“EVERYBODY was ready to pay for freedom with their lives.”

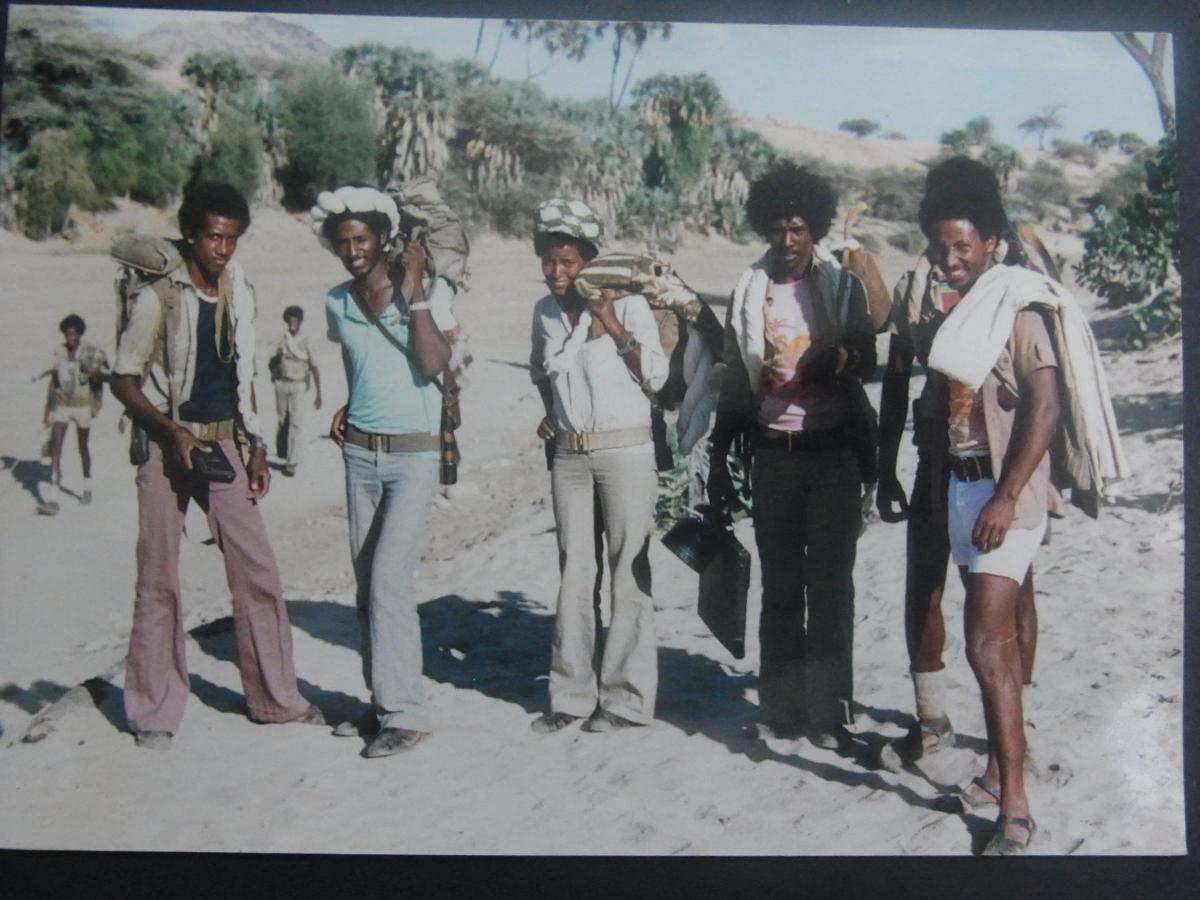

When Mebrak Ghebreweldi joined the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front as a teenager in 1978, she knew what she was in for.

Her home country of Eritrea was then under the control of a cruel military dictatorship known as the Derg, which also ruled Ethiopia.

Though the 55-year-old is now sitting in the office of her Lewes translation firm Vandu, it is clear what motivated her to become a rebel will stay with her for ever.

“When I was young, my uncle went to sharpen his ploughing tools and as he was crossing the road all of these big trucks were passing by,” she said.

“He started crossing and they just shot him in the middle of the road.

“His body was found three days later, by the wheat fields. I just couldn’t make sense of it.

“Why would they kill somebody crossing the road with a hoe on their shoulder with so many bullets?”

By this time, Mebrak and her family had run away from their home to hide.

But as the violence continued, tragedy continued to strike for Mebrak.

Another uncle was killed in the capital city of Asmara, then another was shot ploughing his own land.

Even her big brother, a young teacher, had been arrested by the government.

So Mebrak became a rebel.

“Women weren’t just soldiers, we were trained in everything from medicine to communications,” she said.

“You didn’t just pick up a Kalashnikov, you learnt to apply dressings and bandages, because if someone got hurt and a doctor wasn’t there, it was up to you.

“But mainly I was a radio operator.”

Was she ever scared?

“Never,” Mebrak said.

“When you’re a young person and you see others with the same values and beliefs, you’re quite liberated from fear.

“That’s what we were all like when we were young.

“We didn’t want people to be killed on their land, we didn’t want people to die on the streets.

“We would rather die ourselves and put an end to that once and for all. It makes me feel emotional still.

“I have two boys and sometimes I think ‘what happened to this generation?’. Why can’t they see when things are unfair?

“But my friends say they do rebel, just in different ways.

“You don’t have to pick up a gun to be a rebel.”

Crucially, as a Morse code operator for the front, Mebrak learnt the importance of communication.

That was something which drove her to found her translation firm in 1999, eight years after Eritrea gained its independence.

“In war, communication can create peace,” she said.

“In peace, communication can create harmony.

“There is no positive outcome when people are divided. The moment you treat someone with respect and talk to them, something good will happen.”

A year after the war’s end in 1991, Mebrak moved to London to study business and computing.

Originally she wanted to return to Eritrea with her skills.

But after becoming a single mother at university, she decided to stay in the country for her boys Joshua and Aaron.

When she finished her Master’s degree in 1999, she was at a crossroads.

“I wasn’t sure what to do, but I didn’t want to just do nothing,” she said.

“I had fought for equality and here I found myself with boys younger than five struggling to get by.

“I decided to start a translation firm from my dining room. I worked almost 24 hours a day.

“I’d get up, take the kids to school, work, get them back, maybe take them out swimming and still be working by 3am.

“The first few months were very hard, but after six months I had more than 30 linguists covering 16 languages. I was doing everything else.”

Vandu now has more than 1,500 translators helping train migrants and refugees to become interpreters themselves.

Mebrak still remembers her proudest moment.

“After about ten months I was earning enough to not need housing benefit,” she said.

“I felt so proud to go to the office and say ‘I don’t need this any more, thank you’. The woman couldn’t believe that I had been there crying ten months ago.”

But Vandu is by no means an industry giant – and that is something Mebrak is proud of.

“Once a business adviser came in and was surprised we weren’t earning a million pounds. I never did this for turnover,” she said.

“I do it for the people who train with us, become interpreters and go out into the world.

“One of my translators helped a man from the Middle East who came here as a refugee in 2003.

“In 2008 she got on a bus in Brighton and she heard “Hello madam”. He was the bus driver.

“When you’re in this business, there’s nothing better than seeing someone succeed.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here