THE brutal fighting of the First World War never reached Britain’s shores.

But its impact on Brighton and Hove, as with everywhere else in the country, was keenly felt.

Historian Kevin Newman’s new book A-Z Of Brighton And Hove is packed with information on how the Great War shaped our city.

Its most obvious impact was the conversion of Brighton into a military hospital town where even the Royal Pavilion became a makeshift hospital for brave Indian soldiers.

Some of the consequences were more subtle. At the war’s outbreak in 1914, German Place in Kemp Town was renamed Madeira Place.

But the war’s greatest impact in the town was human, both its devastating death toll and its elevation of soldiers to heroes.

Edward Thomas from Brighton is believed to have fired the first British shot of the war at 7am on August 22, 1914.

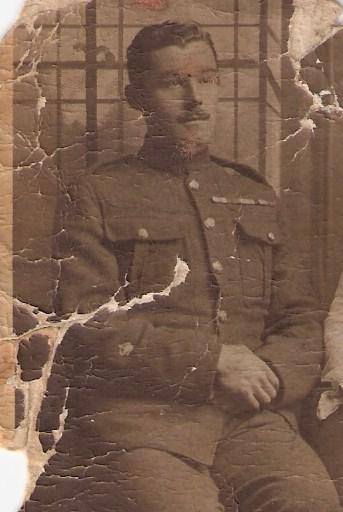

He survived the conflict and moved to Southdown Avenue in 1923 after he was discharged from Preston Barracks. Edward was best known as a moustachioed, medal-adorned doorman at the Duke of York’s cinema.

As much as Brighton “started” the war, Hove is said to have “ended” it.

“The man who sent the telegram to end the conflict was from Hove,” wrote historian Kevin.

But tucked away in Hove Cemetery is the remarkable story of one soldier who showed extreme courage. Bernard Norris Butcher is buried in the graveyard, having died of an unknown illness in 1921 at the age of 32.

His simple white grave gives little indication of the wartime heroics which earned him a Distinguished Conduct Medal, the second-highest honour for a British soldier.

In January 1915, Bernard was one of the thousands of British soldiers holed up in freezing waterlogged trenches near the French village of Cuinchy.

Soldier-poet Robert Graves wrote about the horrific living conditions.

“Cuinchy bred rats. They came up from the canal, fed on the plentiful corpses and multiplied exceedingly,” he wrote.

“While I stayed here with the Welsh, a new officer joined the company.

“When he turned in that night, he heard a scuffling, shone his torch on the bed and found two rats on his blanket tussling for the possession of a severed hand.”

On January 29 the Germans launched a punishing advance, leaving “Solid Sussex” Bernard and his Royal Sussex Regiment comrades surrounded in mini-strongholds known as the Brickstacks.

“The casualty rate for officers was very high,” wrote historian Kevin, with research from Amanda Jane Scales.

“On the morning of the 29th the last officer had been shot through the head, leaving Bernard, acting company sergeant-major, as the highest-ranking soldier.”

German soldiers used ladders and axes to attempt to climb into the Brickworks, nicknamed “the Keep” by British soldiers.

But as one contemporary report shows, Bernard was determined not to let that happen.

“Solid Sussex inside the Keep [ensured the German] ladders and stormers were hurled to the ground, whilst bombs were thrown on the heads of the attackers,” the report read.

Another wrote: “During an attack on the Keep, he, while under heavy machine-gun fire, bombed the enemy and was largely instrumental in defeating the attack.”

The next year Bernard was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal “for conspicuous gallantry at Cuinchy”.

“He has on many occasions throughout the campaign rendered valuable service and has invariably shown great courage, resource and devotion to duty,” the citation read.

Later in that year he was awarded the Military Cross for more of his “invaluable energy and cheery pluck” in the face of adversity.

Bernard survived the war and managed the Battle of Trafalgar pub in his home town of Portslade. In 1921 he died after he was taken ill in the Caribbean.

But perhaps the biggest tragedy is Bernard did not get the wartime recognition he deserved, says historian Kevin.

“The Distinguished Conduct Medal is often considered a near miss for a Victoria Cross, and has to be, in most cases, recommended by an officer and three witnesses,” Kevin wrote in A-Z of Brighton and Hove.

“As you will recall there were no officers left to recommend Bernard. Had there been so, then surely Portslade would have its own holder of the Victoria Cross.”

A-Z of Brighton and Hove by Kevin Newman is available to buy at amberley-books.com.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel