mick Jagger’s face following his wedding in Barbados to Jerry Hall in 1983 was because the photographer had just been soaked by a huge wave while trying to get a beach shot.

Other icons scattered through the exhibition include George Best, Francis Ford Coppola, Dirk Bogarde and a platinum print of Paul Scofield in 1990 by Nicholas Sinclair reputed to be one of the Balcombe-based actor's favourite shots.

The portrait which has been drawing most interest from visiting photographers is another Paul Joyce shot from 1976. It captures a trio of legendary photographers, Bill Bradt, Brassai and Ansel Adams, talking together on the other side of the camera.

“When Grace Robertson saw it on the opening private view she said it was three of her all-time favourites," says Nelson.

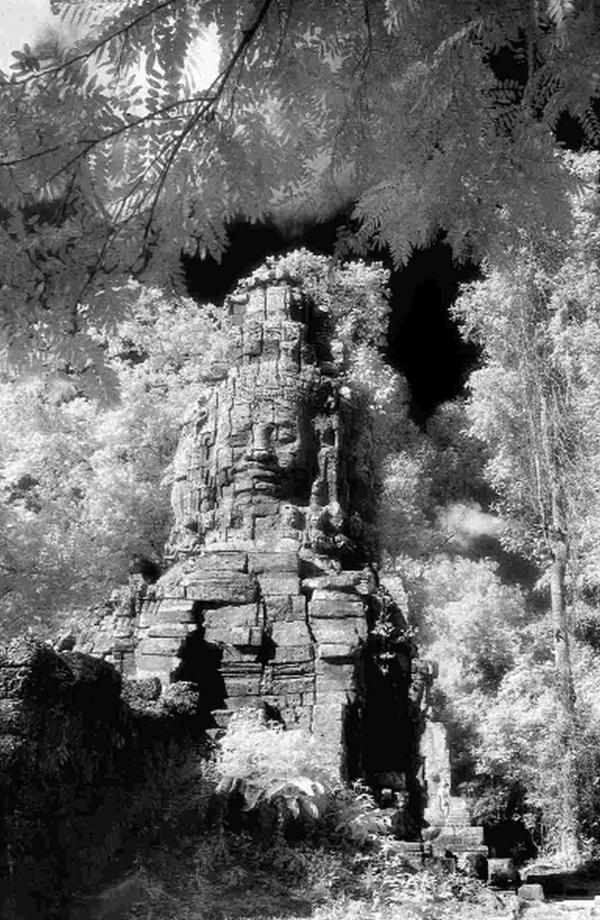

The pull of America is also a major theme - most obviously in the shots from Evans, taken for the Farm Securities Administration in the 1930s to document the poverty in the Deep South of the US.

“When Evans presented these pictures to the administration he was told they were not only wonderful photographs but great works of art,” says Nelson who bought the displayed images taken from the original glass plates in 1990. “He captured people who were still well turned out despite their poverty, but also some of the buildings and the advertising artwork which would inspire pop art.

“It became the genre called Americana.”

There are plenty more examples of Americana running throughout the exhibition - not least in Nelson's own work.

“I love the idea of a film set,” he says. “Some of my own personal work has that quality.”

His section of the exhibition features images of Central Park's Woolman Rink resembling a modern day L S Lowry image, an Edward Hopper-influenced shot of Greenwich Village in 1991 which could have come straight from 1945, and a particularly ominous shot of the Brooklyn Bridge from 1987 with the World Trade Centre shrouded in mist.

Elsewhere there are Bamber’s documentary images of the US Amish community, Perry's take on the iconic Chrysler Building, and a selection of American images from Christopher Joyce, a photographer best known for his work in advertising.

The display case at the front of the exhibition contains the Clifton Road photographer's hat which he used to wear on photojobs.

“Joyce died about 20 years ago,” says Nelson. "I went to see his wife and children when I was putting this together to see if they had any work of his they could give me.

“There was a whole exhibition he had prepared 20 years ago which they lent me alongside his hat. It was great to have these images he wanted to show himself.”

The selection of shots from between 1989 and 1992 range from images of a Pride parade in New Orleans to a “face” captured in a viewing telescope at the top of the Empire State Building.

There’s also plenty of advertising signage, in a nod to Evans's original imagery.

First Light: Still has plenty of imagery from an England long gone too – largely courtesy of Seaford-based photojournalists Hopkins and Robertson, who was the first female photographer to work on Picture Post.

As with much of the imagery on display the shots are black and white, flickering backwards and forwards in time.

A Bermondsey hen night from 1954 has a strange resonance with the revellers found in Brighton’s West Street most weekends. But an image of bird sellers of Petticoat Lane in 1948 clearly comes from another era, albeit still within living memory.

With so much on show it is not surprising that one of the most popular spaces in the exhibition has been Nelson’s Quiet Seat – allowing visitors to look at both his images and his catalogue, while listening to the subtle musical textures he has composed to go alongside his own work.

“I was a musician before I was a photographer,” says Nelson. “I was influenced by Brian Eno's sound installations – using computer programmes to develop a sound texture which gives a sense of resonance to the pictures.

“It’s almost a cinematic quality. We go to the cinema to see images and hear soundtracks, but you don't get it at exhibitions - partly because it has to be incredibly subtle and appropriate for the images.

“You couldn't have something like The Rolling Stones's Tumbling Dice playing!

“I would go as far as saying this isn't music, but sound texture.”

And so, as he looks back at 30 years of photography, Nelson is also giving an indication of what could be a staple of the exhibitions of the future.

Open Mon to Fri (no weekend opening) 10am to 5pm, free. Call 01273 643010.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here