IT ALL came about quite quickly.

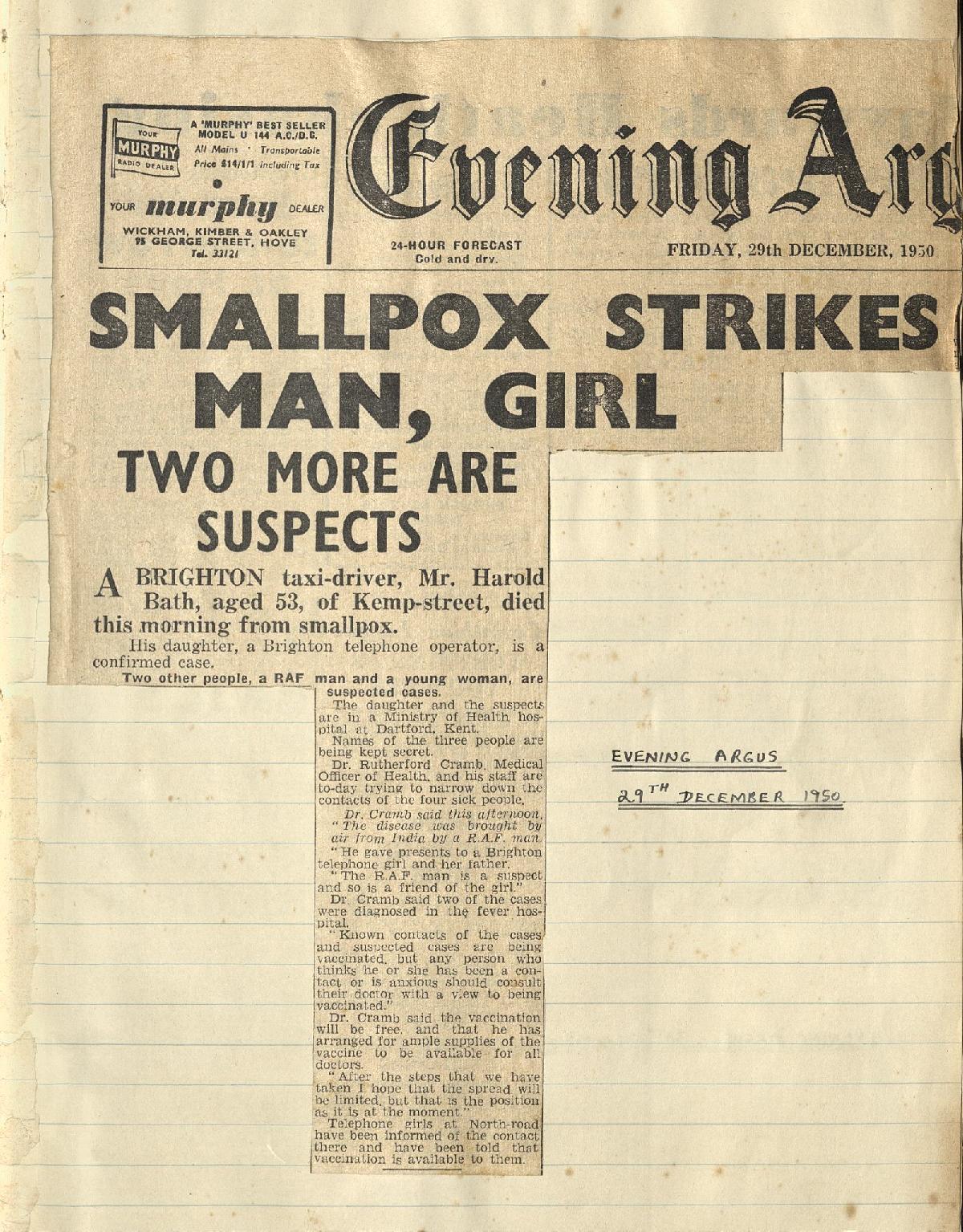

Christmas in 1950 had barely passed when, on December 29, a horror story splashed across Brighton’s front pages.

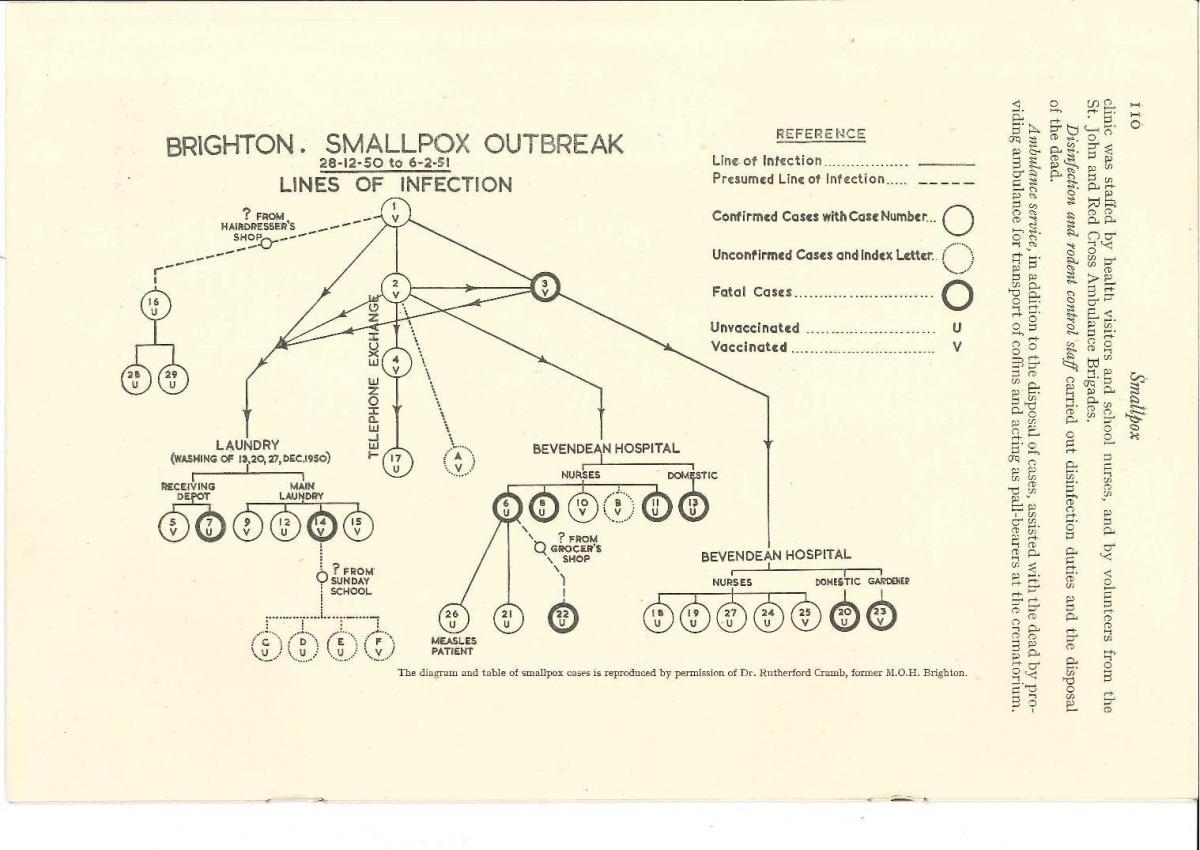

Taxi driver Harold Bath, 53, had died of smallpox in Bevendean Isolation Hospital.

His daughter, telephone operator Elsie, was also diagnosed with the disease and sent to Dartford Isolation Hospital in Kent alongside two other suspected cases.

The family had caught the bug from an RAF officer who had flown back from Karachi, India, to spend Christmas with the Baths.

As an Evening Argus reporter later put it, the biggest manhunt Sussex had ever known had begun.

At the peak of the outbreak 19 men working 13-hour days were engaged in a ruthless search to find anyone who so much as glanced at someone with smallpox.

By the next day, 300 workers at the Brighton Telephone Exchange had been vaccinated and their social functions were cancelled.

But the newspapers pleaded for calm.

“The outbreak of smallpox in Brighton is disquieting but there is no cause for alarm,” The Argus wrote.

“Any irresponsible rumour-spreading could do great harm.”

“Such an outbreak is just one of those accidents which are bound to occur as a result of the development of air travel,” the Sussex Daily News reasoned.

“One can bring a disease to this country before any infection has had time to develop.”

With five cases in the city confirmed, Brighton’s chief medical officer Dr Rutherford Cramb had seen an outbreak coming.

The 65-year-old Scotsman had written a frustrated report the year before raising concerns over a lack of parents vaccinating their children.

Now he had to tackle what he had feared.

“It’s the worst Hogmanay I have ever known,” he later quipped to the papers.

But the First World War veteran seemed to inspire confidence in others.

“A dapper Scotsman of 65, Dr Cramb looks much younger,” the Evening News wrote.

“His manner reveals a quick sense of the incident.”

The doctor’s first priority was vaccinations.

On New Year’s Day 1951 200 people lined up outside the Royal York buildings to be vaccinated at an emergency centre there.

By the following evening, 10,000 people had been injected thanks to an emergency train loaded with vaccines from London.

Vaccine mania struck Brighton. After one particularly busy day at a doctor’s surgery, a Ministry of Health official described those waiting as a “seething mob”.

“We haven’t the faintest idea how many we have used,” he added.

The Argus reported on patient 92-year-old Rose Davis who had diligently waited for an hour to be vaccinated.

Some claimed doctors were profiting from the outbreak by charging five shillings for a vaccination.

But one told the Brighton Standard “I was far too busy vaccinating people to worry. about making out returns.”

One doctor who had gone hoarse from calling patients’ names had a record made of his voice to play in the waiting room.

As tends to happen in the face of danger, Brighton residents pulled together.

“’Been vaccinated yet?’” The Argus asked.

“It’s the topic of the fish queue and the 8.25.

“It’s the burning question on the golf course, over the snooker table, and during the lulls at bridge night.”

But though spirits were high in Brighton, as the number of infected rose to its peak of 29 rumours began to affect business.

Theatre attendances were crippled by whispers of audience members taken ill.

On one particularly bad night, one comedian implored the sparse crowd to move to the front rows to make things “matey”.

Rumours persisted patients were escaping quarantine at Bevendean Isolation Hospital by leaping over the wall.

But this was dispelled when it turned out the perpetrators were the Holmwood brothers who lived in a cottage on the hospital grounds.

“It’s been a little race since we were going to school,” said 30-year-old George.

Then again, the small bouts of panic did help some.

One wine seller told the Evening Argus bankers in London had extended his credit because they were scared of getting infected by his cheques.

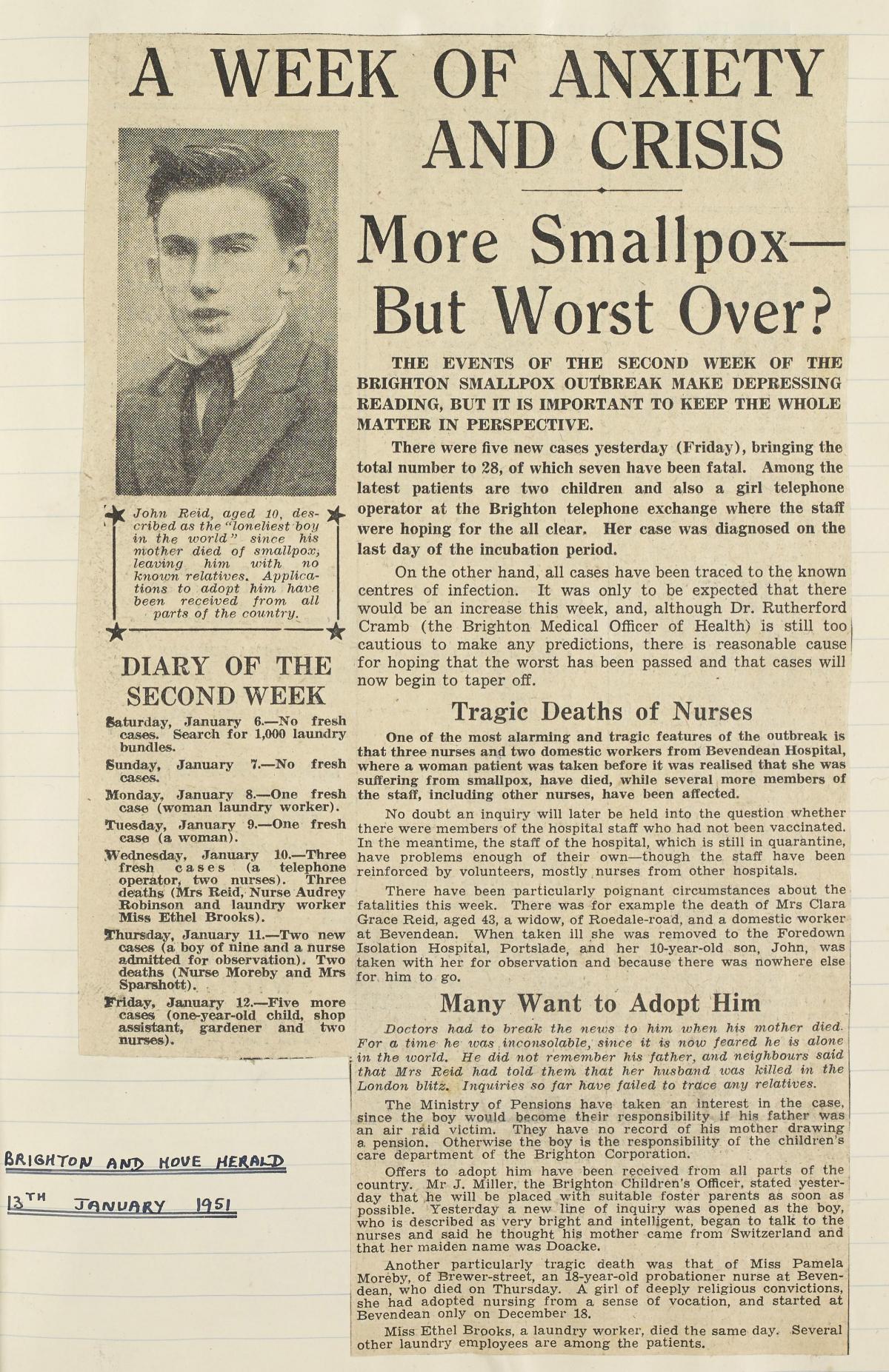

Though the death toll was impressively capped at ten by the end of the outbreak, it did not make the loss of life any less tragic.

On January 13 newspapers told the sad story of “loneliest boy in the world” ten-year-old John Reid, whose mother Clare died in a Portslade hospital.

“We want to find a new home for him quickly so that his life is disturbed as little as possible,” said Brighton children’s officer J Miller.

But by February 1 it was clear the outbreak was coming to an end.

The quarantine at Bevendean Isolation Hospital was lifted and nurses were given a 14-day paid holiday.

“We are glad to be free again but we haven’t really been bored,” said 23-year-old Molly Deasey.

“There was too much to do at first.

“We organised concerts, saw films, had whist drives and table tennis competitions.”

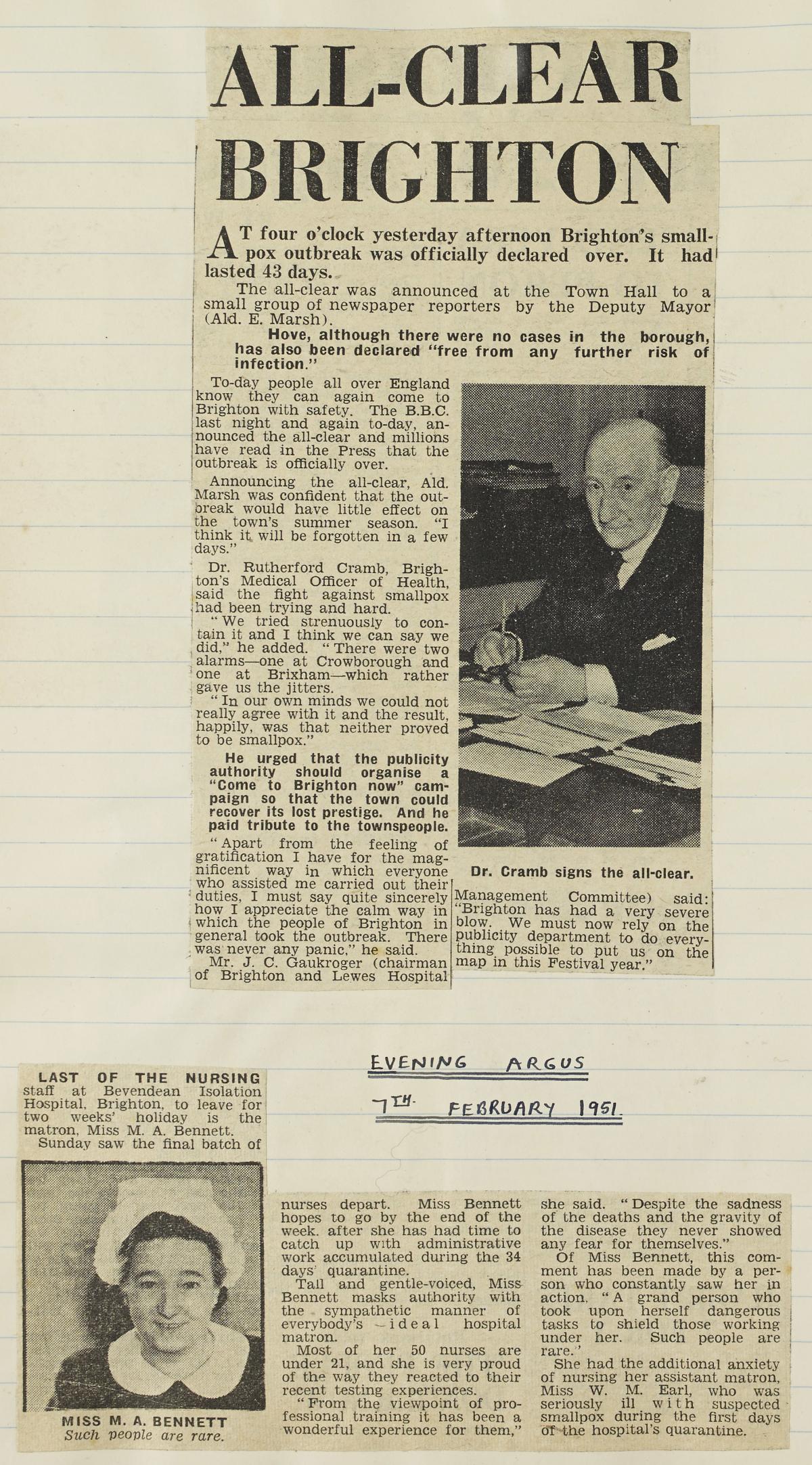

Six days later, deputy mayor E Marsh gave Brighton the all-clear.

Dr Cramb was proud but admitted two scares outside Brighton had given medics “the jitters”.

“We tried strenuously to contain it and I think we can say we did.”

But typically no one had thought to tell poor old Hove the outbreak was over and an emergency briefing was put together in half an hour.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel