RALPH Ellis did not talk much about his First World War experience, it seems.

His daughter Margaret’s biography of him does not mention his war time experiences at all.

But the longtime Arundel resident certainly did not forget his three years as a soldier.

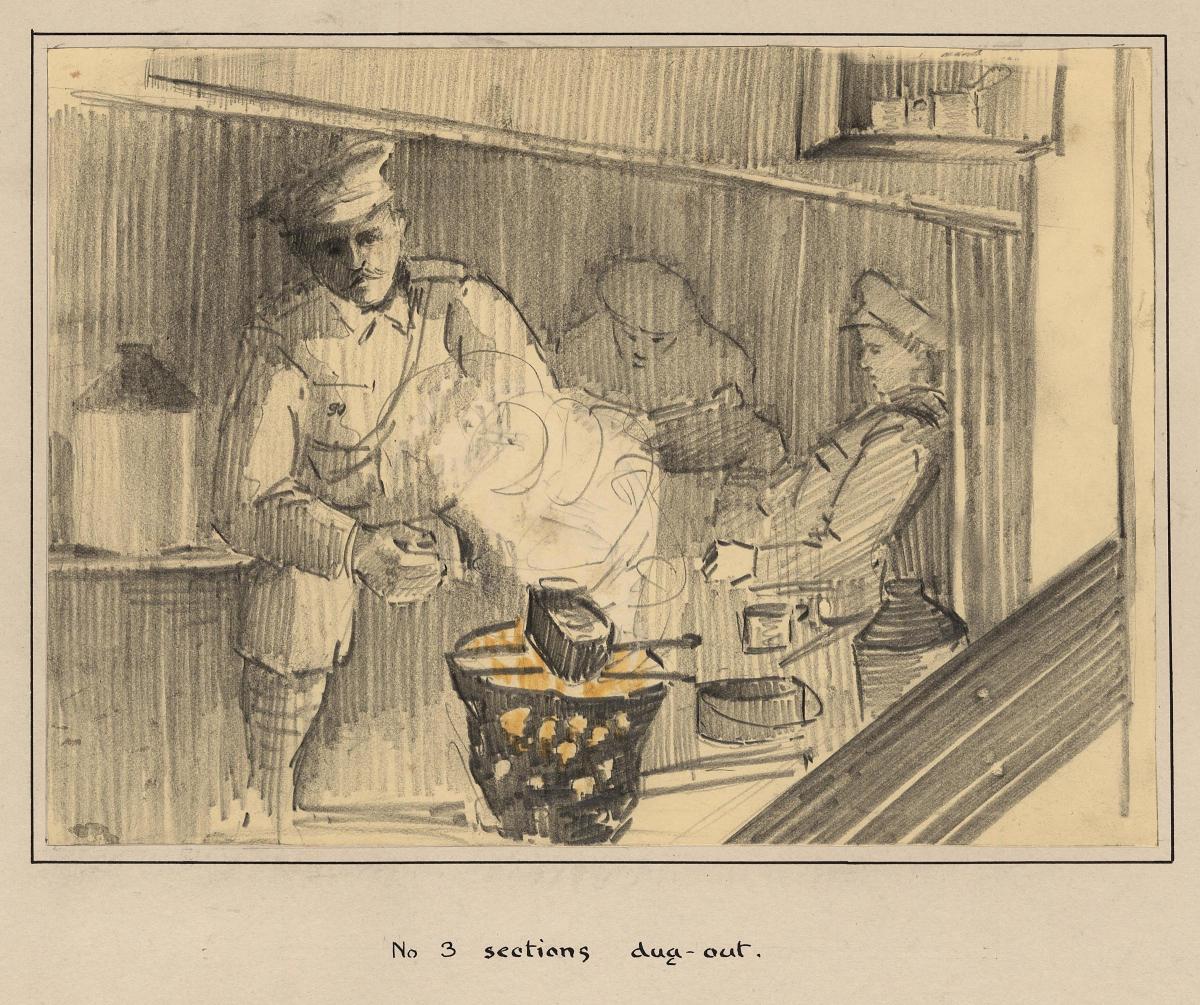

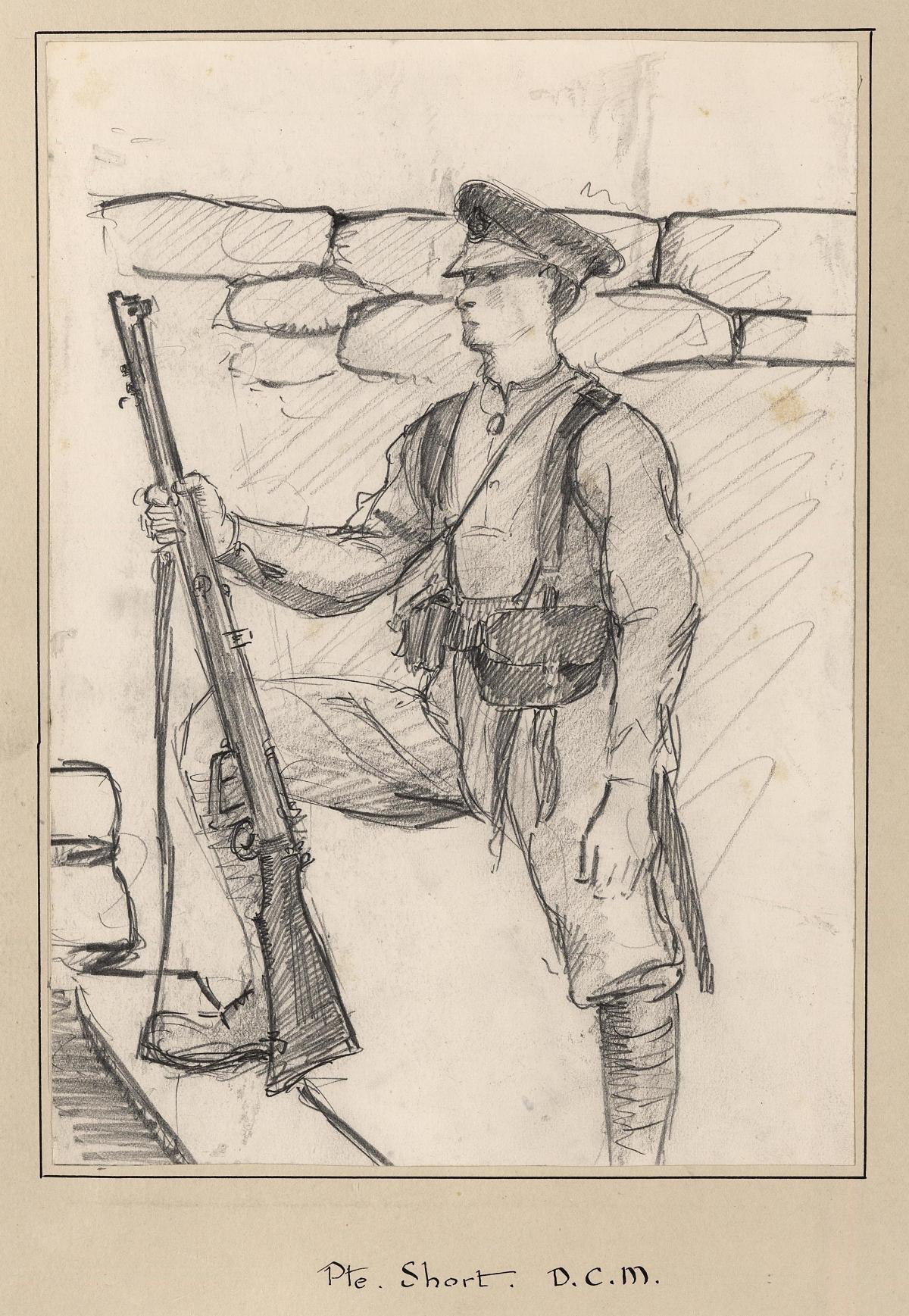

In his four years of recovery after being wounded in 1917, Ralph carefully compiled sketches and paintings he had created on the front line.

Soon he began adding words, describing the scenes where his pencil or paintbrush could not.

The ex-soldier ended up with five volumes describing his First World War years in colourful detail: the feeling, the smell, the taste.

More than a century after he first put quill to paper, the Sussex Record Society and West Sussex Record Office has published his memoirs.

Ralph’s book makes no grand statement about the war, nor does it give much historical detail.

Instead it conveys one ordinary man’s thoughts and feelings about the extraordinary environment he was experiencing.

“We pass on over the sheltering ridge and the road becomes a part of the other shelled ground,” Ralph wrote.

“Its surface churned into a thick mass, which tires the feet, fills the shell hole and partially covers the dead mules.

“The darkness hides much, but in such a place that intense nauseating smell, a combination of fumes from H. E. shells and rotting flesh, the odour of blood and iron.

“This is sufficient to direct one to the front.”

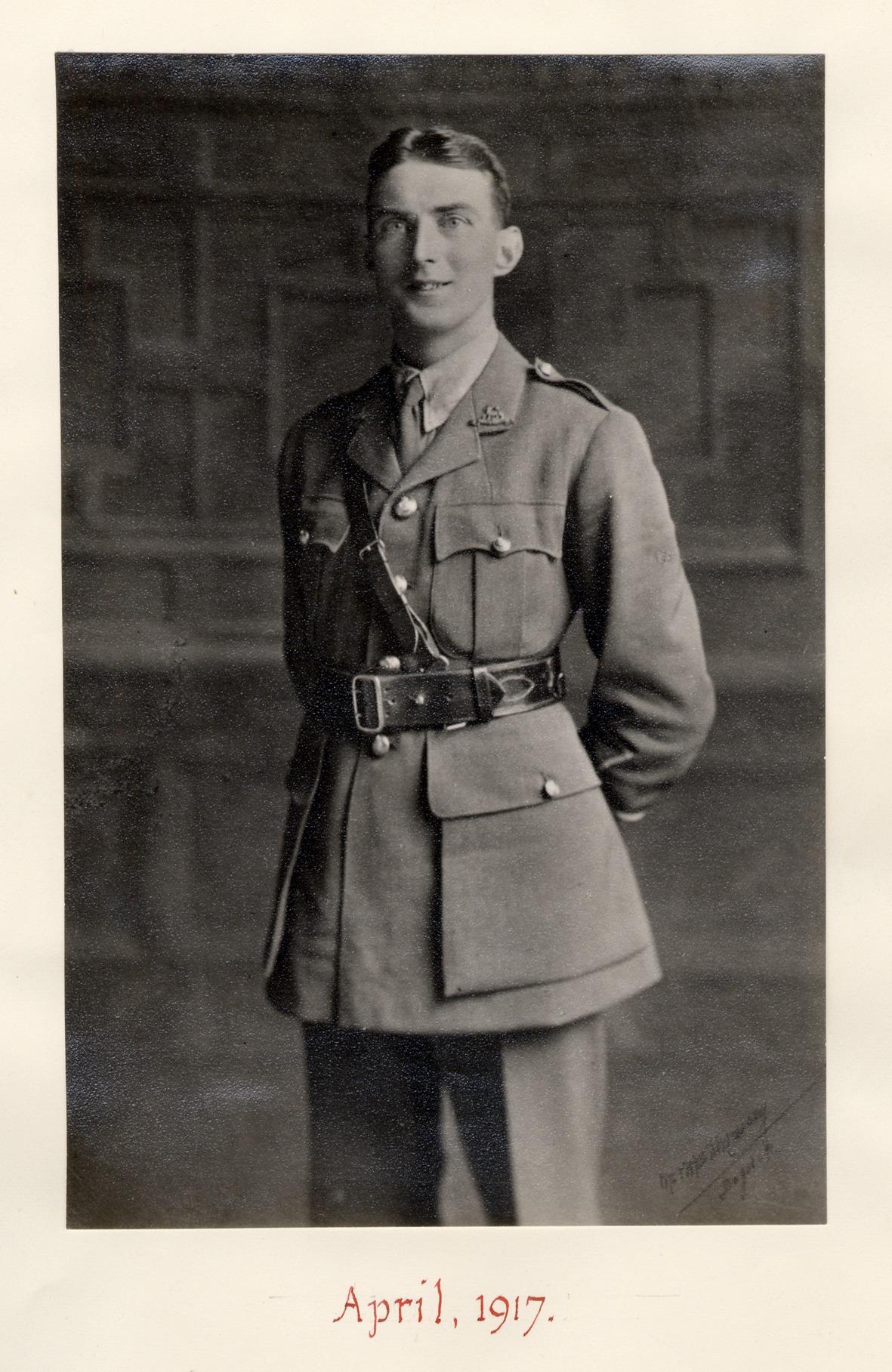

Born in Arundel in 1885, Ralph lived with his family above his father’s High Street shop.

In his teenage years he developed a passion for art, moving to London when he was 16.

But in 1910 he returned to Sussex and married Gertrude, setting up an art supplies shop in Bognor. He began to make a name for himself, painting portraits and landscapes of the countryside.

When war broke out in 1914, a 29-year-old Ralph was one of the first to sign up in Chichester.

Yet Ralph could not help but continue drawing while in training.

His comrades were a regular subject, as were his training camps.

The drawings continued when Ralph’s regiment was shipped to France in May 1915.

When he was away from the front he even began painting watercolours, lugging around a bag of paints.

His artwork soon began to focus on destroyed buildings.

One sketch, pictured top-left, was jokingly named “To Let”, a glimpse of gallows humour.

But Ralph was not a Siegfried Sassoon or Wilfred Owen. He was not trying to make a political point with his art.

Instead, editor Sue Hepburn says, drawing was simply second nature to him.

“It’s what he did,” she said.

“At one point he says ‘war is a waste’. He hated the damage it did to the landscape.

“[But] he never speaks against the war.”

Yet his sketches give a unique perspective.

Sticking your head above a trench parapet for a doodle was dicing with death. But Ralph often worked as a spotter for the artillery in observation towers. Many of his sketches depict not only the no man’s land but the land beyond.

The soldier first saw action in the Battle of Loos in 1915. The following year his battalion looked set to fight in the bloody Somme.

Yet for reasons unknown, Ralph was spared from the order. It probably saved his life.

Later that year he was promoted to an officer job and journeyed back to Britain to train.

He had barely met his new regiment when he returned to France in June 1917 when he was ordered to fight in the Third Battle of Ypres.

While inspecting a trench, he was shot in the left elbow and he was sent home. Ralph spent four long years in recovery compiling his memoirs.

Thankfully he was right-handed and remained an artist and sign painter in Arundel until his death in 1963.

Editor Sue suggests his memoirs were a way of working through his time as a soldier.

“It was cathartic,” she said.

“I think he couldn’t say enough with just a picture. He needed words to tell his story.”

The Great War Memoir of Ralph Ellis is available at sussexrecordsociety.org/shop.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here