As he prepared to write The Grapes Of Wrath, John Steinbeck wrote, “I want to put a tag of shame on the greedy b******* who are responsible for this.”

He was referring to The Great Depression and the banks which foreclosed on mortgages and let smallholdings in Oklahoma go under.

The author directed his anger at organisations colluding with corporate farmers to drive down prices to force tenant farmers out of business.

On the 75th anniversary of its publication, Maggie Gee, novelist and professor of creative writing at Bath Spa University, told the BBC that Steinbeck shows “when there is a great separation between those who look after the money – the banks – and those who need the money – those who produce and those who work – things go horribly badly wrong.”

She added, speaking on the Radio 4 programme Start The Week, that we should remember “we are all capable of greed but it is the banking profession whose job it is to look at itself and be responsible.”

Yesterday RBS, the 81% taxpayer-owned bank, announced its biggest yearly loss, £8.2bn, since it was rescued by the UK government but still set £576m aside for staff bonuses.

Earlier this week, HSBC handed its CEO Stuart Gulliver “fixed pay allowances” worth £32,000 a week on top of his £1.2m salary. The rebranding is to side-step restrictions on bonuses imposed by the European Union.

The TUC accused HSBC of “soar-away boardroom greed”.

Barclays, another bank with UK high street operations, has increased its bonuses for top bankers by 10%, even though its profits fell 32%.

The EU has tried to cap payouts (George Osborne is currently taking legal action against the EU), but five years after the worst economic crash in living memory, has anything really changed in banking practices?

Paul Moore, the man who lost his job at HBOS after sticking his head above the parapet to speak out about excessive risk-taking, told The Argus he thinks not.

“If you asked 100 ordinary people if they think banks can be trusted, I would be absolutely astonished if five of them said they trusted a bank.

“You only need to look back a couple of months to see Lloyds Bank was fined a further £28 million for setting up incentive schemes which encouraged mis-selling, and that was designed post crisis.

“You have Paul Flowers, who was appointed chairman of the Co-op Bank, who was called the ‘crystal Methodist’, and every other day we get something else happening.

“Barclays is increasing bonuses again – and by the way, that’s increasing bonuses on top of increased basic salaries.

“So banks really haven’t reformed themselves. There are a lot of fancy words about changing the culture and all the rest of it. But frankly we haven’t really solved the problem of greedy bankers yet.”

Sharing the power

We are chatting before Moore visits Brighton for a day of debates and polemics about fairness as part of Brighton Science Festival.

Moore advised the Parliamentary Commission on Banking Standards for its report, An Accident Waiting To Happen: The Failure Of HBOS. Andrew Tyrie, who has the following thoughts on the EU’s proposal for a bonus cap, chaired that commission.

“A crude bonus cap does nothing to incentivise higher standards. What we need is a fundamental reform of the bonus culture including much longer deferral and much greater scope for clawback, as the banking commission proposed.”

Moore agrees with fundamental reform. He adds, “It is not terribly complicated to run a bank, so why should the chief executive get paid £10miilion?”

When Adam Smith wrote The Wealth Of Nations, the bible of free market economics, there was an idea of a consciousness which acted as an invisible restraint on companies and their behaviour. What we have now are companies with balance sheets bigger than sovereign governments and more power than most of them.

“If you allow the executive to have unbridled power, and the non-executive and the risk functions can’t slow it down, you will end up with a situation when the love of money and profit takes over from fairness and integrity and all the other things society wants.”

Which leads to a situation where banks can use depositors’ money, with the leverage that gives them, to speculate on all manner of different financial instruments.

“Banking is a business about providing credit – and in merchant banking sometimes equity – to businesses and households and families and individuals to do things with on a prudent and sensible basis.

“There are inherent systematic problems in the banking system. It boils down to this: they have promised their shareholders rates of return which they cannot deliver to shareholders unless they treat their customers unfairly.”

Back in 2004, Moore tried to warn HBOS’s board that disaster would follow if it continued its excessive risk-taking. “I suggested if they carried on that way they were going to blow the bank up.”

There was an inadequate separation and balance of power between the executive and everybody else who was trying to keep them in order.

“The executives could do what they liked and no one would stop them, including regulators and auditors. And you can have the best government processes in the world but if they are carried out in a culture of greed, unethical behaviour and indisposition to challenge, they will fail.”

Martin Scorcese’s The Wolf Of Wall Street and Charles Ferguson’s The Inside Job make for entertaining background viewing.

Moore appeared on Newsnight the night his former boss James Crosby – “the prominent incompetent” according to Jeremy Paxman – announced he was going to hand back his knighthood. It happened to be the day Maggie Thatcher died.

“Some sceptics say he did that in order to bury the news but it didn’t happen.”

Moore describes being a whistleblower as like having the plague. Edward Snowden would surely agree.

“You had a culture where if anybody spoke up they got shot. And that is what happened to me.”

Lloyds, which acquired HBOS in 2009, has shed 38,000 staff since the crisis. On a wider scale, the banking crisis drove 100 million people around the world back into abject poverty, reports the UN.

As for Moore, he had not been offered a single professional role until December 2012 when he joined peer-to-peer lender Assetz Capital which launched last March.

“Once you have been a whistleblower you are excluded from the profession even by those on your side; they don’t want to come too close in case they get infected by you and your toxicity.”

Assetz Capital removes banks from the lending equation using the internet in a similar manner to crowd-funding sites. It connects investors with borrowers and “democratises things”.

“If it is run by a scoundrel it won’t be ethical. It is all down to who is running it. We are ethical, and we do our jobs properly.”

Moore does not believe companies such as Assetz, Zopa and Funding Circle will take over the world of banking but sees substantial growth.

“This is a way of getting involved in something that could make a difference in a positive way. I describe it as positively disruptive finance replacing what has been positively disgusting finance.”

A recent article in the FT highlighted how directors of car manufacturers have increased pay by 19% since 2009 while all the workers are earning 7% less.

The level of inequality in the US between top and bottom is greater now than it was in The Great Depression, when Steinbeck saw the banks as the opposite of socially useful.

Shockingly, 95% of all income gains in America since 2009 have gone to the top 1%. And 90% of the poorest people are earning less than they did then.

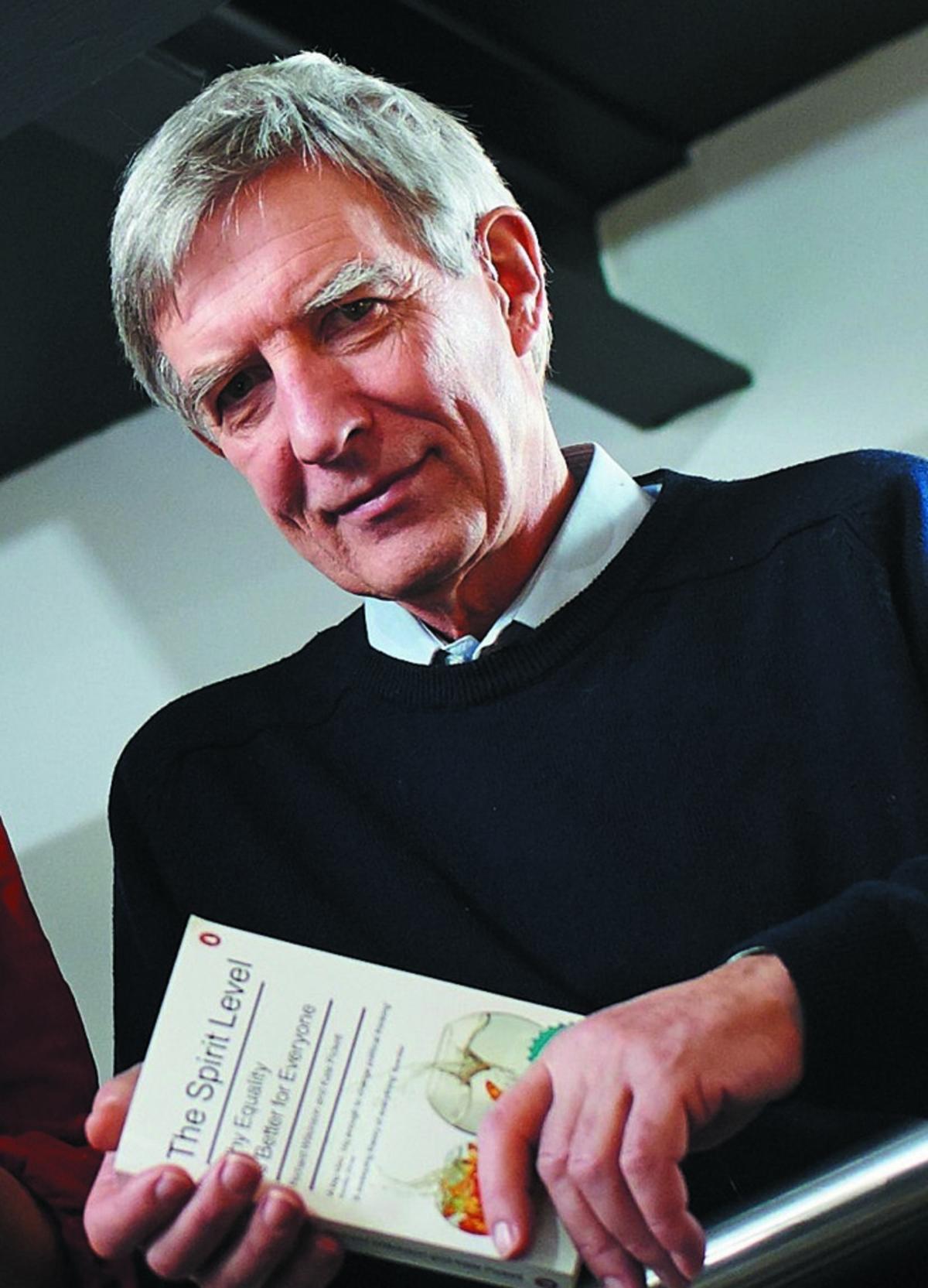

For epidemiologist Richard Wilkinson, another speaker at Brighton Science Festival’s All The Fair Of The Unfair, inequality has disastrous consequences.

“Problems we know are related to social status, the things that get worse at the bottom of the social ladder, also get worse if you increase status differences.

“The whole of society suffers – even middle classes do worse in more unequal societies.”

Wilkinson is co-author with Katie Pickett of influential equality treatise, The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better. He is a former senior research fellow at the University of Sussex’s Trafford Centre for Medical Research.

He cites 11 different health and social problems – including physical and mental illness, life expectancy, violence, child wellbeing and social mobility – as significantly worse in more unequal rich countries.

“It is clear there is a direct correlation. We show how a country’s proportion of population in prison, for example, is related to inequality in each country. “You can see very easily the more unequal countries have more people in prison.”

The Spirit Level argues there are “pernicious effects that inequality has on societies: eroding trust, increasing anxiety and illness, encouraging excessive consumption”.

He believes economic growth has transformed lives but “largely finished its work”. He disagrees with the ideology that further economic growth will benefit everyone and trickle down to the poor.

“If you look at rises in GNP per capita in the rich world, it no longer improves happiness or wellbeing.”

That’s to say, now we are rich the battle is for status. But we can’t all improve status in relation to one another. We need to concentrate on better sharing of the wealth we have.

“Status itself becomes more important in a more unequal society. There is more status competition with greater inequality. It’s as if your worth is a matter of where you fit in. And we see money as an indication of personal worth.”

David Cameron name-checked The Spirit Level a few months before being elected in 2010.

“Research by Richard Wilkinson and Katie Pickett has shown that among the richest countries it’s the more unequal ones that do worst according to almost every quality of life indicator.”

Ed Miliband cited the theory, too, “The gap between rich and poor does matter,” he said. “And it doesn’t just harm the poor, it harms all of us.”

Wilkinson, speaking from the organisation he founded in York, The Equality Trust, explains inequality is not the only cause but is a common cause of social problems.

“Inequality has come on the political agenda since the book was published and since the financial crash. The concern with poverty and bankers’ bonuses is about inequality and unfairness. This sort or research has to eventually influence public opinion.”

It comes back to economics. We might think there are inequalities in power and status but inequalities of power are about access to resources.

“The pecking order is about gaining privileged access to scarce resources and status is simply recognition of power and wealth.”

Redressing the balance

The gap in rich countries is widest in the US, followed a close second by the UK. Scandinavian countries, Germany and Japan have smaller income difference thanks to taxes, benefits, better corporate structure and employer (producer) cooperatives.

UK inequality was at its lowest post-war with the New Deal, the NHS and welfare state. It began to dive in the 1970s.

“There is no doubt the modern increase in inequality is a reflection of the neo-liberal economics of Reagan and Thatcher who pioneered it.

“You can also tie it to first the strengthening and then the weakening of the whole labour movement.

“To keep income differences low you need a counter voice in society, which the labour movement was.”

The bonus culture is an indication of a lack of any democratic constraint on people at the top, adds Wilkinson.

The Spirit Level has not been without its critics. Sussex-based professor of sociology Peter Saunders criticised the data in a report for think tank Policy Exchange.

But Wilkinson stresses he is an epidemiologist – the study of the patterns, causes, and effects of health and disease – and much criticism has come from different fields. Not only that, to produce a readable account they did not include many technicalities, which the British Medical Journal has since published.

Concentrate on making the gap between incomes smaller rather than pursue economic growth, he says.

“If you think of the FTSE 100 companies, the average pay difference between the CEO and most junior full-time workers is about 300 to one.

“And there is no more powerful way than telling a great swathe of the population that they are almost worthless than to pay them one third of 1% of what the CEO in the same company gets.”

- All The Fun Of The Unfair, Brighton Science Festival, Sallis Benney Theatre, Grand Parade, Brighton, Sunday, March 2

-

12.30pm to 6pm, £10/£15. Visit www.event

brite.co.uk/e/all-the-fun-of-the-unfair-tickets

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here