Fiona Donnelly-Rheaume has contacted The Argus from her home in Yellowknife, Canada, to share her memories of the one of the worst rail disasters the country has ever seen, which happened at 1.39pm on a rainy Saturday in March 1989, killing five people and injuring 88.

“I remember the smiles, the courage and the last moments people shared laughing so loudly with their friends, a smile I gave to the lady across from me as she told me how proud she was of her daughter,” said Fiona.

She is originally from Motherwell in Scotland and lived in Norton Road, Hove, at the time.

Now married to Alain and the mother of a 24-year-old daughter Rosalie, Fiona has previously told The Argus how she was haunted by hallucinations and nightmares about the crash.

She lost her job, home and her fiancé in the six months afterwards and received treatment for psychological trauma for the following year.

“I’ve looked back at those things I said and they were pretty bleak,” said Fiona, who is completing her undergraduate degree in theatre at the University of Victoria in Victoria British Columbia.

“I wanted to let The Argus readers know that my life is really good, and I have been living in Canada being a mum, a wife and a friend, doing lots of theatre, which is what I love, and I try to live my life in gratitude rather than fear.”

She marked the anniversary on the university campus watching a performance of a scene she had directed from Jonathan Wilson’s 1998 play Kilt.

“I chose that date to be doing something alive, to remember living,” she said.

Fiona described how the “positivity of the lives around me” before the trains collided have stayed with her.

“When I see the beautifully stitched scar on my left shoulder, I remember that I was one of the lucky ones. The people sitting behind me and the sweet elderly lady opposite me died.”

Fiona was 22 and travelling in the first carriage of the Littlehampton train when the collision happened just outside Purley railway station in Croydon.

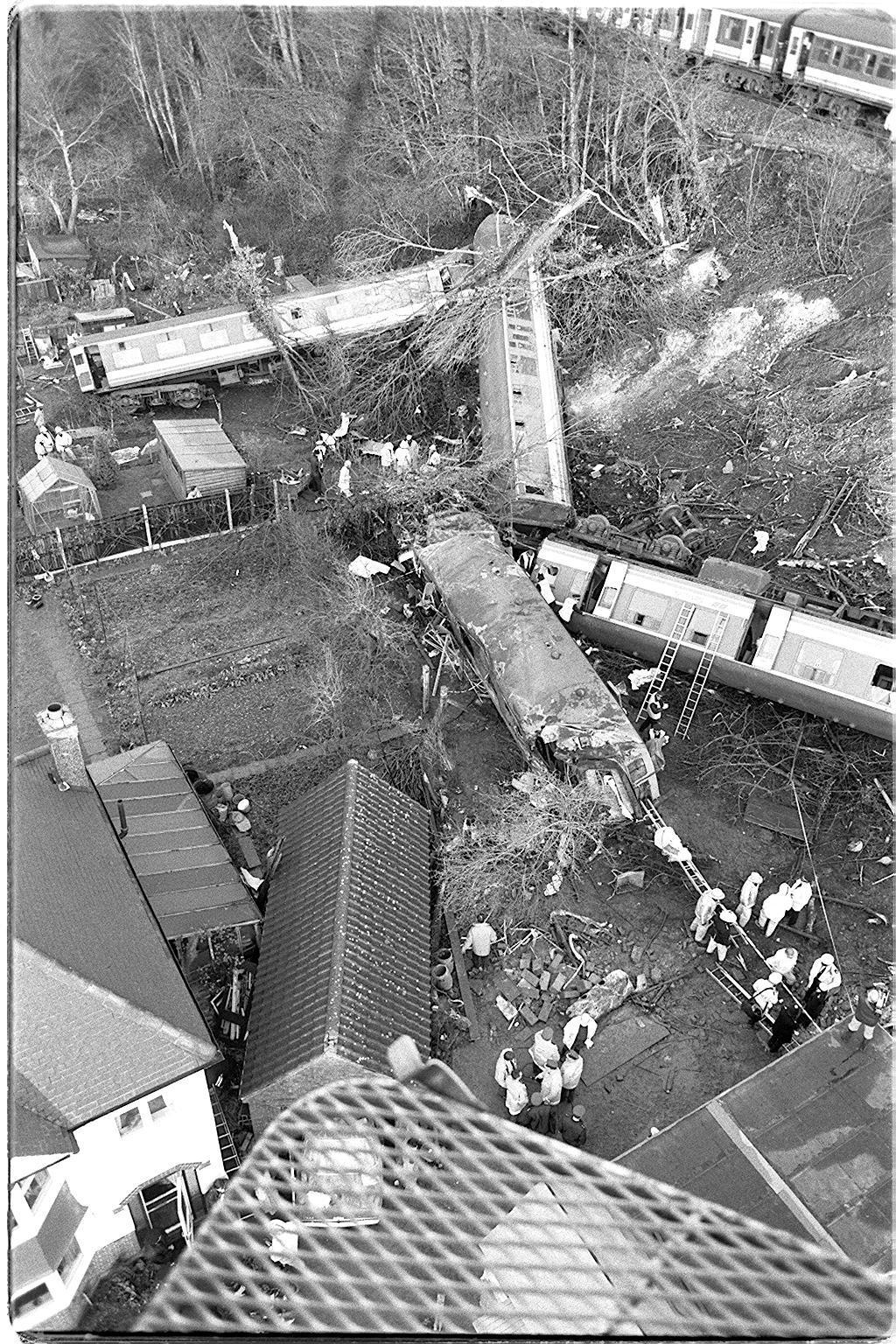

The first six coaches of the train careered down the 60ft embankment, coming to rest in the gardens of houses in a cul-de-sac, Glenn Avenue.

Residents rushed to the accident scene with ladders and tools to try to rescue passengers, some trapped for hours because the doors were blocked.

“The window frame of our carriage window lay around my knees like a mangled hula hoop, and just in front of me carriage seats lay propped up on random pieces of metal” said Fiona.

“I thought I was sitting in a rubbish heap.

“A huge tree was on its side, blocking any view to the right of me.

“I thought ‘I can’t die today – I have too much to do with my life, I’m not ready to go’.”

In front of her was a young man who had been in the same carriage as Fiona, her “guardian angel” who held her hands and whose smile she remembers.

Fiona could see only the legs of the woman who had been sitting opposite her because a huge piece of metal was on top of her.

“The people who had been laughing and chatting in the middle seats were quiet now,” she said.

“It seemed so wrong.”

Fiona does not remember how she got out of the carriage but she made her way through a garden to a house and was then taken to hospital.

She couldn’t move for days, her body “a yellow green curry soup of bruises”.

After the crash, which happened just weeks after the Clapham rail disaster in south London, killing 35 people, train driver Robert Morgan, from Ferring, pleaded guilty to two counts of manslaughter in 1990.

But in 2007, his conviction was quashed at the Court of Appeal when it transpired there had been problems with the

signal prior to the crash and other trains had also gone through the red light.

At the memorial marking the first anniversary of the crash, Fiona talked to a woman she now realises was the daughter of the woman sitting opposite her on the train and who had died.

“She graciously told me she was happy I got to live,” she said.

“Her mum had been talking about her that day and how proud she was that her daughter was playing with the Royal Symphony Orchestra.

“I always wanted her daughter to know that her mum was smiling and talking about her daughter seconds before the crash, that her last thoughts were of her daughter.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel