“WHAT would have become of my children if I had been put into some poorhouse?” the letter stuck up in the Onslow Arms asked.

“Now if I go out at the door I do see great comfort.”

The letter in the Loxwood pub was posted up in January 1837 at the request of its author, Ann Mann.

The dream land she was speaking of was the British colony of Upper Canada, now known as Ontario province. Ann, her husband Samuel and their four youngest sons had swapped the village of Wisborough Green for a new life in the colony the year before.

But they were far from the only ones to make the journey. Between 1832 and 1837, the Petworth Emigration Committee sent 1,800 working-class people across the pond, backed by wealthy landowners and church figures.

The scheme was seen as a solution to growing poverty and simmering class tensions in rural Sussex.

The dawn of efficient farming machinery had stripped many labourers of their jobs and pushed down conditions and pay for others.

Many faced the humiliation of the workhouse, where families were split up and told to toil in horrendous conditions.

In 1830 this growing resentment had exploded in the destructive Swing Riots across the South. Struggling farm workers resorted to wrecking the very machinery which caused their poverty.

In Horsham 1,000 labourers were jailed after they demanded magistrates sign off on a pay increase.

Two years later, whether out of sympathy for those in poverty or fear of more rebellion, landowners and charities formed the Petworth Emigration Committee.

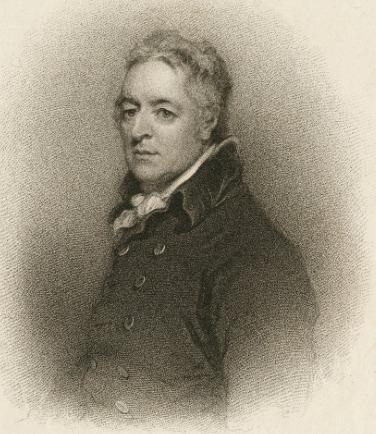

The group was headed by the town’s rector, the Reverend Thomas Sockett.

From a humble background, the churchman was good friends with George Wyndham, the Earl of Egremont, who owned vast estates in Sussex and lived in Petworth House.

All parties believed helping the poor to start new lives in Upper Canada would improve conditions in Sussex.

The Earl agreed to pay the £10 fee for any labourers on his land who wanted to make the long trip.

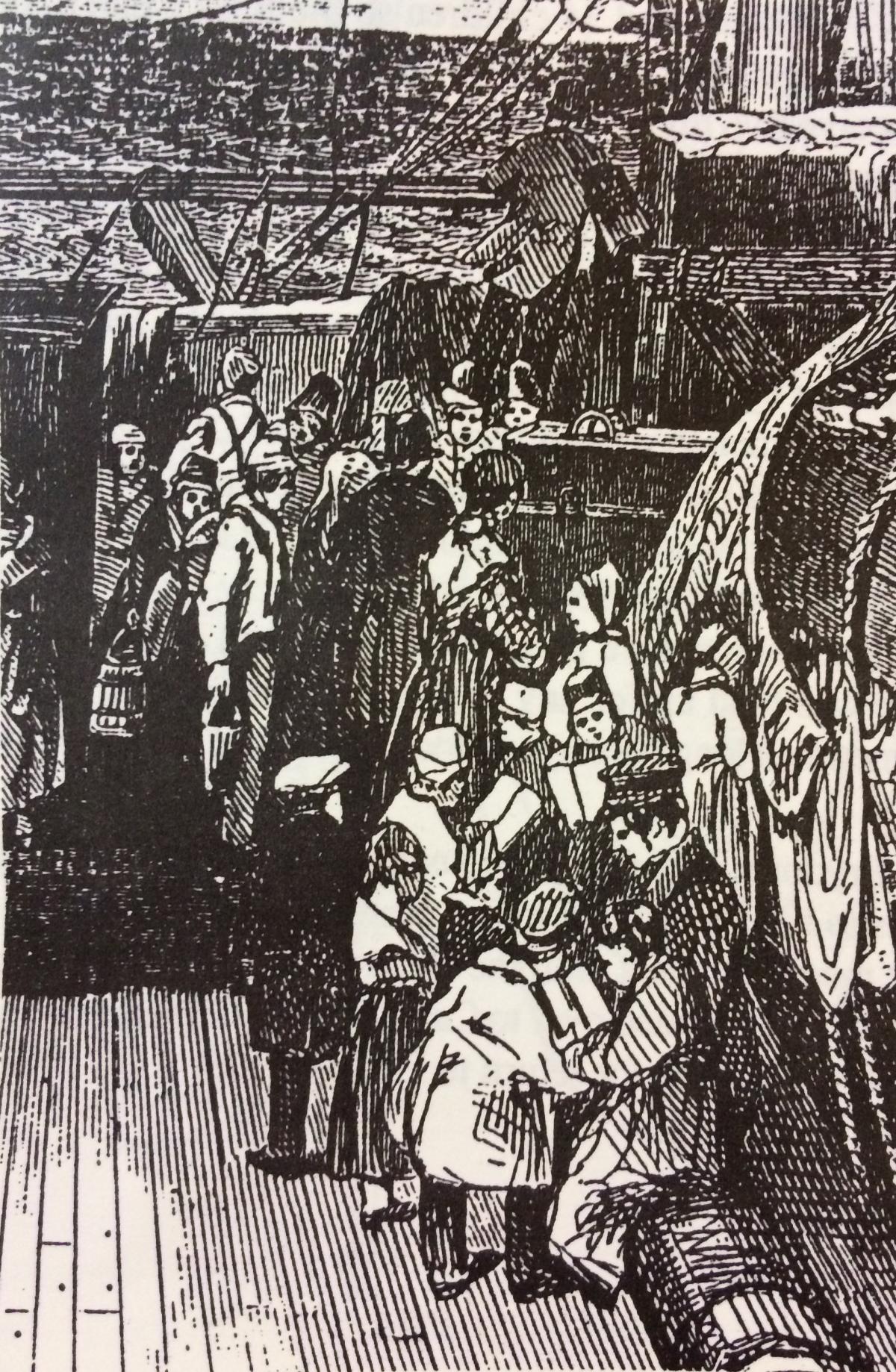

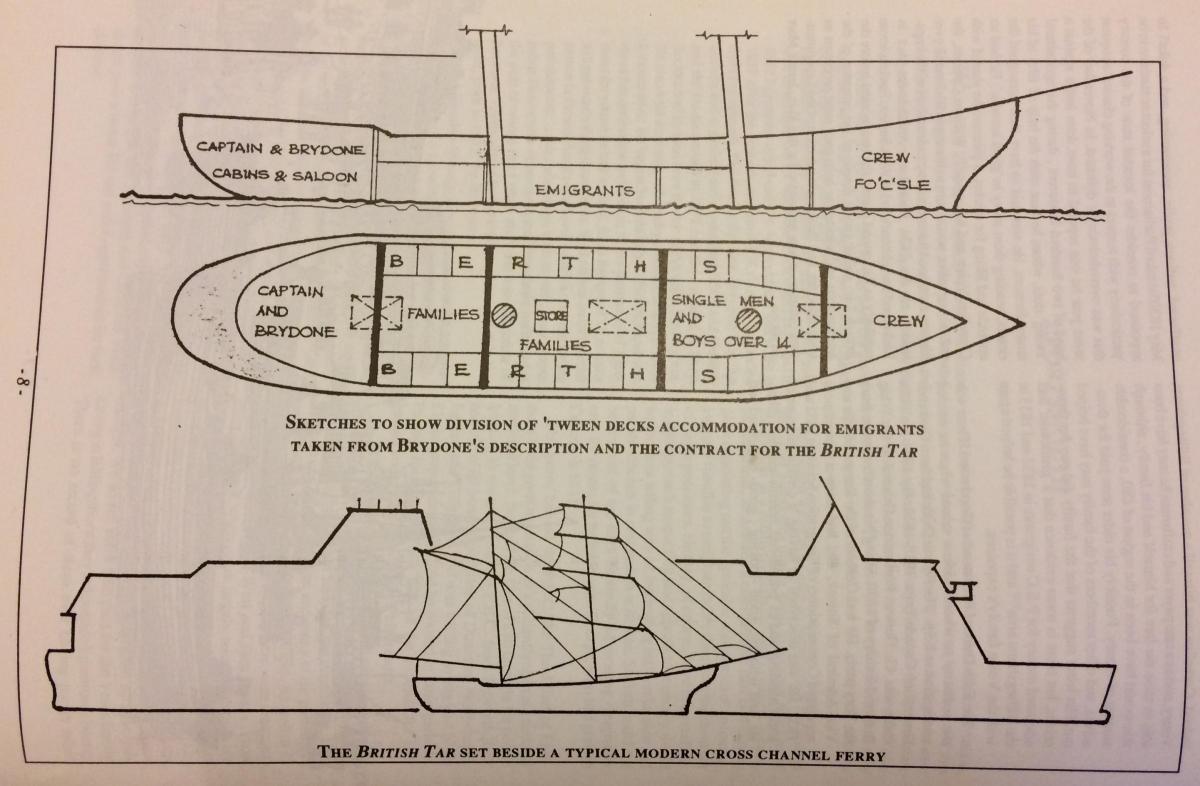

And long it was. Emigrants faced a seven-week voyage from Portsmouth to Montreal in cramped quarters with only two or three feet of headroom. Six square feet were allocated for every three adults or six children.

One Ms Ditton even had the unfortunate timing of giving birth on the voyage, though she was reportedly back to dancing on deck within weeks.

Upon landing in Canada, it took another three weeks by boat and wagon to reach their new home. But the lengthy journey was good for its time, says Petworth Emigration Project researcher Leigh Lawson

“They were checked to see if they were reasonably healthy before they were allowed on to the boat and food was adequate,” she said.

Not to mention the giant luggage list every emigrant was given.

“Necessaries” of 11 categories of items included pewter plates, “working tools of all descriptions” and a large watering pot. That exhaustive list did not cover the clothes or food required to make the trip.

Yet the necessaries were certainly necessary. Emigrants were given four parcels of unfarmed land and told to make do.

“The men from Sussex were used to working with wood but these were massive trees they had to clear,” said researcher Leigh.

Many died of cholera, a common cause of death mentioned in letters home. Housewives often found the experience isolating, stuck in remote homes and unable to meet friends.

But for many the new start was liberating.

Emigrants wrote home about catching rabbits and collecting firewood, something they were not allowed to do in England.

Just a year after making the voyage Ann, the emigrant from Wisborough Green, she said wanted for nothing. Writing home to family and friends, she urged them to come to Upper Canada as they would be “better off here than in old England”.

If they came, she would “make them as good a cup of tea as ever they drank in their life”.

To find out more about the Petworth Emigration Scheme visit the Petworth Emigration Project website at petworthemigrations.com.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here