RIOTING and mass working-class protest was more associated with northern industrial towns than sleepy seaside resorts in Victorian times.

But in 1885 a summer of sedition took over Worthing, led by the feared Skeleton Army.

Teenage boys and young men wearing caps with yellow ribbons, some with sunflowers in their

button-holes, rioted for three days in August, even attacking the town hall.

But what prompted their actions? Not a demand for better pay or voting rights, but simply the right to drink.

Their fears began in autumn 1883 when the Salvation Army came to Worthing for the first time.

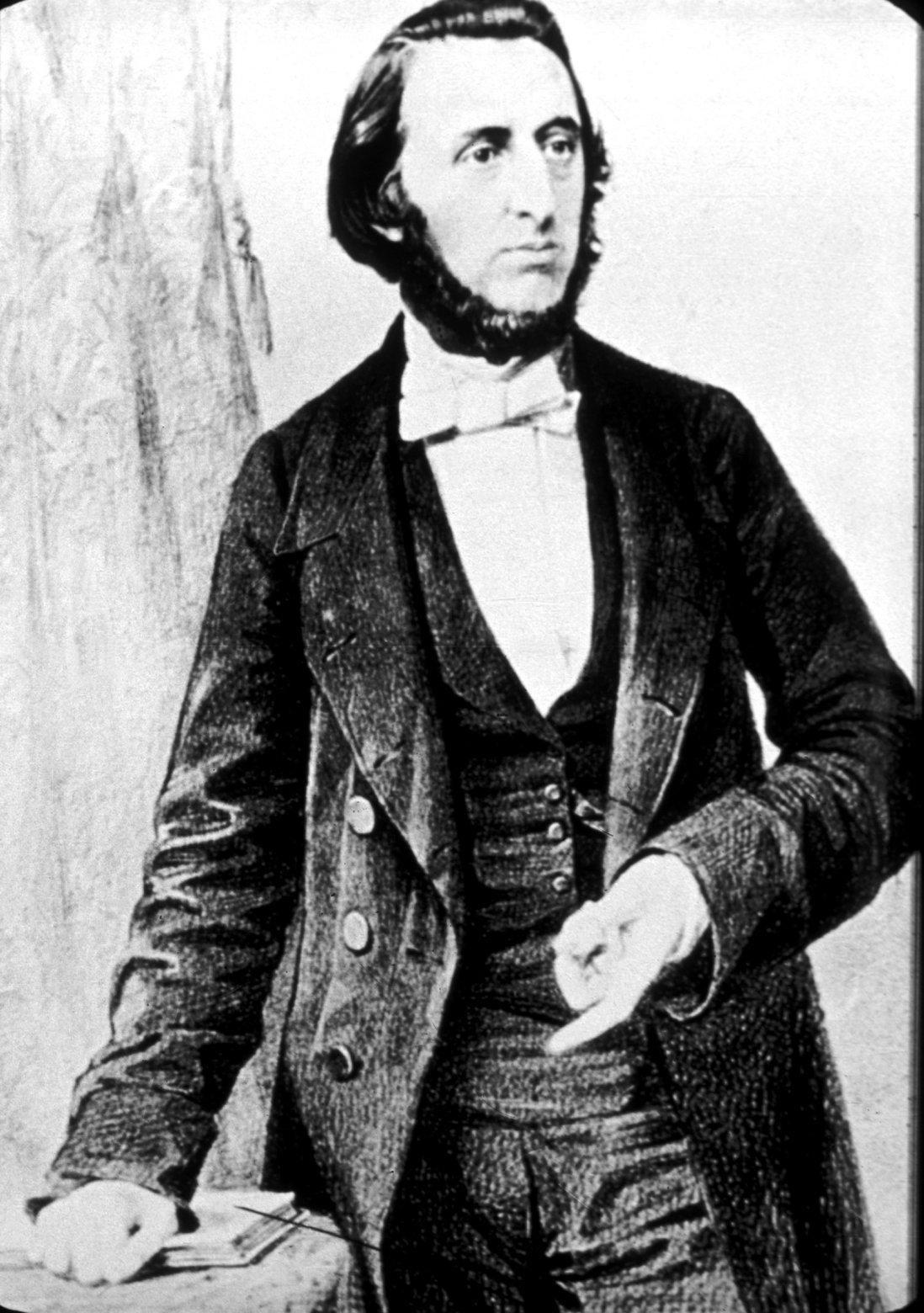

Founded five years before by Methodist preacher William Booth, it campaigned vigorously against the evils of alcohol, tobacco, gambling, and other pastimes enjoyed by the Victorian working classes.

This made a lot of people in Worthing very nervous, not least the shopkeepers and hoteliers who feared their trade would be damaged by the army’s demands and the bad publicity it would bring.

Things were relatively quiet at first.

The alley leading to the army’s meeting hall was tarred repeatedly, prompting its soldiers to exercise restraint in fear of sparking a riot.

But that approach went out of the window in April the next year when 23-year-old firebrand Ada Smith was appointed captain of the Worthing branch.

She took aim at the town’s “vilest spots” of decadence, holding rowdy street parades twice each week.

This did not go down well.

Working-class men enraged at the army’s demands pelted marchers with eggs filled with blue paint. Two even went to jail for it.

And the middle class, fearing visitors would be driven away from Worthing, scribbled furious letters to the local papers.

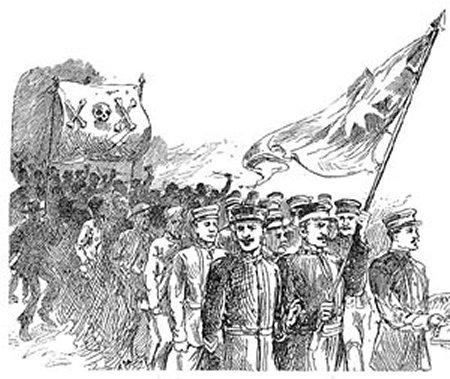

Thus the Skeleton Army was formed to drive the Salvation Army out of the town.

Hoisting banners emblazoned with skeletons, they marched through the streets in uniform in a show of force against the Salvationists.

“Banners were carried in the procession, at the head of which were two young men carrying sticks, on each of which was a doll, supposed to represent a skeleton,” the Sussex Coast Mercury reported in June.

Tensions were rising. The army’s founder Mr Booth wrote to the Home Office complaining Worthing’s magistrates were refusing to try the “riff-raff molesting the Salvation Army”.

In some cases that was certainly true, in large part because the magistrates supported the Skeletons.

“Certainly the attitude of one magistrate, Mr F W Tribe, shows marked hostility against the Salvation Army,” folklorist Chris Hare wrote in the Folklore journal.

“In July, when one Salvationist applied to the bench for a summons against those who had assaulted him, Tribe told him: ‘You know what you do provokes others to interfere with you, and then you come to us for protection.’”

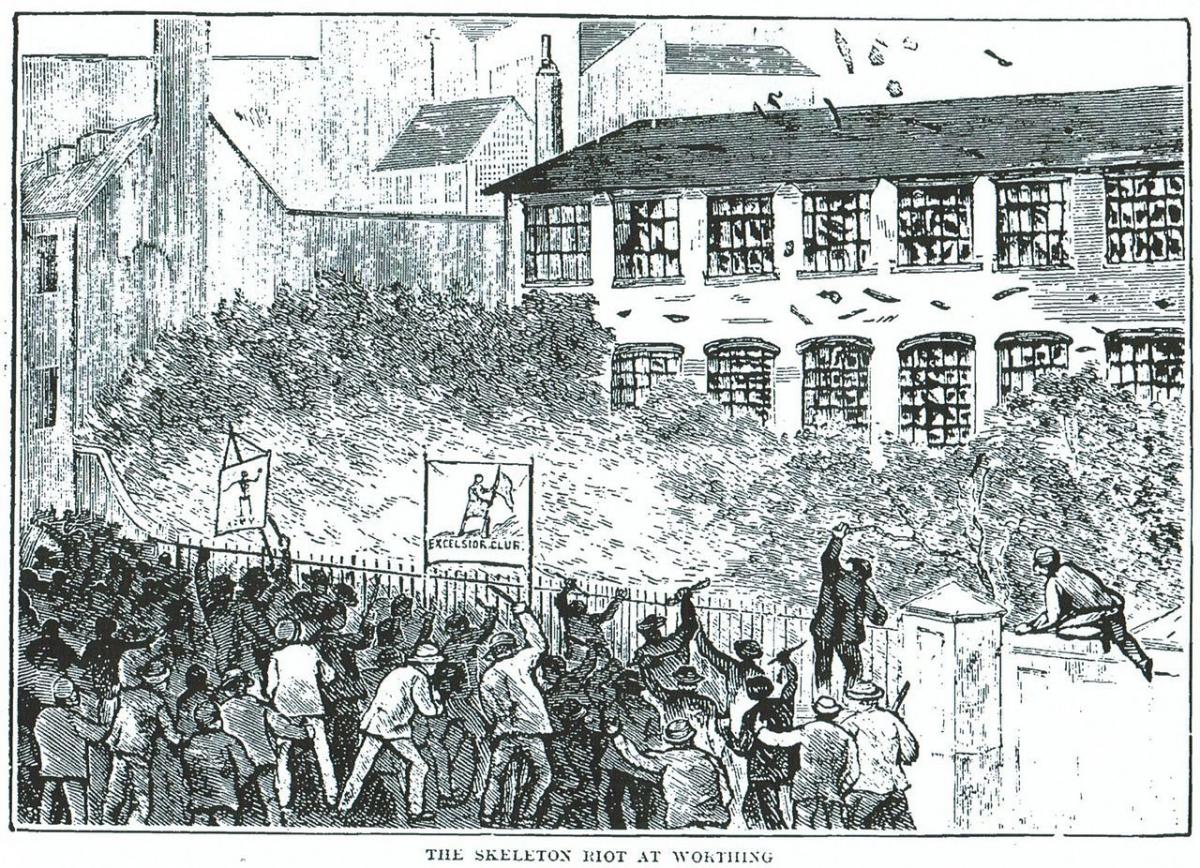

Then on August 18 the flashpoint came.

Emboldened by the town’s uncritical support, the Skeletons began attacking Salvationists and the police defending them. The rioting continued for two more days until chief magistrate Colonel Wisden decided he had had enough.

Taking to the steps of the town hall, he read the Riot Act, giving the Skeletons an hour to disperse.

As expected, this was not a popular move.

“The concluding portion of the colonel’s speech was met with howls of derision which terminated in the people singing Rule Britannia with special emphasis on the chorus, ‘Britons never, never will be slaves.’,” one account claimed.

“’I don’t want you to be slaves,’ shouted the colonel. “’Then speak as a gentleman ought to speak, and apologise,’ roared a man in the crowd.

“’Now will you go home quietly?’ asked the colonel, and from a hundred throats the response was an emphatic ‘No!’”

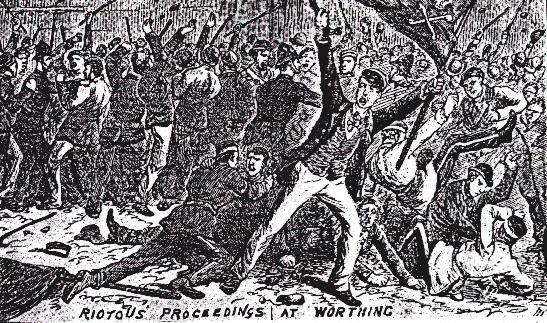

So the Dragoons were called in from Brighton to clear the Skeletons off. The crackdown was somewhat ugly. One protester died of a whack from a policeman’s truncheon.

By this time, some middle-class supporters were becoming weary of the army they helped foster. Their main concern, that rowdy Salvation Army protesters would drive visitors away, had not really been solved by the Skeletons. If anything they had made it worse.

“We have been accustomed to regard the London rough as the most completely developed species of rascality, but he could certainly find his match in Worthing,” the Daily Chronicle had written.

But those who created the Skeleton Army were not ready to stop just yet. Becoming less focused on the Salvationists, they were ready to take their anger out on anything that annoyed them.

In October a 500-strong mob marched to Shoreham, smashed the windows of toll booths on the Norfolk Bridge and pelted the town’s police station with stones.

Days later a hated landlord was confronted by a group of Skeletons who burned an effigy of him metres from his front door.

Ringleaders were rounded up after their protests but proved too numerous to tackle when they were in action.

So many in Worthing feared a riot on Bonfire Night because members of the Skeletons were also members of the Bonfire Club.

Their worries were not ill-founded.

“After a preliminary exhibition of fireworks, tar barrels were obtained and rolled through the streets,” the Worthing Gazette reported.

“The police at first attempted to stop the blazing tubs, but their action was resented, stones were freely thrown and a local member of the force was badly cut on the face.

“No further resistance was offered by the police, and two old boats were afterwards set on fire and drawn through the streets.”

That was the Skeleton Army’s big finale. Afterwards ringleaders were easily picked off and special constables were recruited to keep the peace.

After a summer of tossing and turning, Worthing was back to its sleepy self.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel