By now we’re all familiar with the Snowdogs that have become a fixture of Brighton life. Perhaps some people will be less aware of the Sussex background of the man who inspired the hounds, however.

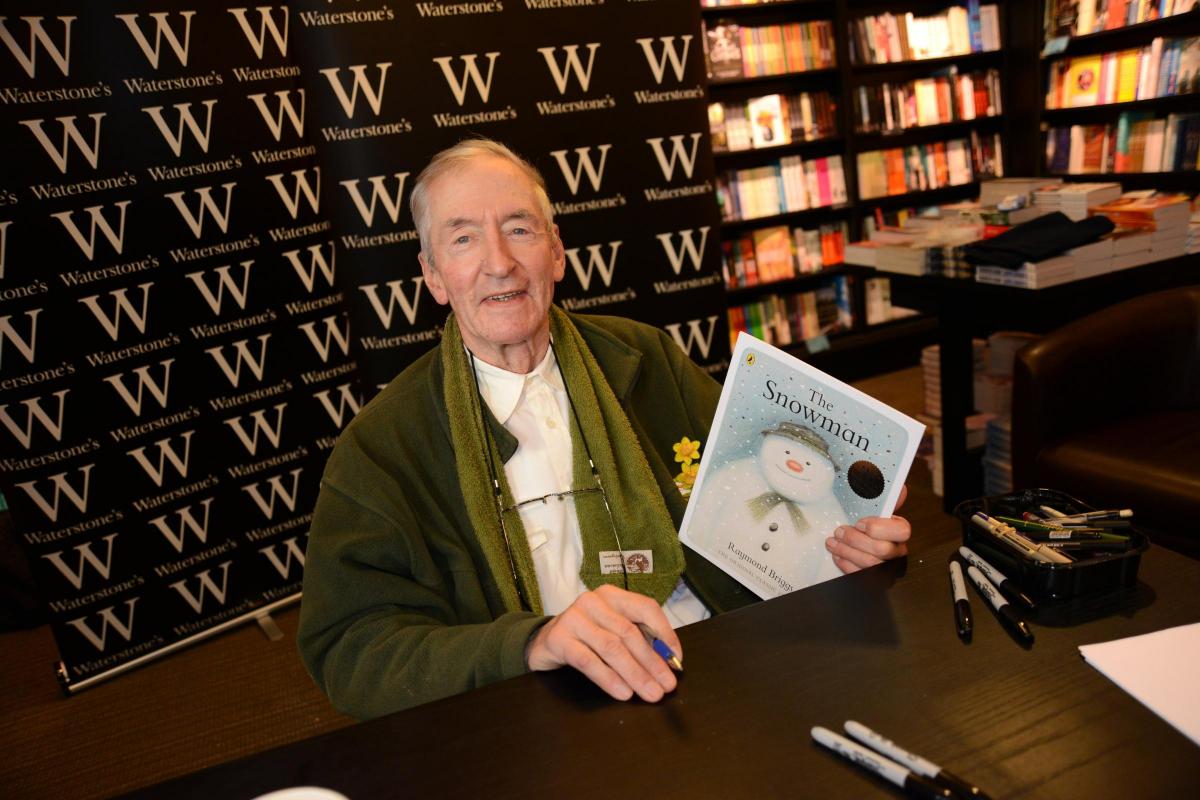

Writer and illustrator Raymond Briggs, whose classic book The Snowman was made into the animated film that preceded the 2012 animated sequel The Snowman and the Snowdog, has lived in the county for more than 50 years.

A new animated film based on another of Briggs’s graphic novels, about the life of his parents Ethel and Ernest, highlights the writer’s ties to Sussex.

There is a nice moment in the adaption where a middle-aged Briggs shows his parents his newly purchased Sussex cottage. “What a dump” is Ethel Briggs’ reaction, while Ernest is altogether more positive: “It’s the kind of place I’ve always dreamt of.”

Briggs, 82, moved into the house – which boasts scenic views of the South Downs – after taking a part-time job at Brighton College of Art - with his then wife Jean Taprell Clarke, who he married in 1963. Clarke, an artist, suffered from schizophrenia, or “brain trouble” as the animated Briggs calls it in the film.

At the very start of Ethel and Ernest, Briggs’s present home in the hamlet of Westmeston, near Plumpton, is shot in real footage with the writer at his desk as he wonders whether his parents would be happy with his portrayal of them.

Ethel and Ernest died within months of each other in 1971, after he had cared for her during her dementia. In a highly moving moment near the end of the film, Ethel asks Raymond “who that man was” at the hospital after Ernest exits.

Speaking after a warmly received screening of Ethel and Ernest at Duke’s at Komedia, Brighton, Briggs – who took on an executive producer role in the film and was heavily involved – said it was entirely director Roger Mainwood’s idea to film the first scene in Sussex.

The writer and illustrator has a reputation for being curmudgeonly but displayed a dry humour in an audience Q & A on Sunday. His answers were occasionally abrupt, but at other points he made light of his inability to remember his previous work and joked that Ethel and Ernest was “not bad, could be improved”.

“It was his (Mainwood’s) decision to have me in the film in the first place,” he said. “It is strange to have little railways for the cameras constructed in your own house.”

“We wanted to have Raymond in it to make people aware of where his story comes from,” added Mainwood.

As the animation kicks in after that first scene, the narrative rewinds back to 1920s London when Ernest Briggs (voiced by Jim Broadbent) first asked Ethel Bowyer (Brenda Blethyn) to the cinema when they had both finished work – he after his milkman rounds, she after her shift as a housemaid.

The couple had political differences; Ernest was a labour supporter who delighted in Clement Attlee coming into government after the Second World War, whereas the Winston Churchill-worshipping Ethel was a conservative.

The film, based on Briggs’ 1998 book, took nine years to complete. It interweaves world events such as the rise of Nazism, the Second World War and the moon landing with Ethel and Ernest’s personal life, including their courtship, marriage and bringing up Raymond.

The family’s large house in Wimbledon Park, London, in which Ethel and Ernest lived for 40 years, is so prominent that it feels like another character.

With 112 animators and 67,680 hand-drawn scenes, Mainwood was extremely thorough in his approach, calling on Briggs in his attempt to recreate the exact settings of his life.

“He was examining wallpaper and door latches,” said Briggs. “Everything was incredibly meticulous – maybe too meticulous, I thought.” An audience member had grown up in Wimbledon Park and personally vouched for the attention to detail displayed in the film. “Very good, that’s nice to hear” said Briggs upon receiving this man’s approval.

Briggs is happy to admit that his book is a story of “ordinary people”, but in the course of the narrative we become emotionally attached to his family. We fear for Ernest as he faces daily turmoil during his stint as an auxiliary fireman in The Blitz and feel Ethel’s humiliation when young Raymond is brought home in a police van after breaking into a golf club and stealing billiard cues.

“I don’t know why we took them,” said Briggs. “We were running around Wimbledon Park holding them like spears.”

Ethel and Ernest were classic products of their time, a couple forced to make the best of things as they construct air raid shelters and live with the daily threat of bombing. Post-war life was sometimes a strain, too, with rationing and austerity having an impact on everyday life. Briggs said that the depiction of his parents had touched a nerve with many people.

“I’ve had boxes of letters – handwritten letters from people doing ordinary jobs, saying that the characters are just like their mums and dads, or uncles and aunties.”

One of the most humorous strands in the film is Briggs’s parents’ bemusement at his burgeoning interest in art. At one stage Ernest enters the house to find his wife in tears on the stairs. Naturally, he fears that something terrible has happened.

“He says he wants to leave grammar school,” sobs Ethel, “and go to art school.”

While this ideological schism could perhaps have caused deeper ruptures between father and son, it is evident that Ethel and Ernest would have been proud of Raymond whatever he had chosen to do.

The concept of being an artist is just confusing to them in that age – Ethel constantly worries about the lack of money in it – just as the idea of homosexuality baffles them later in the film.

“They didn’t see my major stuff anyway (before they died)” said Briggs, referencing his classic graphic novels Fungus the Bogeyman (1977), The Snowman (1978), When the Wind Blows (1982) and Father Christmas (1991).

Briggs was fairly dismissive of the term “graphic novel” in general. “I don’t really like graphic novels and I don’t look at children’s books. I’ve just got to get on with my own stuff.”

He added that Ethel and Ernest was “still incredibly upsetting to watch” even after sitting through the entire production process. “You couldn’t have chosen anyone better than the voice actors. I was in tears the whole time because I thought my parents were sitting behind me. I won’t do that again.”

Briggs’s wife Liz died last year after a battle with Parkinson’s. Having lived a life which has contained much sadness, the last audience question asked how he has created art which possesses such humour.

“I didn’t know that – that’s good news” was his slightly uncomfortable response. A fitting last comment from the apparent curmudgeon who will be remembered for his warm, affecting work.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here