UPON his death in 1916, Charles Dawson was hailed as a groundbreaking archaeologist.

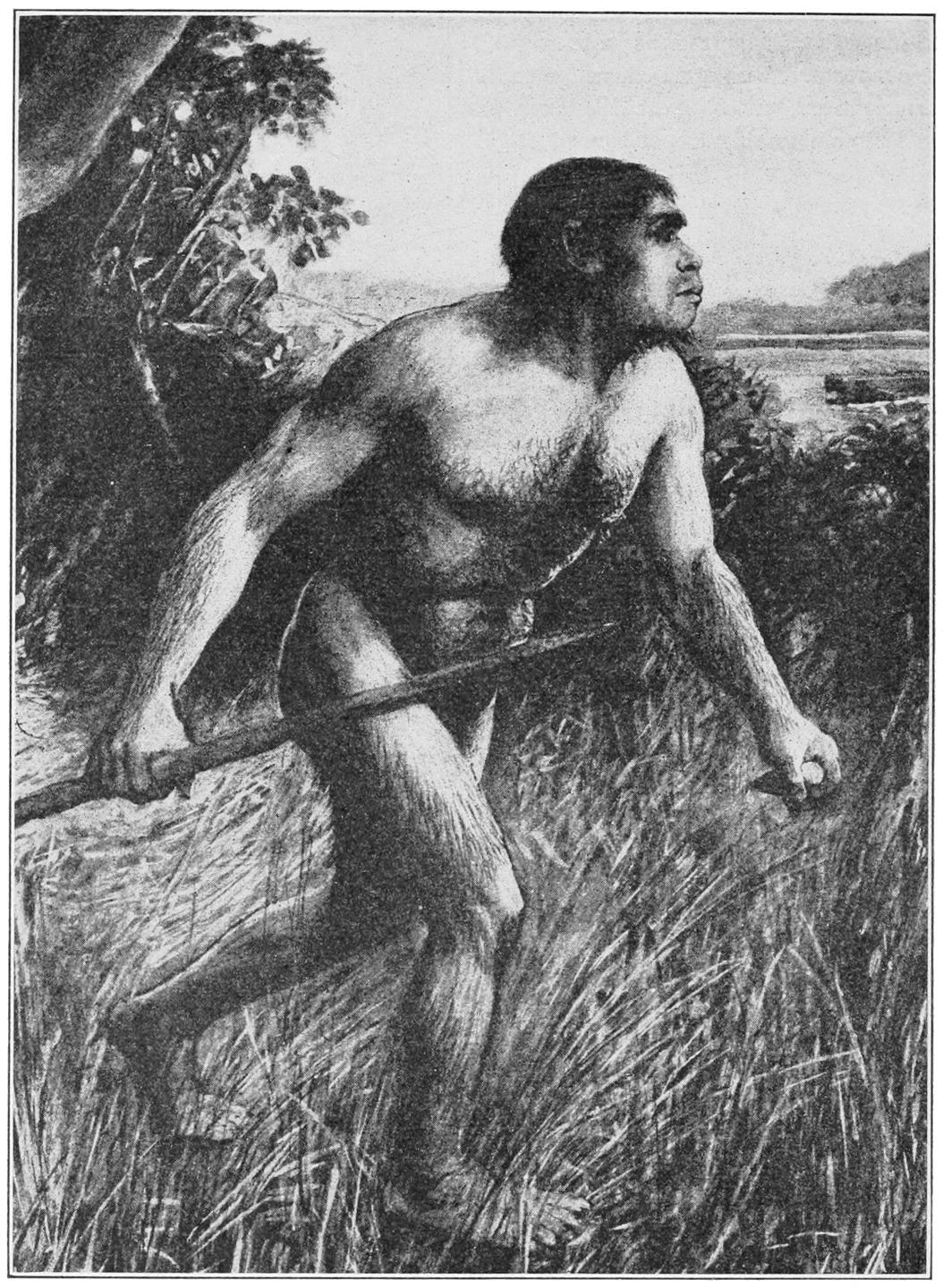

His reputation had shot into the stratosphere four years before when he claimed to have discovered the skull and jaw of the missing link between ape and man near the village of Piltdown, near Uckfield.

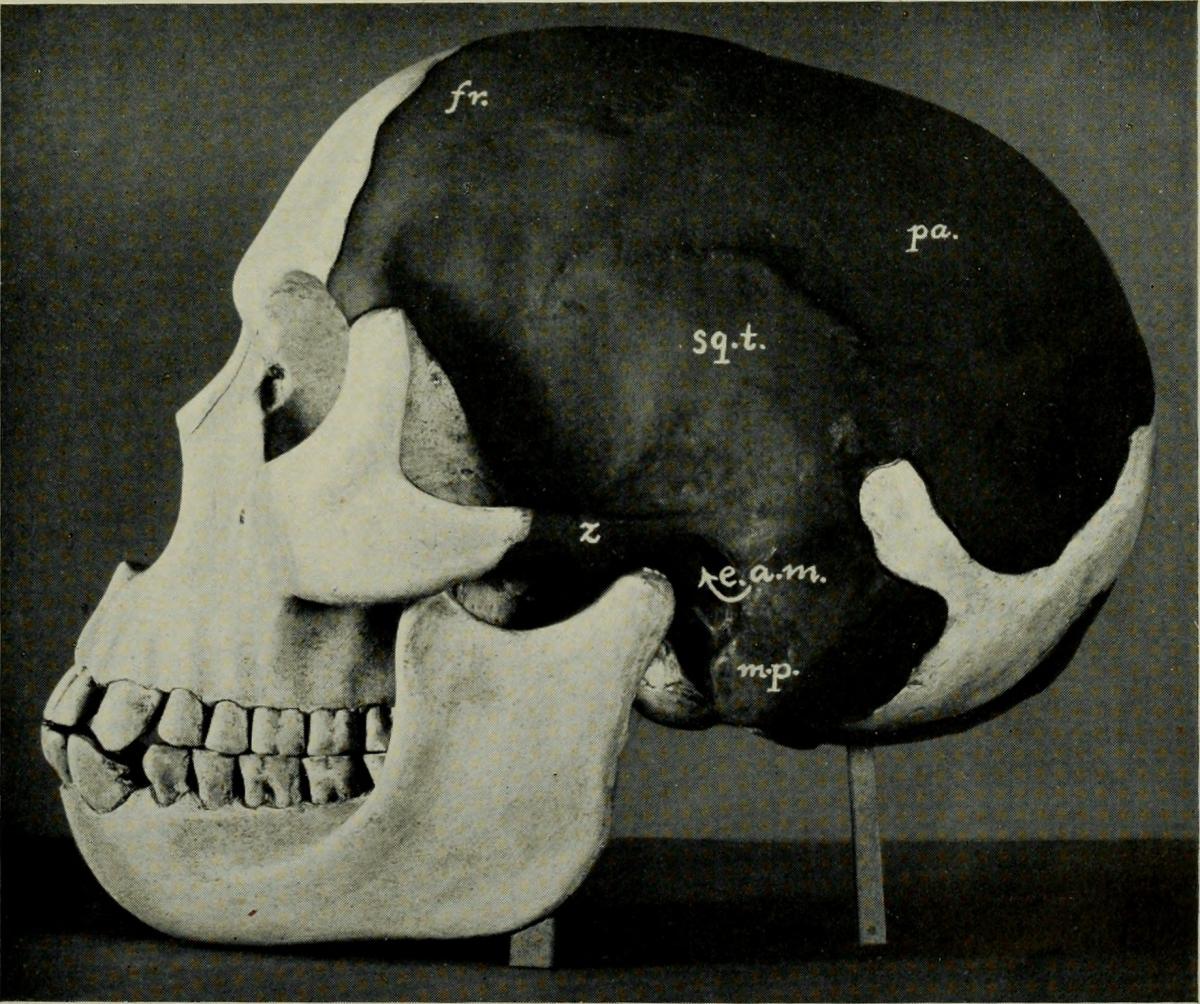

Its small brain size and chimpanzee-like teeth appeared to perfectly bridge the evolutionary gap. Three years later Charles found similar skull fragments in Sheffield Park.

By the time he died at 52, he had a collection of rare discoveries including a fossilised toad and a sea serpent he found in the Channel.

In fact, most of his finds were made within 12 miles of his Lewes home.

If that seems convenient, you would be right. In reality, Charles was arguably history’s most prolific fossil fraudster.

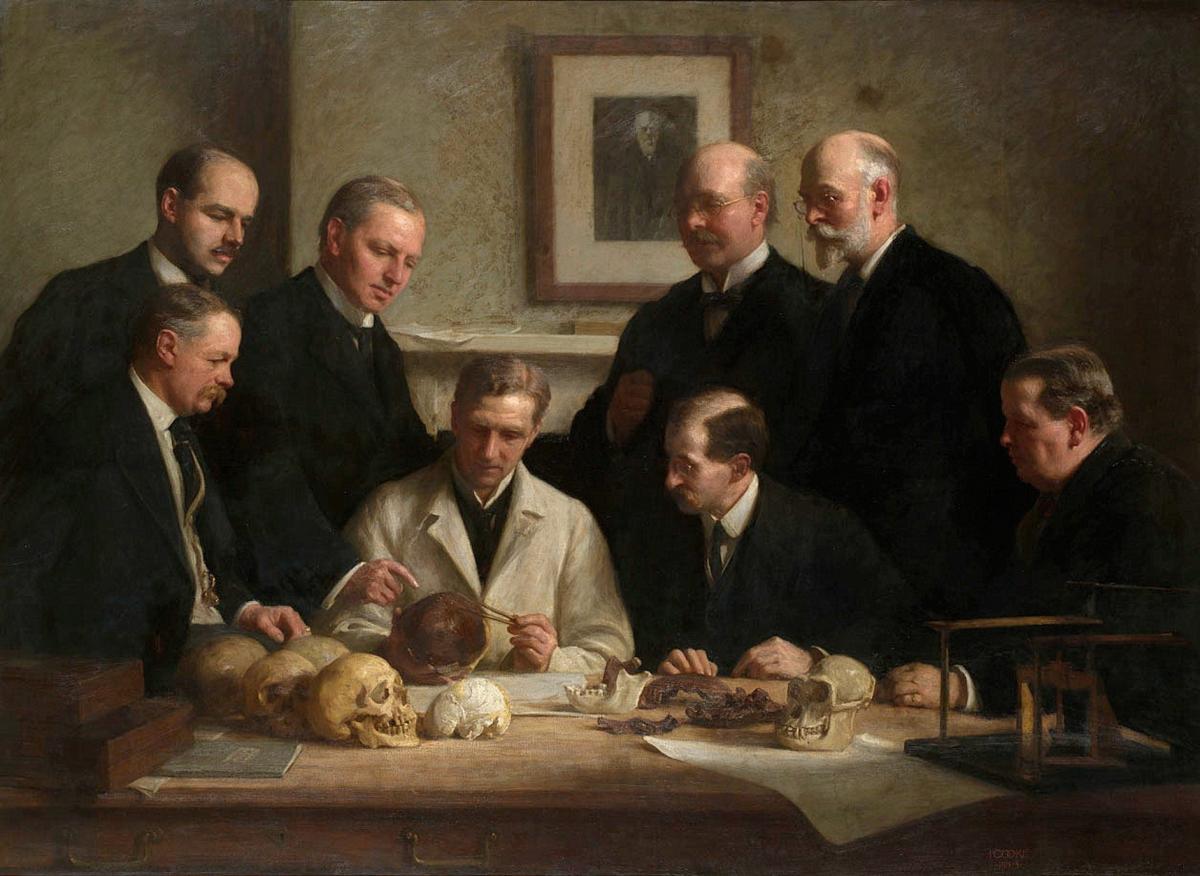

The thread began to unravel in 1953 when three scientists proved the “Piltdown Man” was actually a medieval human skull attached to a 500-year-old orangutan jaw with some chimp teeth thrown in.

Since then archaeologist Professor Miles Russell has exposed dozens of Charles’s other discoveries as fakes. So how did he get away with it for so long?

“People wanted the Piltdown Man to be true,” said Miles.

“It put British archaeology at the forefront of discovery. It was the missing link coming from the Home Counties.

“Fossils had been found in France and Germany, so people invested a lot into it.”

To archaeologists today, the forgery is obvious. The teeth had been worn down with a metal file.

But those who criticised Charles would end up looking foolish.

“Every time there seemed to be an issue, a solution would pop up,” said Miles.

“Some scientists thought the jaw and the skull couldn’t be connected, then a bone connecting them turned up.”

When the skull was reconstructed, its canine teeth were missing. Conveniently, a canine fitting the jaw was then found.

To many, Charles’s motivations are clear: the pursuit of fame.

But he had a lot to lose. Far from a down-and-out looking to lie his way up the ladder, Charles was a respected solicitor.

“If he was caught out he would have been disgraced,” said Miles.

“But it became an addiction.

“You often see it with career criminals who get more extravagant. A lot of these forgeries are brazenly ridiculous.

“These days fossil forgeries are usually done to make money by selling them, but Dawson pretty much bankrupted himself.”

Scientific consensus is that Charles was behind the Piltdown hoax.

But some tout the involvement of a Frenchman called Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, a philosopher who helped uncover the missing canine before disappearing to France a few days later.

A few even claim Sherlock Holmes author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle played a role, having been a friend of Charles.

But Miles’s theory has the most political intrigue. He believes some of the Piltdown “finds” were planted by rivals of Charles seeking to expose him.

This included a cricket bat carved from a mammoth tusk, an artefact so obviously fake it would knock Charles off his perch. Instead the set-up shot him to superstardom.

“He had fallen out with the Sussex Archaeological Society,” said Miles.

“It’s quite obvious somebody had planted the cricket bat.

“But the Piltdown Man was referred to as the first Englishman so people thought it made sense for him to be buried with a cricket bat.

“The area that was being dug wasn’t protected. The soil was dug out into piles and were sifted through, so someone could have planted finds in there, but someone had actually planted the cricket bat into the ground to dig up.”

Dying at 52 meant Charles was never disgraced in his lifetime.

“But it would have been interesting to see what he planned to try next.

As Miles said: “You’d think finding the missing link would have been enough.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel