IF YOU took a stroll along the seaside in 1895, you would likely notice quite a few differences.

The sight of three African kings walking down Brighton promenade would be one of them.

Of course, the city has always been a haunt for royalty since Prince George arrived in the 18th century.

But this was no leisure trip, even if the kings were sampling the sights. This was business.

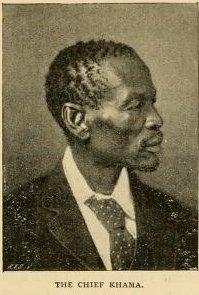

Khama III, Bathoen I, and Sebele I were tribal kings from Botswana, then known as the Bechuanaland Protectorate.

Enjoying some independence but still ultimately ruled by the British Colonial Office, King Khama was its leader in 1895.

But the limited freedoms Bechuanaland had were under threat from colonialist Cecil Rhodes, the prime minister of the Cape Colony, now South Africa.

“Cecil Rhodes wanted to build a railway from Cape Town to Cairo and essentially annex Botswana,” said Bert Williams of Brighton and Hove Black History.

“He would have controlled 50 miles either side of the railway and built towns along it. The kings would have been reduced to nothing.”

Alarmed, Khama and neighbouring tribal kings Bathoen and Sabele decided they would go straight to Queen Victoria to convince her not to listen to Mr Rhodes.

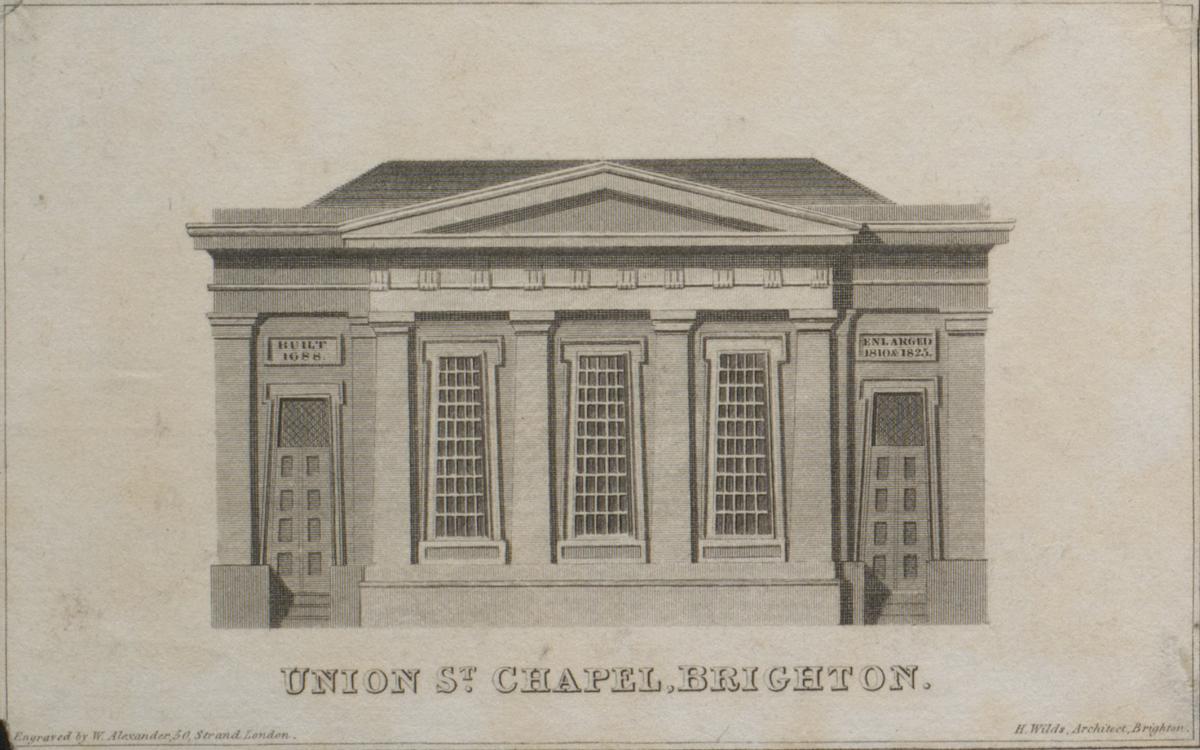

So they enlisted missionary the Reverend William Willoughby, a former preacher at Brighton’s Union Street Church, and set sail.

“At the time England was going through an evangelical phase, so it was the right time for Khama to visit, he got a lot of sympathy,” said Suchi Chatterjee of Brighton and Hove Black History.

“They weren’t asking for freedom, they were asking to stay the way they were. Khama was very shrewd.”

On September 14 the three kings arrived in Brighton by rail. All devout Christians, they were to stay with Union Street Church secretary George Singleton at his Ditchling Road house.

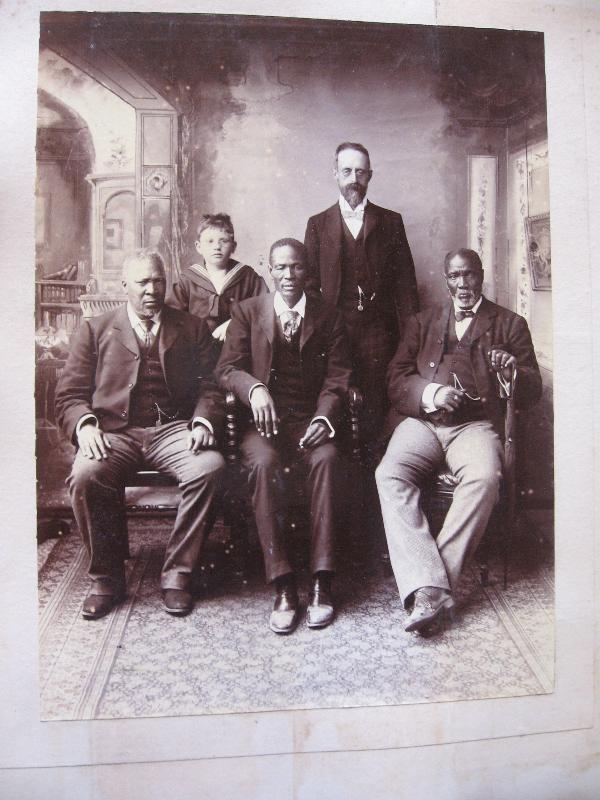

The Rev Willoughby’s eight-year-old son Howard, fluent in Setswana, stayed with them. The kings actually favoured the boy as their interpreter rather than his father, as he was a more honest translator.

That same day they visited Brighton Aquarium and caught a concert at Brighton Pavilion. The next day they took part in Sunday services at Union Street Church, now The Font pub.

But the kings were seated on the back pew.

The Brighton Herald reported “a large number of the congregation availed themselves of the opportunity of shaking the chiefs by hand”.

“Newspapers often described them as chiefs rather than kings, an indicator of colonial racism at the time,” said historian Ms Chatterjee.

In the evening, pastor Reverend R J Campbell asked his congregation to rise if they sympathised with King Khama. All of them did.

So the kings left with a good impression of Brighton.

“I and my brother chiefs all agree we like Brighton far better than London,” King Khama was reported as saying.

“There is beauty there and air and sunshine and sea. We were met with kindness in London, but the friendliness of the people in Brighton made us feel really at home.”

In fact, they loved it so much they returned again later on September 24 after a tour of England.

That day they visited the recently-built Elm Grove School.

“They enjoyed watching the students Maypole dancing,” said historian Mr Williams.

“They had their picture taken there, but we haven’t been able to track it down yet,” Ms Chatterjee said.

Later they toured a dairy factory in Glynde and the villages of Steyning and Bramber.

But October 2 was the main event: the Congregational Union convention of priests at the Brighton Dome.

After speeches by the kings, the smitten pastors passed a resolution calling on the Government to “find it possible in some way” to keep Bechuanaland as a British protectorate.

By the time Khama met Queen Victoria in November and exchanged gifts, public opinion was on his side. Bechuanaland would remain separate from the Cape Colony. Mr Rhodes’s plans were thwarted.

Seventy years later, Khama’s grandson Sir Seretse Khama became the first president of a newly independent Botswana.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article