JOHN “Jack” Galyer is best remembered as a respected teacher.

A pillar of his community, Jack was loved and feared by his pupils at Moulsecoomb Junior School in Brighton.

One ex-pupil, Paul Clarkson, said he was “scared to death of him”.

“I remember the day when they announced the currency was changing to the decimal system, he threw his paper across the room. I was always afraid of him,” said Paul, 62.

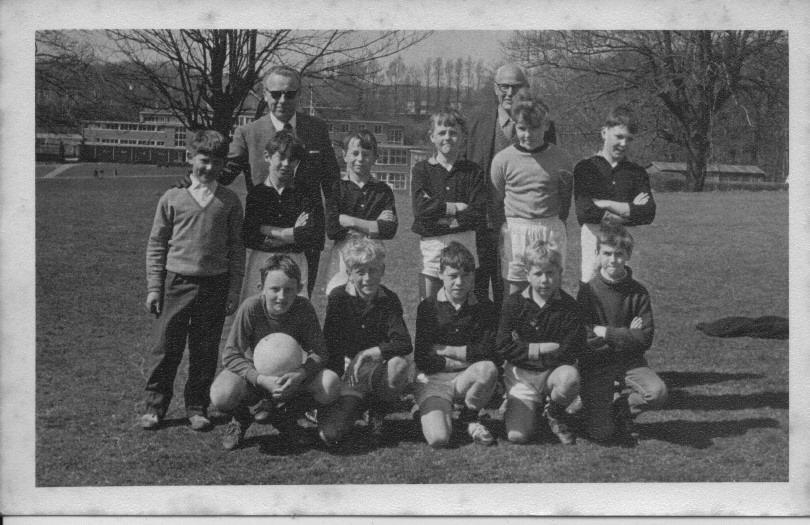

Despite his authoritative nature, Jack cared deeply about the football and chess clubs he ran and loved to unwind with a round of golf after school.

So when amateur historian Paul found out his old teacher had been a prisoner of war in a brutal Nazi camp, he was shocked.

Tragedy struck early for Jack, who was born in 1920 – his father John died when Jack was only 14.

Then at the age of 20, while studying to become an electrical engineer, Jack was called up to the RAF. After training in Winnipeg, Canada, he was sent to the South African Air Force and had to fly the highly dangerous Takoradi Route, a 2,400-mile non-stop flight from Lagos in Nigeria to Cairo, Egypt.

Such a long route required lots of fuel, so the Hurricane fighters Jack flew were strapped with extra tanks that made the plane a bigger target.

In October 1942, daring Jack’s luck ran out when he was shot down over North Africa and sent to Stalag Luft III, the brutal German POW camp featured in the classic film The Great Escape.

Jane Stewart, Jack’s daughter, said he was almost part of the famous failed escape in March 1944 and was caught down one of the tunnels.

“Fifty officers were shot because of their attempted escape. Dad remembered being in the cooler several times,” she said.

“He wasn’t alone in feeling guilty about being shot down and not being able to help with the war effort.

“Everyone back in Moulsecoomb heard the news of boys who hadn’t made it or had become prisoners of war and they would pray for them.”

But the worst was yet to come for Jack, despite his spells in solitary confinement.

With the Soviet Red Army drawing near, the Nazis evacuated Stalag Luft III, forcing the inmates to march 100km to Spremberg in freezing conditions where they were stuffed into a cattle train and taken to Westertimke.

From there Jack and his fellow prisoners were marched another 100km to Lübeck, where they arrived in May – just days before they were liberated.

Jane, 66, joked: “No wonder Jack never wanted to go on any adventurous walking holidays.”

Though he was unimpressed on returning to civilian life, Jack quickly fell in love in with future wife Joan Riches and married her on October 9 1945 – exactly three years since he had been captured in North Africa.

Naturally, Jack joked he had been captured twice in his life.

“After being given some second-hand golf clubs he decided he would work at a job that would allow him plenty of time off so he could enjoy his new love,” said daughter Jane, who now lives in Australia.

Jack then trained to be a teacher and happily secured a job at Moulsecoomb Junior School, where he ferried the football team to matches in his yellow Ford Anglia.

“He drove that poor thing into the ground,” said Jane. He was fortunate that the house they bought in Hollingbury was at the end of a group so he was able to build a garage to house his ‘beauties’.”

Ultimately, Jack is remembered as a man who loved his pupils. He took great pleasure in teaching them, especially the sporting side of schooling,” said Jane.

After retiring, Jack and Joan joined their daughter in Australia in 1988, where Jack continued his golfing obsession until his death in 2005 and Joan, 96, still resides.

But despite his move, Jack’s influence is still felt in Moulsecoomb. “Recently I spoke to someone who remembered his car registration number,” said Paul. “People don’t do that if they don’t respect him.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel