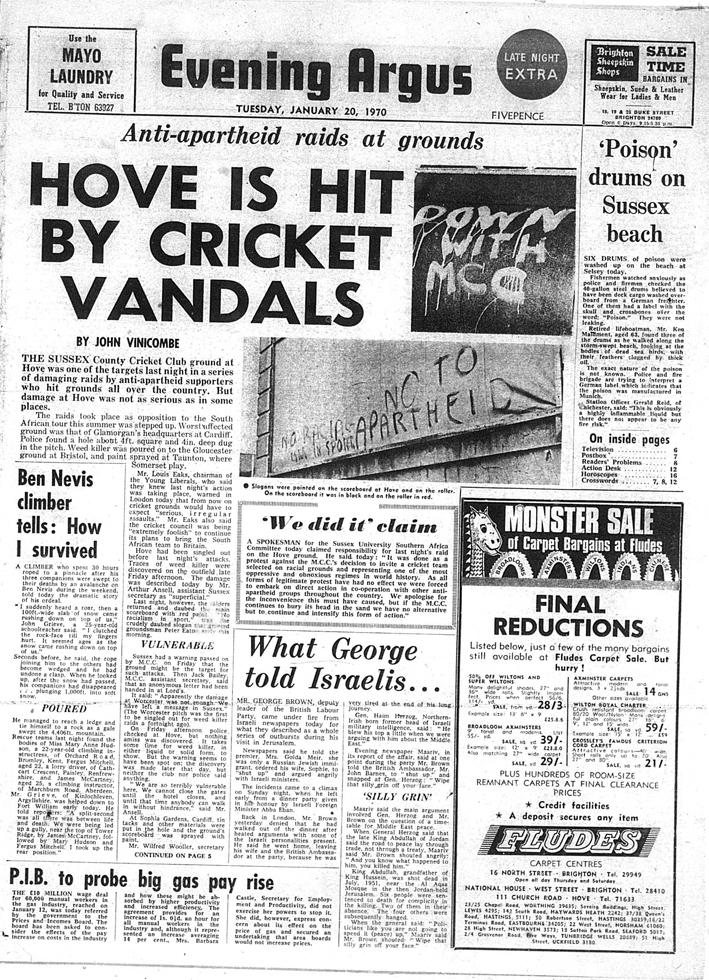

WHEN Sussex Cricket Club groundsman Peter Eaton arrived at the County Cricket Ground in Hove early on January 20 1970, he was in for a shock.

“No racialism in sport, no to apartheid” read the slogan daubed in red on the scoreboard.

“Down with Marylebone Cricket Club,” yelled another slogan painted on the ground’s roller.

The “crude” vandalism, as The Evening Argus described it, was received with shock.

Sussex’s assistant secretary Arthur Ansell said the club was vulnerable to further attacks.

“We cannot close the gates until the hotel closes and until that time anybody can walk in here without hindrance,” he told The Evening Argus.

But for the Sussex University Southern Africa Committee the overnight break-in was a job well done.

The student group was one of a number across the country protesting against the upcoming South African cricket tour of Britain.

“It was done as a protest against the MCC’s decision to invite a cricket team selected on racial grounds and representing one of the most oppressive and obnoxious regimes in world history,” a spokesman told The Argus.

Though the vandalism came as a shock, action against South Africa’s apartheid regime had been ramped up in recent years.

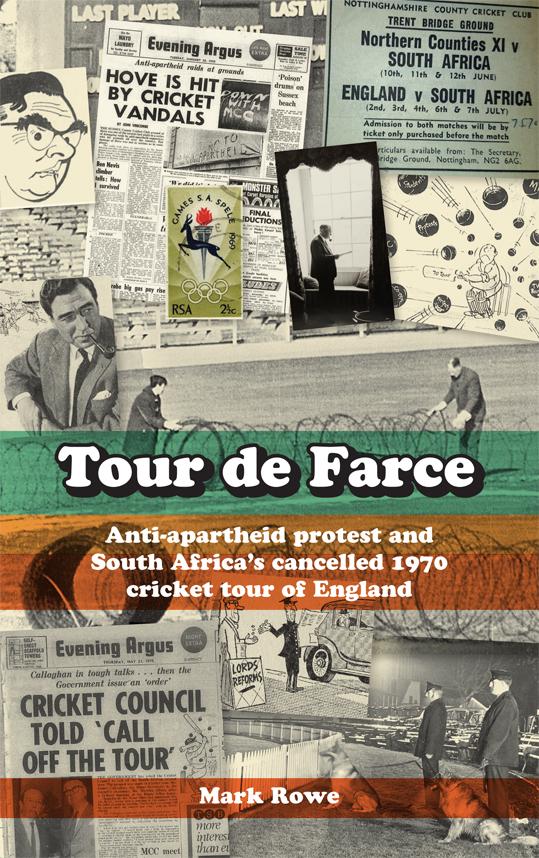

“Until the late 1960s all the campaigning was very polite,” said Mark Rowe, author of anti-apartheid history book Tour de Farce.

“But in the summer of 1969 Peter Hain became a prominent campaigner.

“Being a South African exile he picked up the idea of direct action rather than just being very reasonable and polite.

“They would do things like going to Springboks rugby matches and trying to get on to the pitch to stop the match.”

This new, more dramatic method of protest was popular among activists.

“Not only did the protesters enjoy it, but it was photogenic,” Mark.

“All of the newspapers reported on it, it captured a lot of attention.”

So the emboldened protesters took aim at cricket.

The Stop The Seventy Tour movement was formed to prevent the South African team playing in Britain.

The County Cricket Ground break-in came soon after.

But as much as the break-ins were received with surprise, there had been warnings.

“The Sussex club came across as totally bumbling,” Mark.

“The club had already found traces of weed killer on the outfield four days before.”

On the same day, the Marylebone Cricket Club passed a warning to Sussex after an anonymous letter was sent to Lord’s.

“Apparently the damage at Worcester was not enough,” it read.

“We have left a message in Sussex.”

The threat turned out to be false.

But the full force of that message was not felt until the morning after the break-in.

Though Sussex stood firm with Marylebone in supporting the South African tour, privately it raised concerns.

“Privately Sussex said to Lord’s they would rather not hold the match because they were worried about future attacks,” Mark said.

“The average Sussex committee member was an elderly white man with very conservative views.

“But the Hove ground was so easy to climb into that Sussex was open to more vandalism that could have ruined the pitch.”

The threat was not imagined.

Young Liberals chairman Louis Eaks told clubs they would have to expect “serious, irregular assaults”.

But after a month of posturing the English Cricket Council decided to cut half the tour schedule, including the Hove match.

Eventually the whole tour was called off.

Had it gone ahead in Hove, historian Mark thinks it would have been disastrous.

“It would have been a financial flop because hardly anyone would have braved the protesters,” he said. “Sussex may well have been among counties that would have gone bust.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here