Kemp Town has lost one of its very special residents. Mike Richey, seafarer extraordinaire, died just before Christmas, aged 92, at his home in Lewes Crescent.

He was an indefatigable solo yachtsman, an expert on astro-navigation, the founding director of the Royal Institute of Navigation and a stylish writer who imparted knowledge with clarity and elegance.

But these achievements, and others I will recount in a moment, are as nothing compared to his character. He was, to put it as its most simple and straightforward, a marvellous human being. And it was a privilege to know him.

His sister-in-law, Diana, summed him up best in an email to me, describing him as “wonderfully and infuriatingly eccentric, a total original” and adding: “In my view, his rarest achievement was to be 100 per cent his own man.”

I realised that fact on meeting him some time in 1971, soon after my wife and I first arrived in Brighton. He lived life at his own pace regardless of the pressures to do otherwise.

His little flat was in Lewes Crescent and his brother, Paul, lived three doors along from us on Arundel Terrace. Paul, a writer and air force war hero, and his wife, Diana, quickly became our friends, but they decided to leave early in 1973 and we immediately moved into their flat, where we still live today.

By then I had discovered something of the Richey brothers’ extraordinary life story. They were raised for a time in the court of Albania’s King Zog because their father, a former British army officer, was inspector general of the country’s police force. I can’t recall which of the boys claimed to be Albania’s first boy scout.

Many years after Zog’s fall, and death, Mike was still in touch with one of the Zogist princesses who, I seem to recall, lived out her years in Devon or Cornwall.

The core feature of Mike’s life was his Catholicism. He attended the Benedictine school at Downside Abbey, and had planned to become a monk. In many ways, living a solitary life on land and at sea, he could be said to have lived in a monastery of his own making.

In early life he was a pupil of the sculptor Eric Gill, the hugely influential sculptor, typeface designer and printmaker associated with the Arts and Crafts movement.

In 1939, aged 22, Mike joined the Royal Navy, and spent the war serving on a variety of ships. “This is where my taste for astro-navigation began, because there was nothing else to do,” he later wrote. “I took stars morning, noon and night for about a year.”

Such were his specialist skills as a navigator that they were put to use during the preparations for the D-day landings in Normandy. After the war he helped to found the Institute of Navigation (later, the Royal Institute) and directed its affairs for 35 years.

He later became president of the International Association of Institutes of Navigation, and an honorary member of several overseas institutes. In fact, though he never spoke of them, he was garlanded with awards.

He was the first winner of the Llewellyn Rhys Memorial Prize (in 1941) for his account of the mining of his minesweeper in the North Sea. In the United States, he was awarded the Superior Achievement in Navigation Award.

There were also many outstanding yachting victories, but Mike was best known for coming last in TransAtlantic yacht races because he revelled in the joys of the journey rather than reaching a destination in double-quick time.

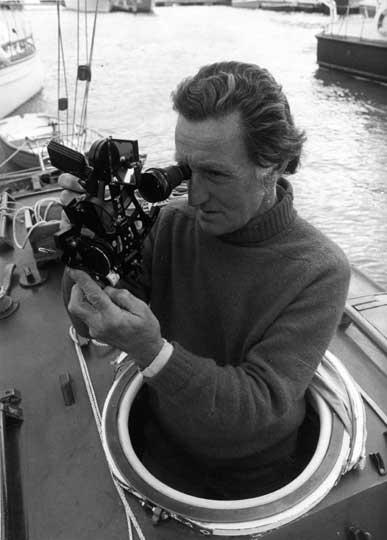

In 1965, encouraged by his friend Sir Francis Chichester, he bought a 25ft junk-rigged boat, Jester, that was to become the love of his life thereafter. It was also to figure in his major adventures during his 13 single-handed crossings of the Atlantic, on the last of which he celebrated his 80th birthday.

He was not only a master mariner but a master of understatement as his own account of a perilous 1986 voyage from Nova Scotia to England, Jester’s ultimate storm, illustrates. Some miles off the Lizard, in a violent storm, his beloved boat capsized. Though it righted itself it had taken on a great deal of water and he was obliged to cut the mast. He also suffered a bad back injury.

When it looked certain that he would sink he fired a flare that was seen first by a Spanish trawler. But he rejected their offer of help because it would mean abandoning Jester to the waves. Next came a British banana boat, Geestboy, captained by David Boon, and once again – despite the likelihood of sinking – he initially turned down help unless his boat could be saved.

An exasperated Boon, wondering about the mental state of a man refusing to leave a tiny dismasted sinking yacht, managed to reach Mike’s brother, Paul, by phone. His first question: was Mike armed?

Paul replied: “Of course not. But he’s dangerous if you try to part him from Jester.”

Boon, to his great credit, persuaded his crew to devise a makeshift cradle (supposedly from the banana hoists) so that man and boat could be hoisted to safety.

Mike wrote: “I was overwhelmed by the kindness of the captain and crew. It was a fine example of the brotherhood of the sea.” Paul and Diana drove to the South Wales port of Barry to welcome an injured Mike and his saviours. It had, as Diana recalls, been an astounding experience.

It was not until I went aboard Jester with my step-children, then moored at Brighton marina, that I realised the cramped conditions on the boat, which comprised a single cabin inside which the mast and rudder could be controlled. It seemed more like a submarine than a yacht.

It was a wonder that he was shipwrecked only twice and that he was not severely injured by the hatch cover that often struck his head.

The children adored Mike, who spent ages talking to them down their years. He was patient and kind towards them, as he was in his dealings with all the people who came and went from the area.

One of those who got to know Mike well was Diz Dymott, a cartoonist who lives on Chichester Terrace. From 1964 onwards he accompanied Mike to the start of every Atlantic crossing. He tells me: “Mike was more a romantic navigator in the mode of Joshua Slocum." Diz also points out that in the upstairs Greene room at The Cricketers pub, in Black Lion Street, there are copies of letters between Mike and his friend, the author Graham Greene.

Another of his friends, the writer and broadcaster Libby Purves, wrote a wonderful tribute to him in The Times, in which spoke of Mike’s “unobtrusive, unintended challenge to the way we live and think today.”

Diana Richey makes the same point. Here was a man who ate simply and lived simply. He did have a car, a battered deux chevaux, but used it sparingly, preferring to cycle everywhere. I spotted him less than six months ago pedalling away on the seafront. He did everything at his own speed. He was, quite definitely, a one-off.

Mike's funeral will be held at noon on Friday (22 January) at St. Mary Magdalen's Church in Upper North Street, Brighton, followed by a reception at the Old Ship Hotel.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here