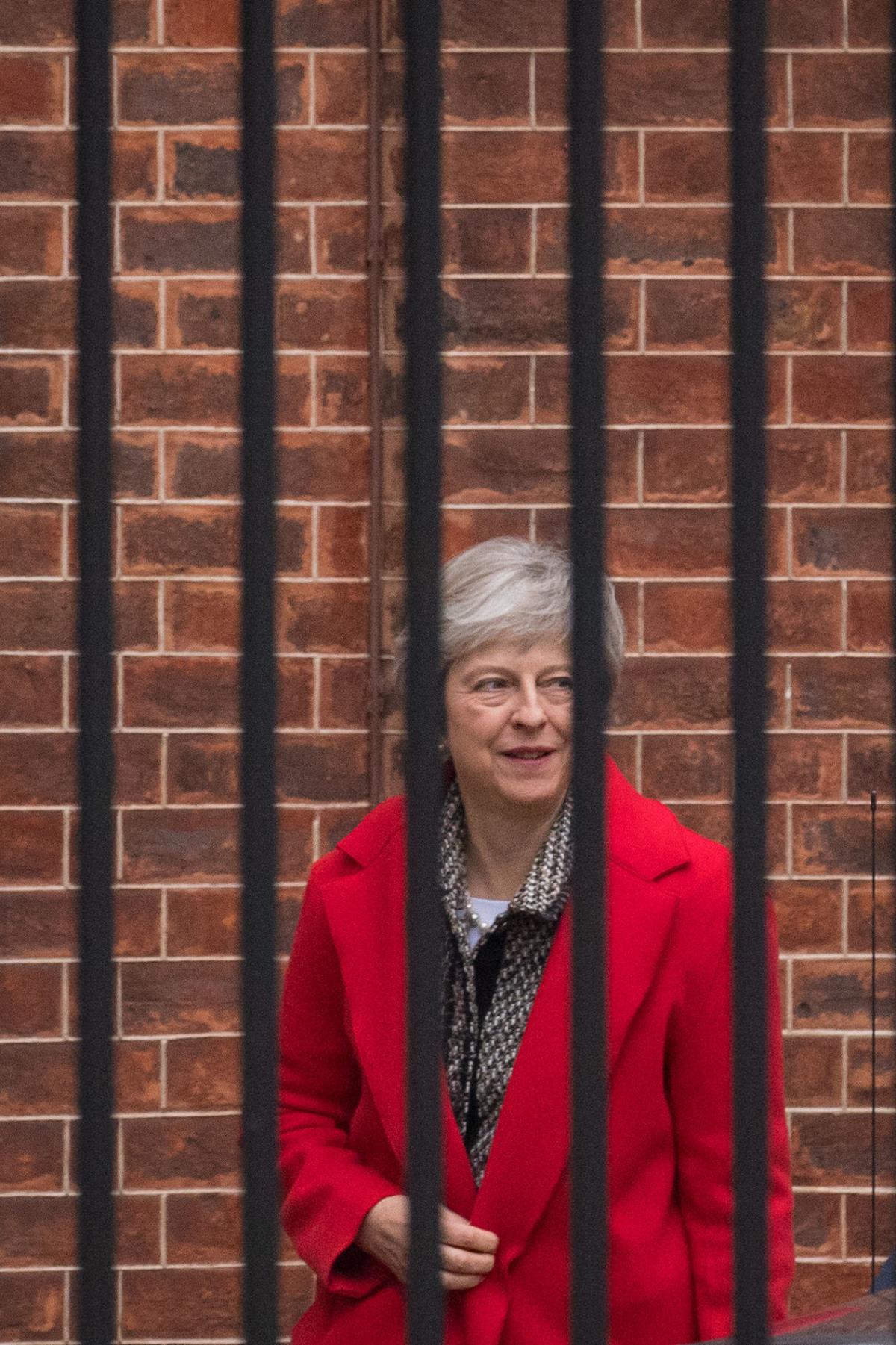

Mrs May has done well – given the cards she had to play.

She has come away with, probably, the least bad deal on offer and she just has to hope that Tory MPs come to vote on her leadership, as they might well do next week, they agree.

However, there was never – and can never be – a “good Brexit”.

Certainly, there cannot be one that betters our current deal which gives us opt outs from the Euro, from the border-free Schengen area and from the EU’s justice and home affairs laws.

In other words, we have a brilliant “pick and mix” version of membership of the European Union, and there was no way, that by leaving, we would be able to get anything like the same deal, particularly because for now we a full say in the decisions of the EU, but after March we still have to abide by their laws but without any say for the foreseeable future.

So Mrs May has come back with as good a deal as she could have reasonably expected to get.

But the problem she faces is that the Brexiteers promised a false prospectus and then came to believe it themselves.

Leaving aside the false promise about “£350 million a week going to the NHS” there were the promises that we would be “taking back control”, when in fact the reverse is the case; or that it would be a very simple matter to negotiate a new trade deal, when it has proved to be anything but the case.

It was nonsense then, and it’s nonsense now.

We have been part of the EU for 45 years – our laws, our trading arrangements, and much else besides, are deeply entwined within EU laws and regulations.

How could the Brexiteers possibly have believed that leaving would be simple?

After two years of painful, detailed negotiations we have only just arrived at the withdrawal agreement – and we haven’t even started negotiating our new trading relationship with the rest of Europe, let alone the rest of the world.

So, what are we left with?

The prospects of Mrs May’s deal being accepted by Parliament are virtually zero.

Labour, the SNP, the Liberal Democrats, as well as local Green MP, Caroline Lucas, will be voting against, as will a sizeable number of Tory MPs, both strong Remain supporters and the much larger group of “hard Brexiteers”.

What then?

First, there is the prospect of no deal – walking away with no agreements in place.

That, according to those much-derided experts (who happen to know a thing or two about the complexities of international trade) will turn most of Kent into a lorry park, as trucks heading for Dover and Folkestone queue up to clear the new customs arrangements, with similar queues on the other side of the channel.

The consequence will be shortages of food, medicine and other goods, and those factories that depend on “just-in-time” deliveries will be badly hit, as will international travel.

But the Brexit cliff edge can be avoided.

First, there could be, as Mrs May suggested outside Downing Street “no Brexit” – but that’s unlikely to happen.

The option currently being pursued by Labour is to call for a General Election – but that’s what oppositions always say.

Under the new five-year fixed term Parliament rule, there cannot be an election before 2020 unless two thirds of the House votes for one (as they did in 2017) or Mrs May loses a no confidence vote in Parliament.

Neither is likely to happen since there certainly wouldn’t be a two thirds majority for an election and, given that the Conservatives fear Mr Corbyn even more than they fear Brexit, a no confidence vote in the Government (as opposed to Mrs May) would rally virtually all Tory MPs (and the DUP) to the PM’s side.

Nor would replacing Mrs May with a different leader solve anything.

The Conservatives are between a rock and a hard place entirely of their own making, and Labour isn’t much better off.

There is only one escape route for both parties, and most importantly for the country – a People’s Vote because now that we know the terms of the deal we are in a much better decision to make an “informed” choice.

Back in 2016 we were promised that leaving the EU would be the answer to all our problems.

We now know that that isn’t the case, but if the country again votes to leave then at least that choice will have been made in full knowledge of the consequences.

Ivor Gaber is professor of political journalism at the University of Sussex and a former Westminster political correspondent

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel