Women have been working in the police since the early 20th century, though they were paid less and were not allowed to do as much as their male colleagues for decades.

Sussex Police are now joining forces around the country in celebrating 100 years of women in policing – but police chiefs say there is still work to be done.

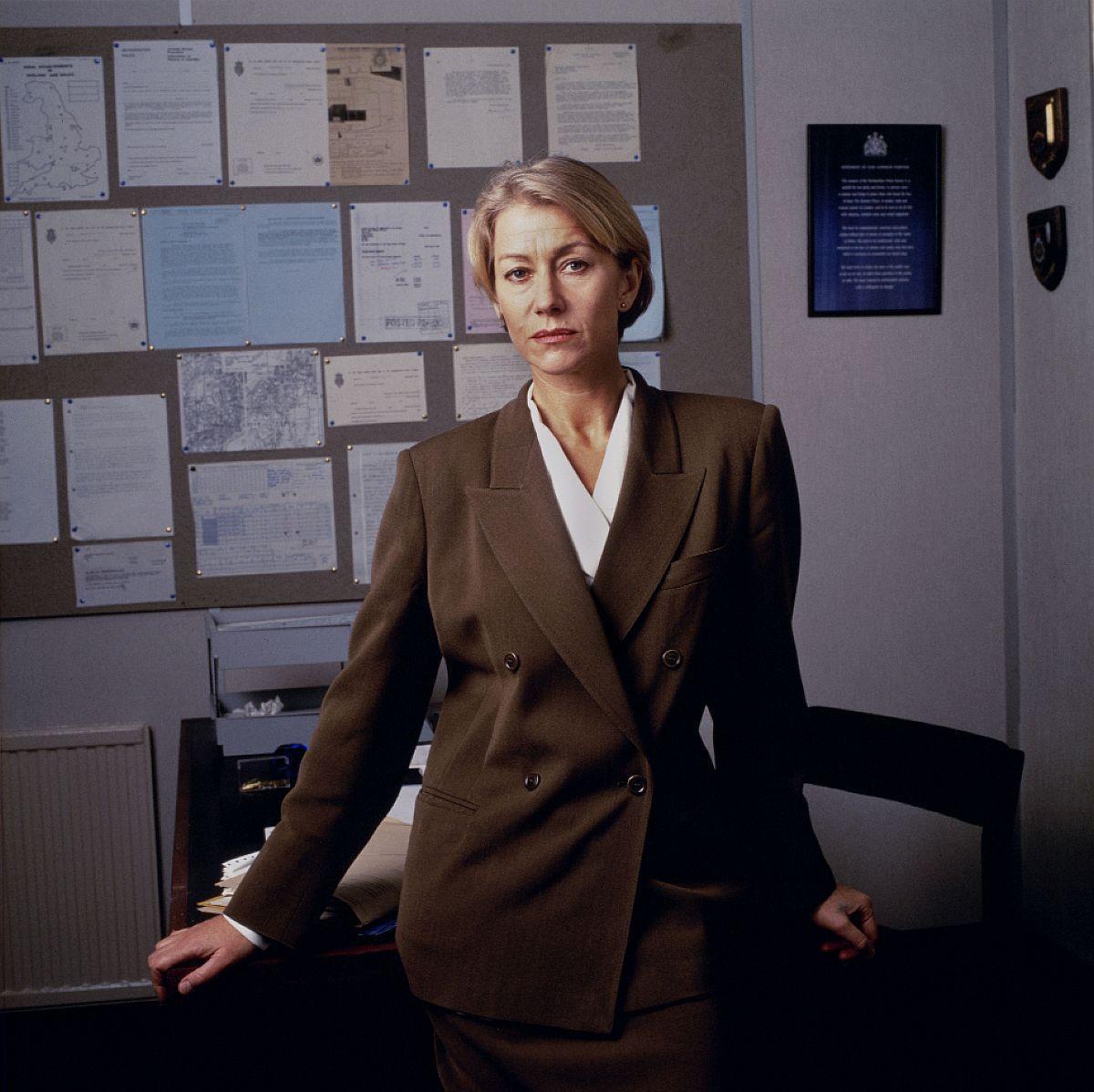

Actress Helen Mirren created an image of strong and formidable policewomen in her role as DCI Jane Tennison in Lynda La Plante’s television drama Prime Suspect. It was a massive hit show on ITV as viewers enjoyed Mirren’s pursuit of villains.

But back in 1914 women officers’ main duties were to deal with issues primarily related to women and children, such as rape, prostitution and homeless and lost children.

They did not have powers of arrest until later. Until the late 1970s they would have to leave the force if they had children.

Sussex Police deputy chief constable Olivia Pinkney, the highest ranking woman in the force, told the Argus she was grateful to women who stuck it out during that era and paved the way for other women.

But she said challenges remained even if the law and internal policy had moved on.

Speaking to The Argus ahead of the exhibition at the Police Cells Museum this week, she said: “You often see women self-limiting and holding themselves back.

“Now I am in a senior position I am really conscious of it and challenge myself and themselves not to self-limit.

“I think women still carry many roles, whether that is caring for elderly people, caring for parents, running the home – that falls more to the female in mixed gender relationships.”

Speaking of the impact of her gender on her own career, she added: “I have been conscious of it but it has never been a barrier. It has made me different some of the time but I am someone who puts great expectation on myself anyway, and just never felt it to be a barrier.”

She said it was important to encourage more women to consider a career with the police.

She added: “It is not just about doing the right thing for women but the best thing for the service. If you are only fishing in half the pool so to speak then you are not always going to have the best people.”

‘I was fulfilling a childhood dream’

CASE STUDY 1:

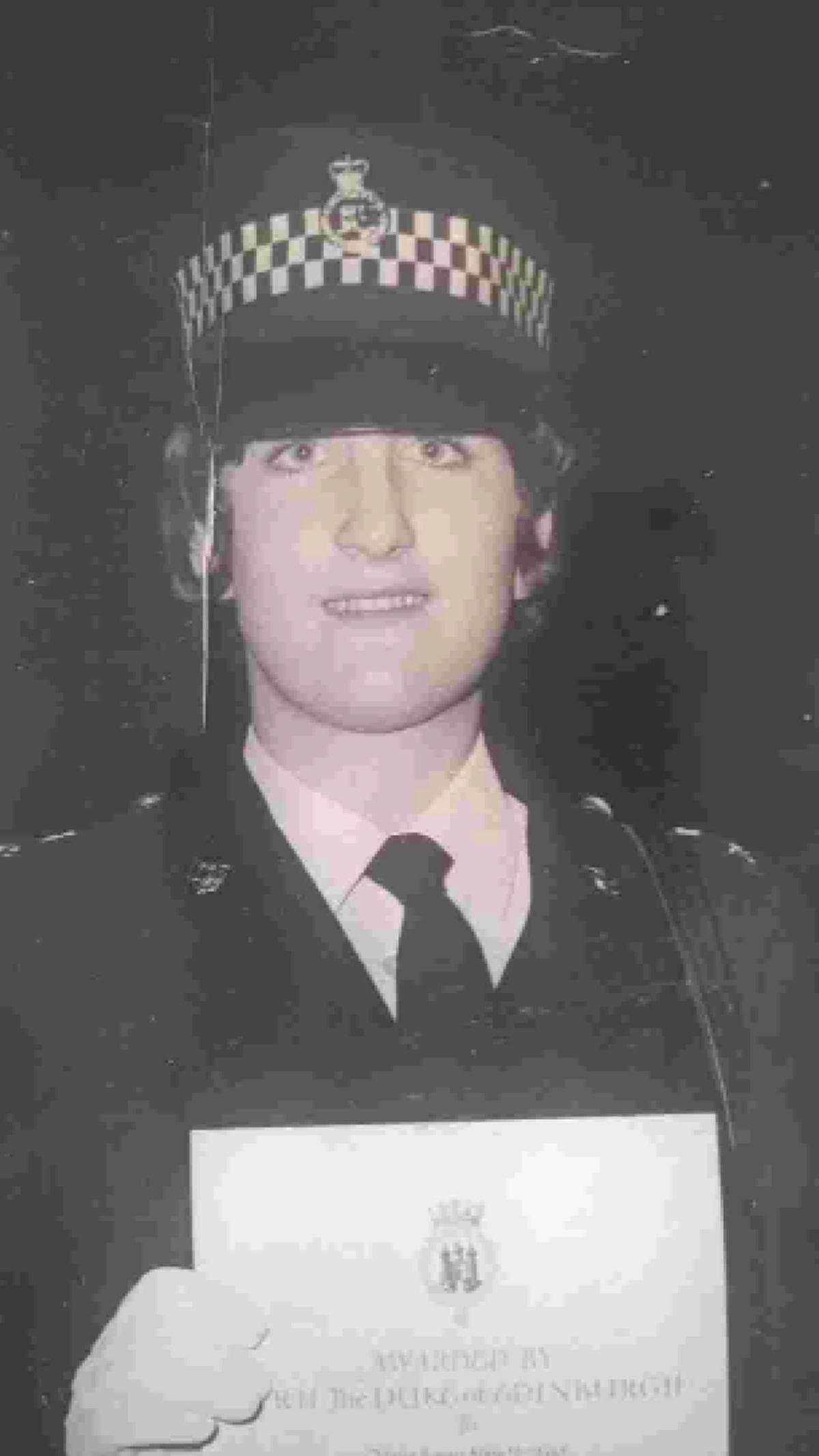

VERNA CANNAN knew from the age of ten that she wanted to be a policewoman.

She joined the Sussex Cadets in 1969 and went on to fulfil her dream in an era when women were consigned to a department (the women’s police department) that focused on working with families and children.

“We just accepted it,” she recalled, “but then to be honest we did not do the man’s work, we were not out doing the nights.”

As equality advanced that unit was disbanded and she said she wanted to be a detective. But her male superior had other ideas.

She recalled: “I said I wanted to be a detective and the DCI said ‘There will never be a womon detective in my department as long as I am in charge’. He was one of the old school.

“It was a totally different world - not just from the police but I think the whole society in the 1970s was different for anybody.”

His words made her more determined though. She became a detective in 1982, remaining in the role for the rest of her service.

“He said he had to reluctantly give me the job,” she said. “I think I was the only policewoman detective in the division at the time.

“It was alright, I think if you pull your weight and are part of the team, I think you are accepted.”

Detective Cannan was 37 when she had her first child, a daughter, in 1990.

By that time, things had moved on and, unlike many of her predecessors, she did not have to leave the force.

“I had a fabulous career,” she recalled. “I feel really blessed.”

She went on to work in several departments including as a family liaison officer and dealing with sexual offenders, working on the notorious Werewolf rapist case in the 1980s. She recalled: “There was a man travelling around Sussex breaking into elderly people’s bungalows and raping the women. I was heavily involved in that.

“I met with all the victims and took the statements so that was quite harrowing. There were good jobs and bad jobs.

“Certainly we got used to the idea that men could talk to female rape victims and I could talk to male rape victims. I think it depends on the victim.”

The retired detective now lives in Crawley and is in touch with former colleagues. She added: “It is a job where comradeship is key, you have to trust people you are in life threatening situations with.”

CASE STUDY 2:

RENATE HARRIS, 61, says her gender started to shape her career from a young age. When Renate went to a careers fair in Devon aged 16, she was told the area did not accept female cadets.

So she quickly moved to the relatively forward-thinking Sussex, working as a cadet for two years before joining the women’s police department in Horsham. She recalled: “I think policewomen at that time, they did not work shifts, they did not work later than midnight at that time and that was just the way it was I suppose – you are a woman, you needed to be mollycoddled.

“In Horsham I was allowed out on patrol because it was a quiet station.

“People would say, ‘I don’t often see a police woman walking around’.”

But even if women were restricted from some dangerous duties, there were others for which they were well-suited.

She said: “If you got a report of someone in the park exposing themselves you would go in plain clothes so that they would expose themselves to you.

“I remember when I was still a cadet we were used as bait because if women were being exposed to then they needed to catch them.”

Women started doing the same work as men in the late 1970s, and she remembers an interesting working life including stints in Brighton and Shoreham.

She added: “Yes there was bloke talk but actually I did not mind.

“They would say, ‘Oh look, we have got a WPC on for today, are you alright for tea, put the kettle on?’ But it was not nasty.

“I did not feel any of that but I am aware that some girls felt that there was some bullying.”

Renate married a fellow police officer and, as required at the time, left the force when she had her first daughter, even if she still needed to find part-time work.

She said: “As soon as I had my first daughter I took on some part-time work in a shop.

“It was work and it helped pay the bills of course – if you have job satisfaction then you are lucky.”

Things had changed when she rejoined the force in 1990 – even if not entirely.

She recalled: “I had to go back and have an interview and I remember the superintendent that was doing the interview knew my husband.

“And he said to me ‘what does he think of you rejoining’ – and I said he was fully supportive – but of course he should not have been asking the question.”

Renate went on to have a varied career, including working in child protection, retiring in 2002.

She recalled: “I actually felt better equipped because I had children and I had more life experience so I felt more confident.

“The doors were open so you could go into whatever you liked.”

CASE STUDY 3:

JACKIE BISHOP, 65, also came to Sussex because her home county, Dorset, would not accept women cadets.

She worked as a cadet between 1967 and 1969 and then as a WPC until 1972.

“In the early days it was very much male-banter,” she recalled. “I have always been somebody who was quite strong and just took it as one of the lads and just got on with it.

“I was not one of those ‘oh you touched my bottom’; you know you joined that job and you got on with it.

“There was not equal pay, not equal anything, and it was right to have the equality act.”

Mrs Bishop left after getting into a relationship with a married superior, for which she said they were both “hounded”.

She added: “It was worse than being a criminal to be honest. He was disciplined because of his rank.

“We got married in 1974 and we were married for 40 years.

“I would have loved to have stayed there, it was the best job in the world.”

CASE STUDY 4:

CAROL JUNIPER worked as a nurse before deciding she wanted a career change, joining the police in 1960.

She recalled having opportunities and her computer skills being put to good use when she merged forces’ records.

At the beginning, she was one of about ten female officers in West Sussex and one of the first working alongside men.

“I was not really angered [by it],” she recalled. “That was society at the time and the woman’s place was in the home.

“I did everything. They did not necessarily want women there but you just put up with it.”

She recalled having good opportunities in her career, but sometimes coming across prejudice.

She said: “If you had a problem no-one was going to believe the woman - it was the woman who was in the wrong.

“I went to a plane crash and they would give us the job of sorting out the bodies, thinking you are not going to be able to cope with it.

“They forgot some of us had been nurses.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel