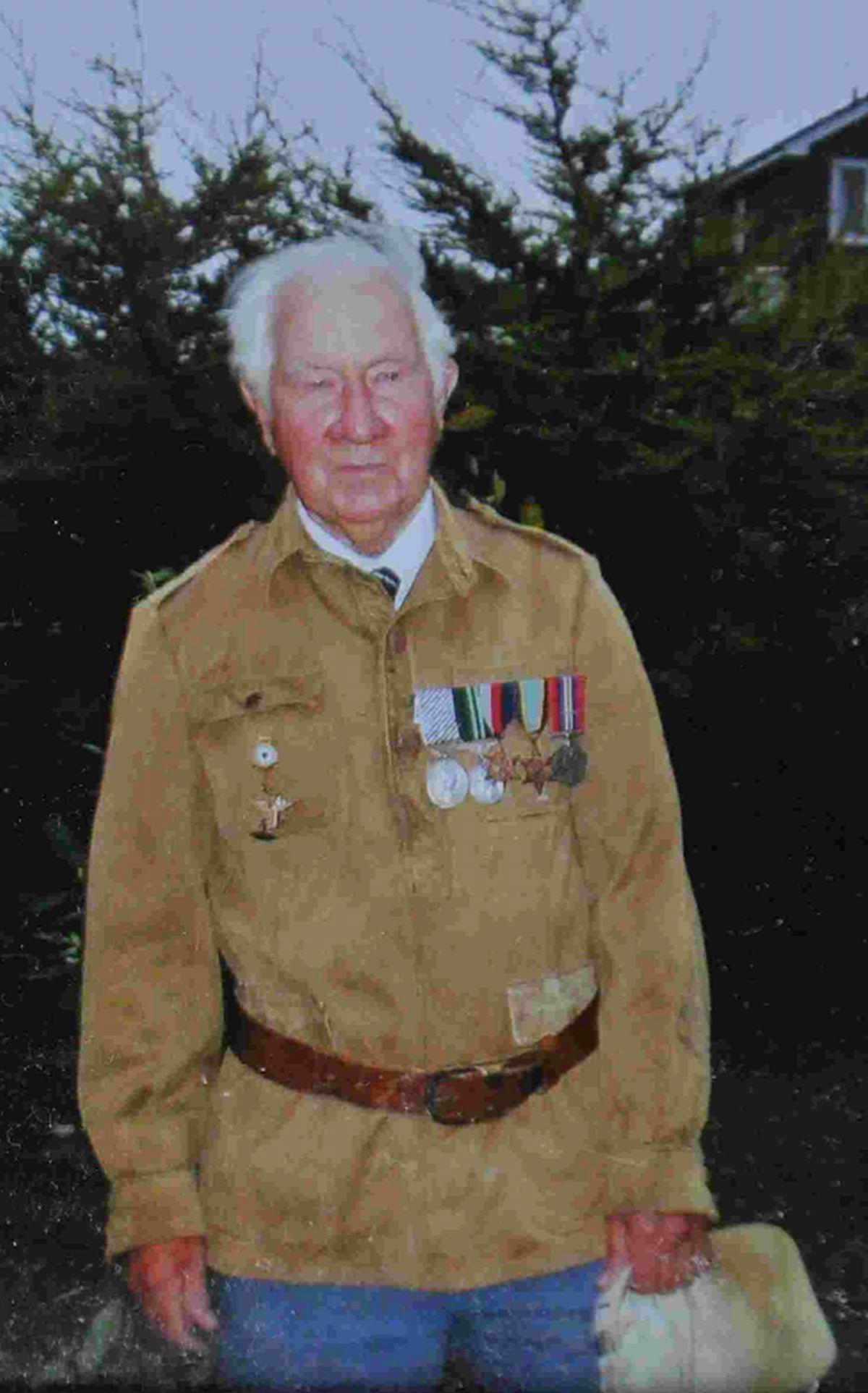

John Akehurst was a loving father, husband and popular landlord.

Many will remember Mr Akehurst from his time running the Hampton pub in Upper North Street, Brighton, in the mid 1950s before moving to Ye Olde Smugglers Inne in Alfriston a decade later.

He died in hospital in November aged 96 having spent his final years in a modest house in Peacehaven.

But unbeknown to those around him, he had another incredible life during the Second World War.

After joining the Royal Air Force (RAF) in 1938, he went on to be one of the most experienced members of Bomber Command, clocking up more than 750 flying hours over enemy territory.

As a result he was signed up to Winston Churchill’s top secret Special Operations Executive (SOE) and carried out covert missions, including the assassination of Hitler’s right-hand man Reinhard Heydrich.

After crashing in Germany he was taken prisoner before embarking on a number of daring escapes.

He endured brutal interrogation, beatings and starvation and a Nazi court martial before being taken to the high security Stalag Luft III prisoner of war (POW) camp – best known for being the scene of The Great Escape film starring Steve McQueen, Richard Attenborough, Charles Bronson and many others.

Mr Akehurst was locked in solitary confinement, preventing him from getting out through the three hand-dug tunnels codenamed Tom, Dick and Harry.

After being transferred to various camps as a high security prisoner, he was made to go on what was dubbed The Death March.

With the Germans facing defeat, thousands of POWs were forced to trek across northern Europe with little food or provisions in the most appalling blizzards.

Mr Akehurst again attempted escape and hid in woods before being recaptured.

He returned to his home in Eastbourne in 1945 and went back to his desk job at a brewery in Terminus Street.

He kept much of his incredible story to himself – until now.

His son Roger pleaded with him to write it all down. He feared his request had fallen on deaf ears but following Mr Akehurst’s death, he found a small notepad titled Last Freight Jake’s War – Last Freight Jake being his nickname in the POW camps.

The family also found his POW logbook. The small booklets were intended to keep prisoners’ minds busy by providing space to write letters and draw. Mr Akehurst’s is full of sketches of camp life, cartoons, aircraft, poems, collections of cigarette packets and the names and addresses of some of the people he met along the way.

Now, for the first time, we can tell his incredible story – in his own words.

Born in Guilford in 1918, the year the First World War ended, his family moved to Hellingly, near Eastbourne, where he was a choirboy and worked as a runner on the local paper. As a teenager, Mr Akehurst was a promising cyclist and broke club records as a member of Eastbourne Rovers.

He worked in accounts at a brewery in Eastbourne but with war approaching in 1938, he answered his country’s call and joined the RAF at a recruitment office in Hove.

He trained as a wireless operator and air gunner and was drafted into Bomber Command, the RAF’s ground attack unit.

After being moved from squadron to squadron, base to base, he began bombing raids in 1940, many of which were attacking military targets and later German cities at night.

Bomber Command had among the lowest survival rates of any unit in the war, with 55 out of every 100 men killed in operations or dying as a result of their wounds. Only 27 in every 100 survived the war unscathed.

However, despite the danger there is no hint of fear in his dairy. Quite the opposite, he almost appeared to enjoy it.

In early 1941, Mr Akehurst was involved in a number of high-profile missions, one of which was to sink the great German battleship Bismarck.

Having gained a reputation for his skill in the air, he was recruited by SOE in July, 1941. Known as Churchill’s Secret Army, given the wartime leader’s role in its formation, SOE was a top secret unit comprised of the best men from all Allied forces. They carried out espionage, sabotage and reconnaissance in occupied Europe and, if caught, were likely to be killed.

One of the missions Mr Akehurst was involved in, described in his diary, was the assassination of one of the architects of the Holocaust, Reinhard Heydrich.

Otherwise known as the Butcher of Czechoslovakia, Heydrich was one of Hitler’s right-hand men.

He personally helped organise the mass deportation and killing of millions of Jews from German-occupied territory before being appointed the acting Reich-Protector of what is now the Czech Republic.

Described by Hitler as the “man with the iron heart”, he was ruthless and brutal in his ways. He sought to eliminate opposition to Nazi occupation in the country by suppressing Czech culture and deporting and executing anyone who resisted.

He was also responsible for the Einsatzgruppen, a special task force that followed in the wake of the German army and killed more than one million, including many Jews.

The Allies hatched a daring plan to fly two specially trained agents, Jozef Gabcik and Jan Kubis, into Prague to carry out the attack.

The Czech assassins, as they were known, were flown over in a Halifax bomber manned by Mr Akehurst and his crew before touching down close to Prague on December 21, 1941.

It was another five months before they picked their moment, as Heydrich made his daily commute through the capital.

As his convertible Mercedes 320 slowed for a corner, Gabcik stepped in front of the vehicle and opened fire. Kubis threw a hand grenade at the car, with shrapnel fatally wounding the high ranking Nazi officer.

By this time, Mr Akehurst had flown countless more secret missions, many involving ferrying spies over to occupied France.

Given the grim prognosis for members of Bomber Command, recruits were told they had to complete a certain number of flying hours before they were discharged.

Given the frequency of Mr Akehurst’s missions, he was approaching his limit in late 1941 and so proposed to his sweetheart, Joyce. They married in September but Bomber Command chief Sir Arthur Harris could not let one of his best men go and called him back up.

Around the same time, he was told he would be awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his bravery and courage.

In mid-1942, he helped spearhead some the first major bombing raids on German cities, including Cologne and Essen.

Even with the war only three years in, he had clocked more flying hours than most.

His logbook shows more than 750 hours of wartime sorties.

His only son, Roger, said: “Given the life expectancy of Bomber Command, he was very lucky. He was obviously very good as he got called up to the SOE but there would have been a lot of luck.

“There can’t be many others with that amount of flying time during the war.”

However, his luck ran out on a bombing raid over Bremen in northwest Germany in 1942.

His Wellington bomber came down and he was knocked out on impact.

Writing in his diary, he speaks of throwing everything he could out of the bomber in an attempt to make it lighter and keep it in the air.

He wrote: “The next thing I remember was an almighty bang and where I was standing seemed to have exploded. I went head over heels up the aircraft.”

They had crashed deep into enemy territory in a bog.

He continued: “I was trapped in the fuselage, there was a fire in the front and no way out of the back. I knew there was a small escape hatch on the side of the aircraft but was buried in earth.”

He recalled sticking his hand out and feeling the “cool air” before shouting for help.

Next thing he knew he was standing by the side of the burning wreckage. Remarkably, all the crew had made it out and they walked off into the distance before the aircraft exploded.

His flight logbook from the war simply read: “Operations Bremen: Failed to Return.”

The group decided to make a move and the five split into groups and headed for shelter as German aircraft circled above looking for survivors.

Mr Akehurst went off with the navigator, Mike, while the other group was quickly caught.

With only four squares of chocolate and one water pack between them, they made for the border – and safety.

They travelled by night, attempting to navigate the German countryside – which was easier said than done.

“Have you ever tried to walk across country in the dark in a straight line?” he asks in his diary. “Well I can assure you, it consists of walking a few hundred yards then coming across a hedge, barbed wire, water or trees.”

They continued like this for two nights, during which the weather turned. They tried to shelter from a storm in a small village but local children discovered them, forcing them to make a run for it across fields.

The local home guard, as he described them in his diary, and their dogs were sent in pursuit. With the search party getting closer, they jumped into a ditch and hid behind a bush. One of the guard’s dogs noticed them but they managed to escape before the owner could arrive.

They continued on the run for two more nights, exhausted by the lack of food and water. They tried and failed to jump on a passing train, but instead headed for a nearby wood.

It seemed like the perfect hiding place, until they noticed the ground moving.

“We had these giant ants crawling on us all day,” he wrote, “still had not eaten since last in England, getting a bit weak owing to shortage of food.”

However, to survive they knew they had to keep moving and after coming across a promising road sign, they made a dash for the Dutch border.

Setting off that night, they came across a cottage but pressed on, thinking they were within touching distance of safety. It was then a figure appeared at the gateway.

“We could not do anything but walk on. Mike called out ‘guten nacht’ [good night in German] and got some reply.”

They hid in a garden thinking they had got away with it but soon noticed they were being followed.

“What we did not realise was that waiting for us a little further was a police car.

“Much shouting of ‘hands hock’ and other words. We were placed in the VW Beetle and on our way to the jail. I had pockets emptied and our boots taken and put in a cell.

“The next morning the policeman was very pleasant, he said he had a son in the Luftwaffe. He gave us our first meal for ten days, which we found difficult to eat.”

Later the same day, two guards turned up at the jail to take the pair to a POW camp.

However, as Mr Akehurst recalled in his diary, he had different ideas.

With both under heavy guard on the public train service, they hatched a plan. When it next approached a station, they were to spring up and run to the door before leaping from the moving train. Mr Akehurst made a dash for it but Mike was obstructed by the guard and a fight broke out.

He recalled: “He whispered to me to stand up and make for the door and jump up. Sooner said than done. Mike got engaged with his guard. I could not jump without Mike.”

The plan had failed and the pair were forced to spend the remainder of the journey with their hands on their heads. “It became tense,” as Mr Akehurst coolly put it.

His daring in trying to escape would not be forgotten by his Nazi captors.

Do not miss tomorrow’s Argus for the conclusion of Mr Akehurst’s story as he is interrogated for weeks, sent to Stalag Luft III (scene of the Great Escape), court martialled by Nazi High Command and sent on Hitler’s Death March

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here