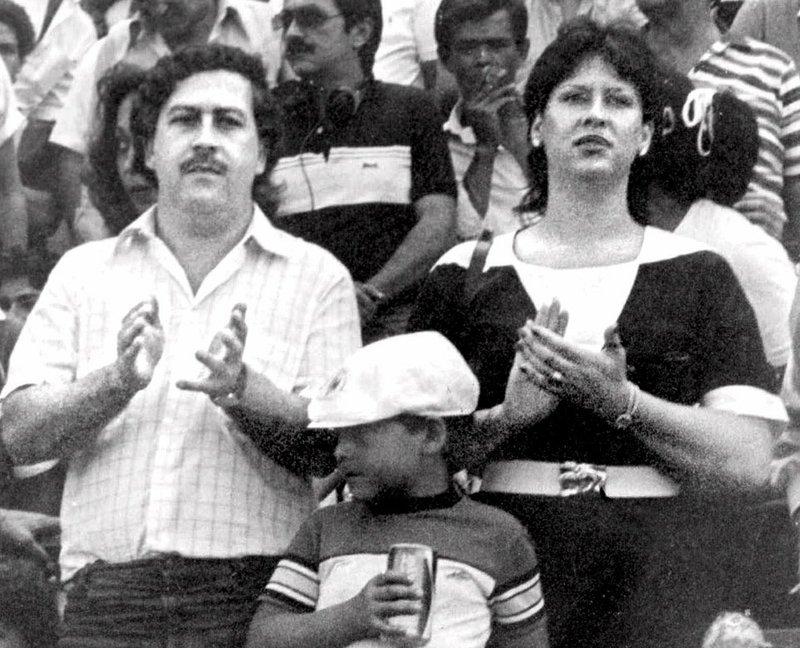

WHEN cocaine kingpin Pablo Escobar was shot dead in December 1993 the day after his 43rd birthday, four hippos he had taken to his private zoo were left behind in a pond on his ranch in Colombia.

Since then, their numbers have grown to an estimated 80 to 100 and the hippos have made their way into the country’s rivers.

Scientists and local people have viewed Escobar’s hippos as invasive pests that should not be running wild on the South American continent.

But a new study, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, reveals Escobar’s hippos could be the saviour of the species.

Through a worldwide analysis comparing the ecological traits of introduced herbivores such as Escobar’s hippos to those of the past, the international research team – including scientists from the University of Sussex – found that such introductions restore many important traits that have been lost for thousands of years.

While human impacts have caused the extinction of several large mammals over the last 100,000 years, humans have since introduced numerous species, inadvertently rewilding many parts of the world such as South America, where giant llamas once roamed.

Study co-author Dr John Rowan, of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in the US, said: “While we found that some introduced herbivores are perfect ecological matches for extinct ones, in others cases the introduced species represents a mix of traits seen in extinct species.

“For example, the feral hippos in South America are similar in diet and body size to extinct giant llamas, while a bizarre type of extinct mammal – a notoungulate – shares with hippos large size and semiaquatic habitats.

So, while hippos don’t perfectly replace any one extinct species, they restore parts of important ecologies across several species.”

The research team said that what most conservation biologists and ecologists think of as the modern “natural” world is very different than it was for the last 45 million years.

They explained that, even recently, rhino-sized wombat-relatives called diprotodons, tank-like armoured glyptodons and two-story tall sloths ruled the world.

The researchers said that the giant herbivores began their evolutionary rise not long after the demise of the dinosaurs, but were abruptly driven extinct beginning around 100,000 years ago, most likely due to hunting and other pressures from our Late Pleistocene ancestors.

The team found that by introducing species across the world, humans restored lost ecological traits to many ecosystems, making the world more similar to the pre-extinction Late Pleistocene and counteracting a legacy of extinctions.

Lead author Erick Lundgren, a PhD student at The University of Technology Sydney in Australia, said the possibility that introduced herbivores might restore lost ecological functions had been suggested but not “rigorously evaluated”.

To that end, the researchers compared key ecological traits of herbivore species from before the Late Pleistocene extinctions to the present day, such as body size, diet and habitat.

Mr Lundgren said: “This allowed us to compare species that are not necessarily closely related to each other, but are similar in terms of how they affect ecosystems.

“By doing this, we could quantify the extent to which introduced species make the world more similar or dissimilar to the pre-extinction past. Amazingly they make the world more similar.”

He said that was largely because 64 per cent of introduced herbivores are more similar to extinct species than to local native species.

The introduced “surrogates” for extinct species include evolutionary close species in some places, such as mustangs, wild horses in North America, where pre-domestic horses of the same species lived but were driven extinct.

Dr Rowan said: “Many people are concerned about feral horses and donkeys in the American south west, because they aren’t known from the continent in historic times.

“But this view overlooks the fact that horses had been present in North America for over 50 million years – all major milestones of their evolution, including their origin, takes place here.

“They only disappeared a few thousand years ago because of humans, meaning the North American ecosystems they have since been reintroduced to had coevolved with horses for millions of years.”

Study senior author Dr Arian Wallach, also of University of Technology Sydney, said: “We usually think of nature as defined by the short period of time for which we have recorded history, but this is already long after strong and pervasive human influences.

“Broadening our perspective to include the more evolutionarily relevant past lets us ask more nuanced questions about introduced species and how they affect the world.”

The research team concluded that when looking beyond the past few hundred years – to a time before widespread human caused pre-historic extinctions – introduced herbivores make the world more similar to the pre-extinction past, bringing with them broader biodiversity benefits.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here