WHATEVER ailment you might be suffering from, Nicholas Culpeper had a “cure” for it.

Searing hangover after a night out? Try snorting the juice of ivy berries.

Cursed with a bout of flatulence? Nibble on some rosemary.

Coughing? Chew some tobacco.

These treatments might sound primitive, but in the 17th century Nicholas believed they were the future.

Medicine was crude, risky and inaccessible when the botanist was born in 1616 in the village of Ockley near the Surrey/Sussex border.

Most doctors were still using Roman medical texts written in Latin and published centuries before.

Practices like bloodletting and toxic medicines were common and unlikely to change with the Royal College of Physicians’ stranglehold on the field.

“At this time medicine was only practised by elite physicians,” said Sussex Wildlife Trust senior learning officer Michael Blencowe.

“They would charge exorbitant prices for their secret remedies and would not even demean themselves to talk to patients.”

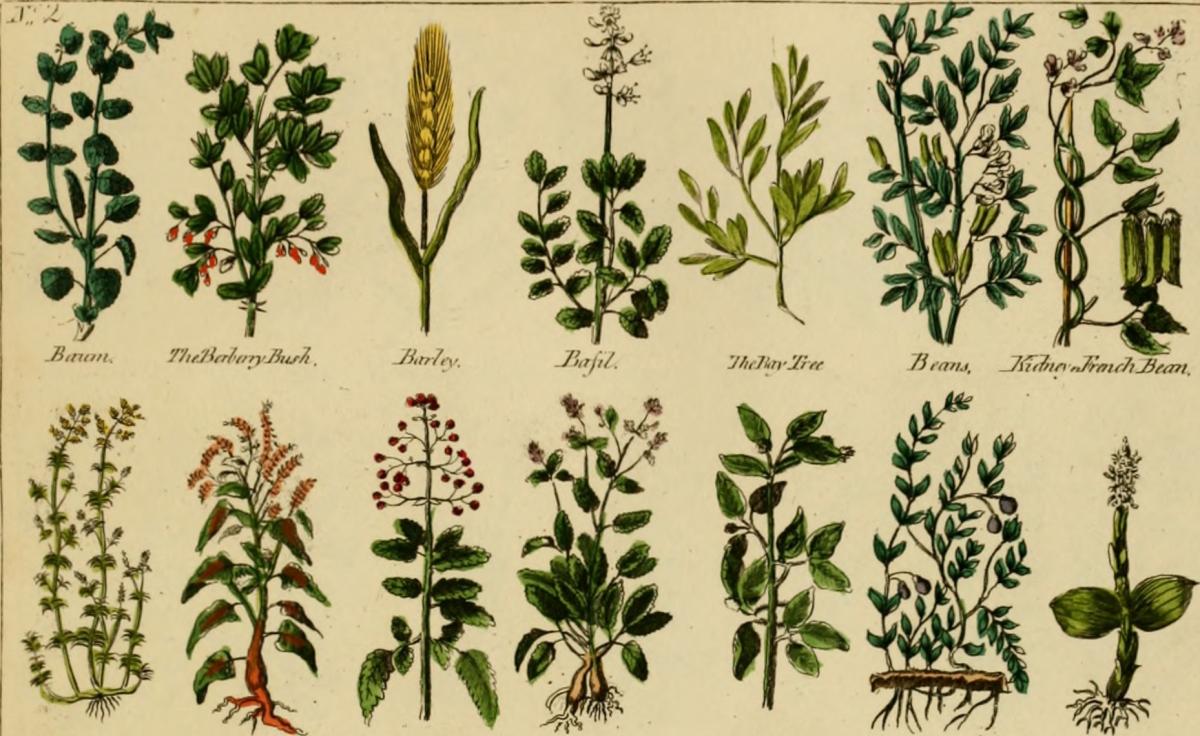

But Nicholas had a different outlook on medicine thanks to his upbringing in Isfield, near Lewes. His maternal grandmother had taught him about the medicinal powers of plants and herbs.

Young Nicholas often leafed through his grandfather’s collection of books, learning about astronomy, astrology and medicine.

He also learnt about love.

“In 1634 Culpeper and his Sussex sweetheart planned a secret Lewes wedding and a speedy elopement to the Netherlands,” said Michael.

“But tragedy struck when his love-struck lady’s carriage was struck by a lightning bolt as she travelled over the Downs near Lewes.

“She died instantly.”

Heartbroken, Nicholas moved to London and became an apothecary assistant, cataloguing medicinal herbs.

It was during his six years here that the botanist became angry about the state of medicine.

He lamented the high prices doctors charged for their cures.

He hated the way they wrote in Latin, preventing the common people from curing themselves.

And Nicholas especially hated the way they neglected to examine their patients, only observing their urine.

In his own words “as much p*** as the Thames might hold” was no use in finding out what plagued the sick.

So in 1640 he married the 15-year-old heiress of a merchant and used his newfound wealth to set up a pharmacy in the poorer East End.

In a typical morning the botanist would see 40 patients, providing them with cures free of charge.

His work in London made waves not just in the medical sphere, but in the political sphere too.

By the beginnings of the English Civil War in 1642 Nicholas was known as both a rebel doctor and a die-hard republican, his views of medicine and society bleeding into each other.

“No man deserves to starve to pay an insulting, insolent physician,” he said. “Three kinds of people mainly disease the people: priests, physicians and lawyers.

“Priests disease matters belonging to their souls, physicians disease matters belonging to their bodies, and lawyers disease matters belonging to their estate.”

An attempt by the Society of Apothecaries to try Nicholas for witchcraft angered him enough that he joined an anti-royal militia as a battlefield surgeon. But a shot in the chest in 1643 sent him back to the medical realm.

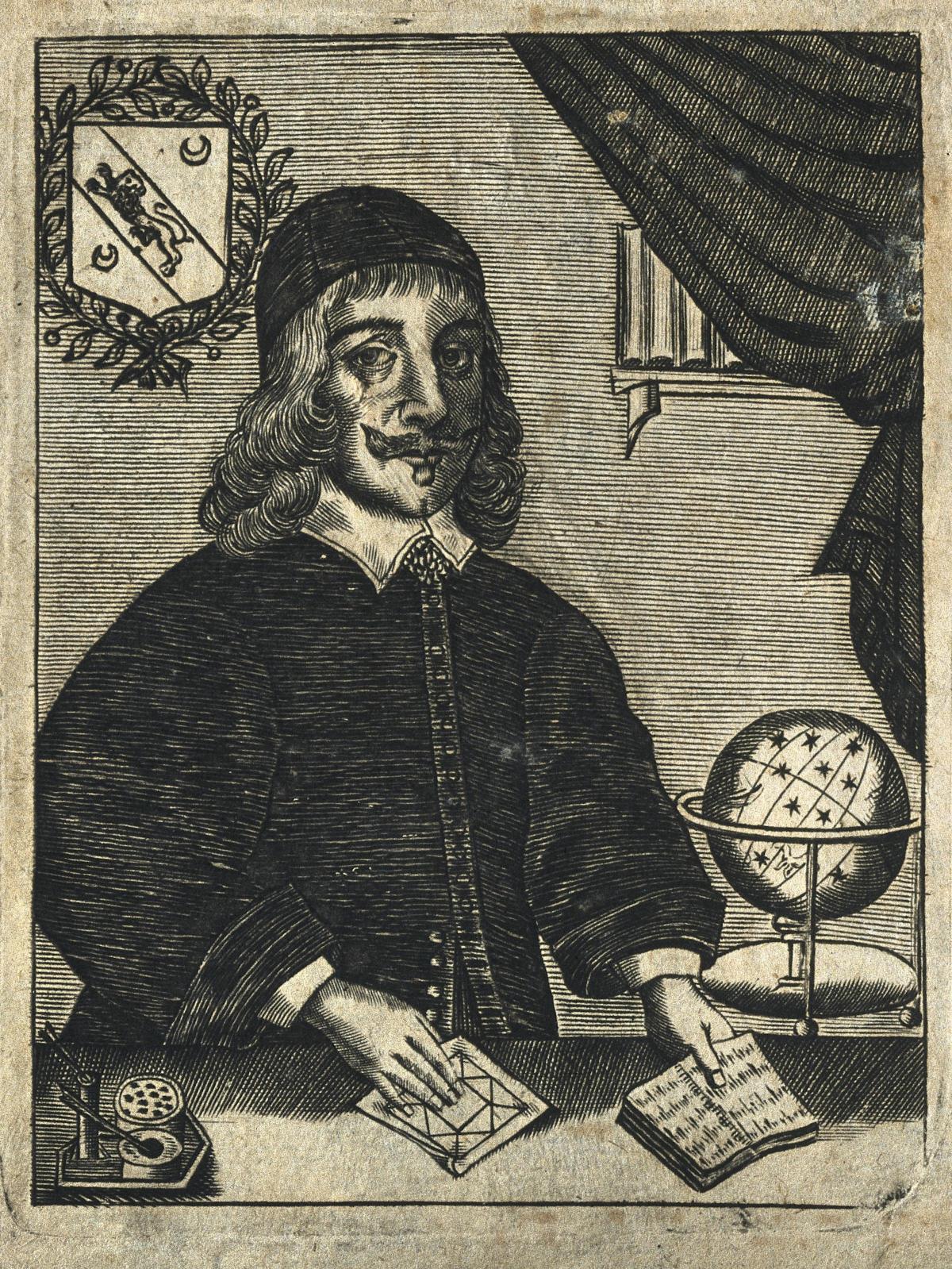

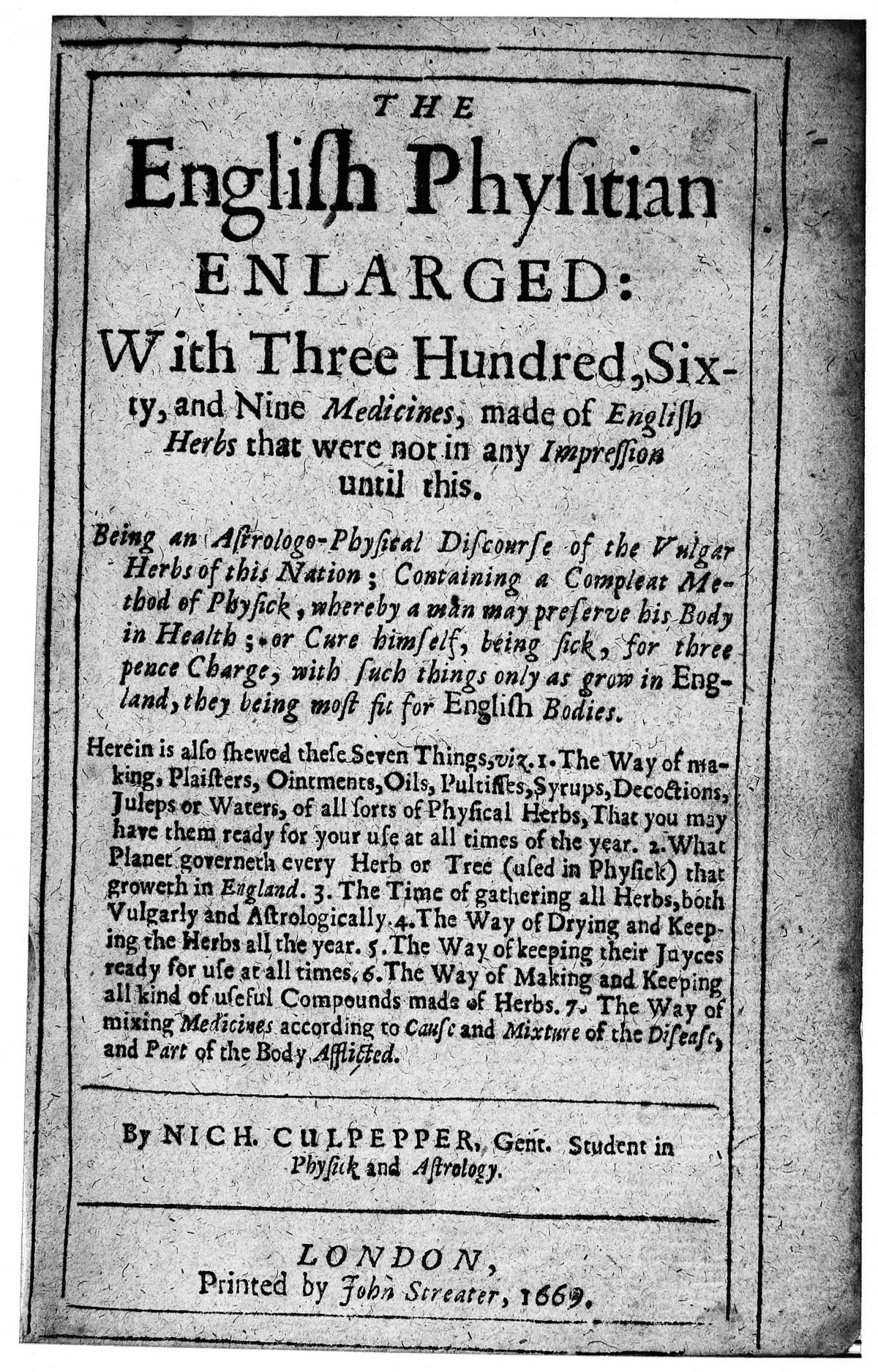

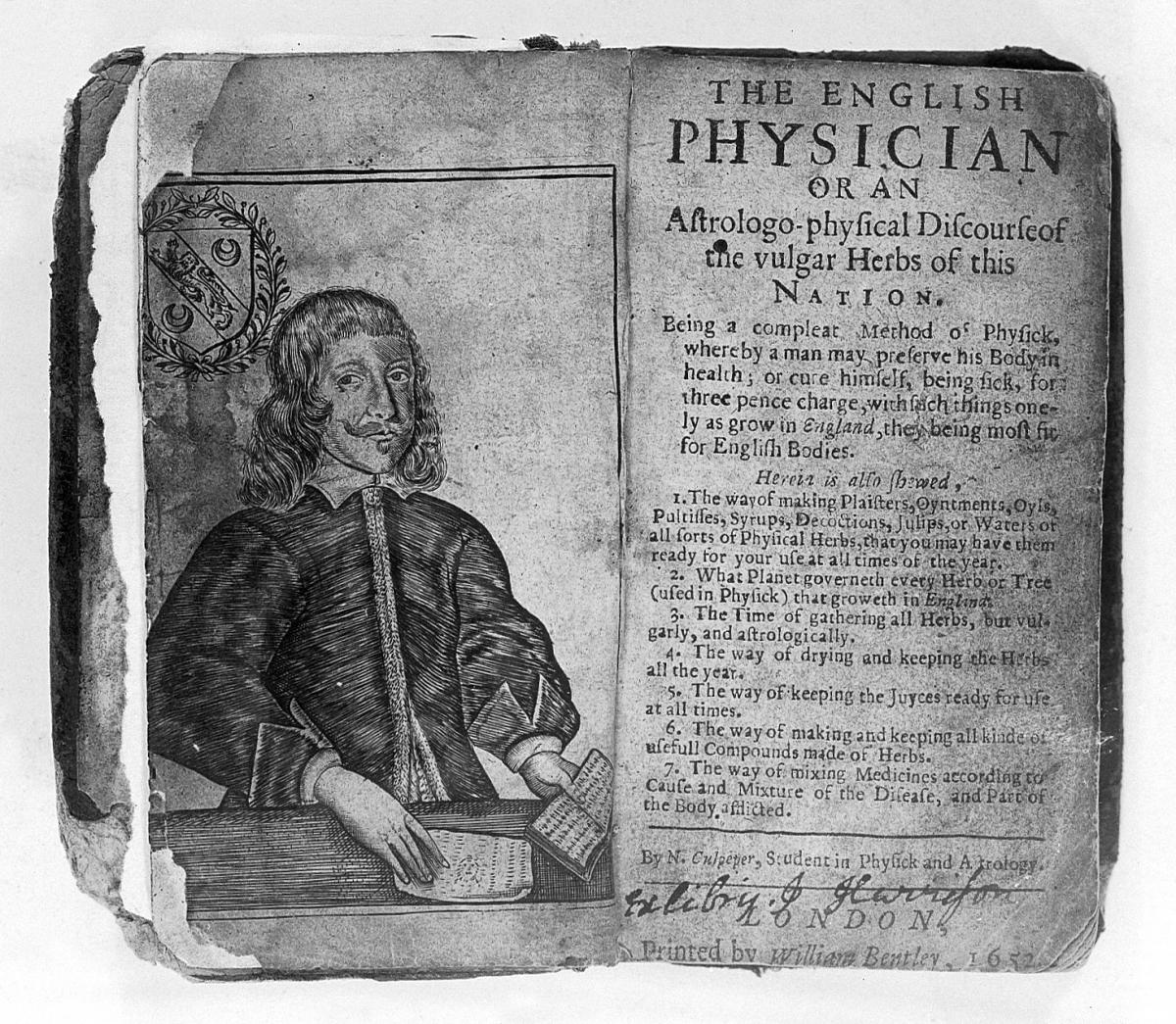

Translating Latin texts into English in his own act of rebellion, the rebel eventually dropped his 1652 botanical bombshell The English Physitian.

It was a book of his “choicest secrets, which I have had many years locked up in my own breast”.

Nicholas sold his book cheaply, aiming to spread his easy cures to as many as possible.

It remains in print today, one of the longest continuous print runs of any English book. It also ensures his legacy lives on well past his death in 1654.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here