WHEN Edward Bransfield died in 1852, nobody knew who he really was.

Having lived in Brighton for the last five years of his life, the merchant sailor was buried in Extra-Mural Cemetery at the age of 67.

It was a modest end to the man who discovered Antarctica.

The question of why Mr Bransfield faded from history is as puzzling as the mystery which surrounded the continent before his voyage there in 1820.

“He didn’t write a book about his exploits. He didn’t give any interviews,” said polar historian Michael Smith.

“We don’t even know what he looked like.

“When he returned from Antarctica after discovering it, nobody really cared. It was a hostile frozen world with no business or trade opportunities, so he was pushed to the sidelines of history.”

In fact, the adventurer’s life began as obscurely as it ended.

Born in the small Irish village of Ballinacurra in 1785, Mr Bransfield was forced into the Royal Navy at 18 years old.

Unlike many of the young men pressured into the Napoleonic Wars, he excelled as a sailor.

“Most press-ganged sailors would have been cannon fodder, but Edward was a bit different,” said historian Mr Smith

“He was a ship master responsible for navigation, which is a pretty big responsibility.”

Having survived the Napoleonic Wars, Mr Bransfield was posted to Valparaiso in Chile to serve in the Navy’s Pacific Squadron.

It was there he met merchant sailor William Smith, who had made an unintended discovery.

While sailing off South America, Mr Smith had been driven south by strong winds and spotted unknown mountains.

Hearing the news in Valparaiso, Royal Navy Captain William Shirreff chartered Mr Smith’s ship “Williams” and tasked Mr Bransfield to investigate.

Setting off south in 1820, the captain and his crew again encountered the mountains.

Landing on the largest of the South Shetlands, as they came to be known, he claimed it for King George III, who had died the day before.

Perhaps sensing he was going to make a great discovery, Mr Bransfield decided to push further south.

“He was sailing into some of the most violent seas with choppy waves,” said biographer Mr Smith. “He wasn’t in a military ship either, just a small brig.”

On the same day he spotted the Trinity Peninsula, the northernmost point of Antarctica, becoming the first ever person to do so.

After returning to Valparaiso and handing his maps to the Navy, Mr Bransfield may have expected a hero’s welcome.

But instead he travelled home to become a merchant, eventually settling in Brighton’s Clifton Road in 1847.

When he died in his London Road home five years later, he had little wealth to his name.

But that is what makes him so enigmatic.

“He was a loyal Navy man,” said Mr Smith

“So maybe he thought if the Navy did not care about his discovery, he should not either. But he kickstarted Antarctic exploration. He’s the reason scientists are able to study global warming in Antarctica. He should be remembered.”

For a long time the only mark Mr Bransfield left on the world was the Bransfield Strait, the choppy sea where he made his discovery.

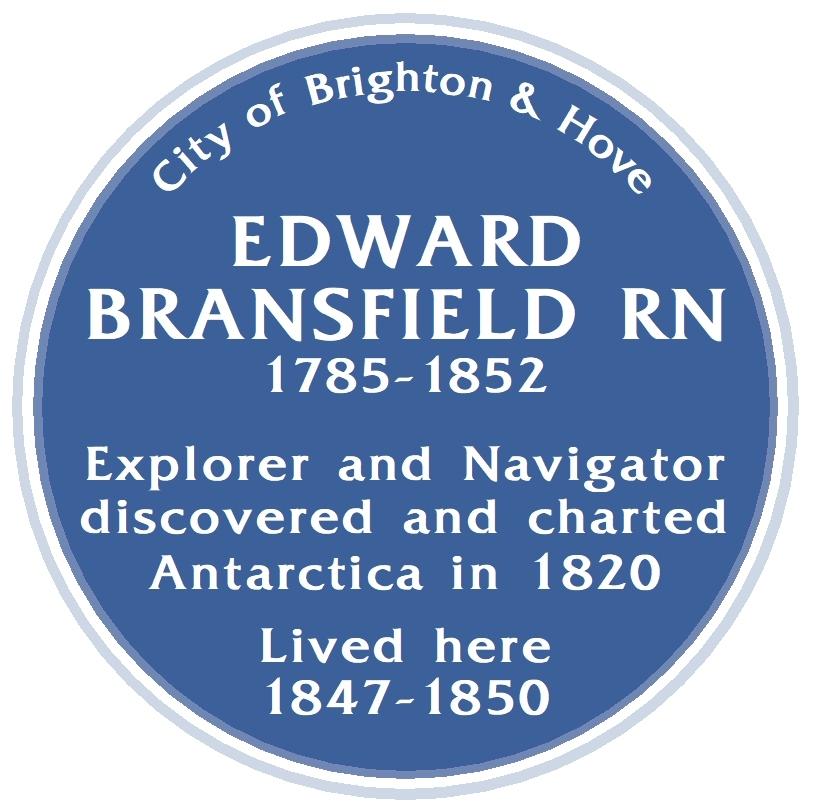

Yesterday a blue plaque has been placed on his Clifton Road home to remember his quiet time in Brighton.

Not much more is known about the sailor, and it is likely not much more will be.

But what would historians want to know if they could?

“I would love to see a photograph of him,” Michael said.

“And I’d like to take him down the pub and chat about his exploits.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here