Someone Who’ll Watch Over Me

Minerva Theatre, Oaklands Park, Chichester, Thursday, September 10, to Saturday, October 10

“ONE of the most depressing experiences in theatre is rehearsing a comedy. After about five days the cast don’t find it funny, and there’s nothing to bounce off.

“In a bleak situation you develop a wonderful black humour which carries you through.”

Inspired by the hostage crisis in Beirut, Frank McGuinness’s Someone Who’ll Watch Over Me is the story of three prisoners, who spend most of their time chained to the floor by their unseen captors.

But making his Chichester debut director Michael Attenborough is enjoying the experience of what he admits is an intense and exhausting play, but shot through with wonderful passages of humour, imagination and flights of fancy.

It’s his fourth collaboration with his close friend, writer McGuinness, having first worked with him at the Hampstead Theatre in 1986 on his breakthrough play Observe The Sons Of Ulster Marching Towards The Somme.

“It’s one of the great plays of the later 20th century,” says Attenborough, who in 2013 quit as artistic director of London’s Almeida Theatre after 12 years at the helm to focus on life as a freelance director.

“I’ve always wanted to do it, but because it had been done before I didn’t expect it would come along.”

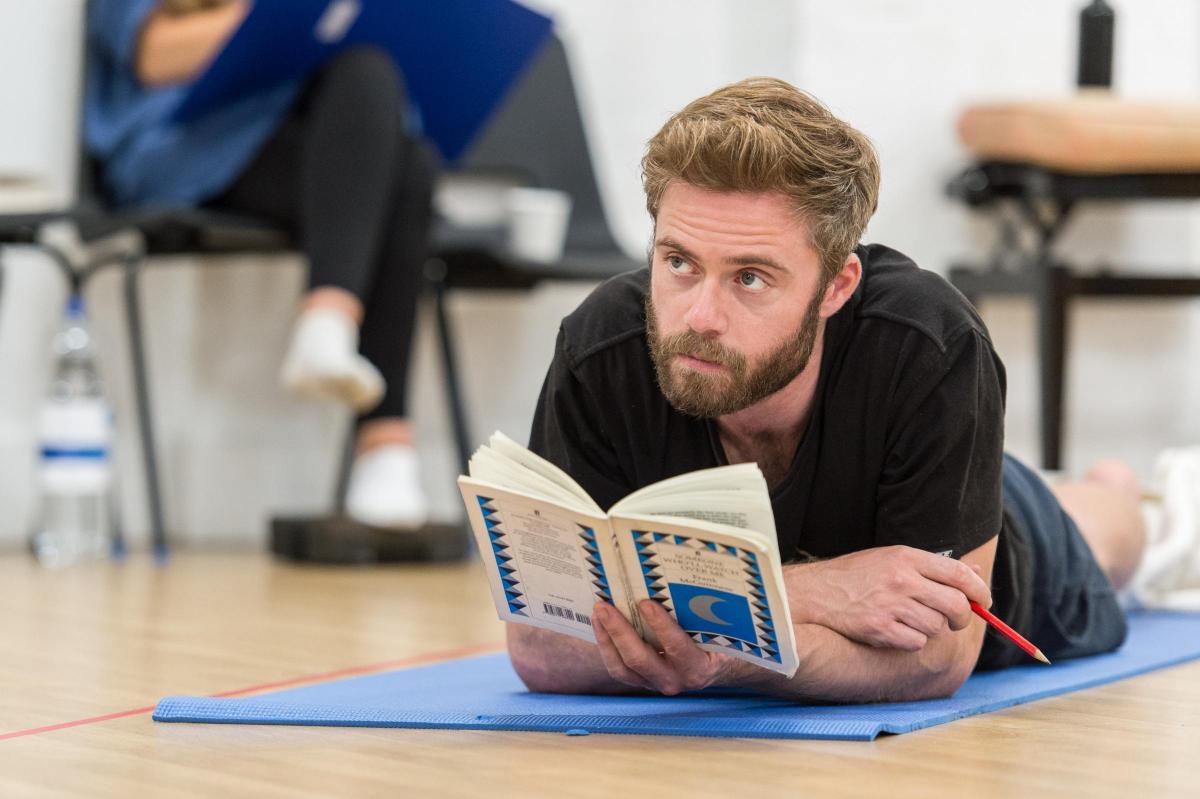

Joining him in the rehearsal room are David Haig as English academic Michael, Rory Keenan as Irish journalist Edward and Adam Rayner as the American doctor Adam. For both Keenan and Rayner this will be their Chichester debut.

“The rehearsal is happening on two levels,” says Attenborough, son of the late cinema director and producer Lord Attenborough who died last year.

“I’m creating an atmosphere in which people can feel secure and enjoy themselves, leave their ego at the door. They are three people who didn’t know each other before – but they have spent the last four weeks in each other’s pockets working creatively. We have two sets of relationships – the personal relationships of the actors and the characters themselves.”

The story itself was penned in 1992, following the release of academic Brian Keenan and journalist John McCarthy, who were captured by the Islamic Jihad Organisation in 1986 in Lebanon and held hostage for more than four years.

Attenborough read both former hostage’s autobiographies as preparation for the play, but is keen to point out McGuinness’s play is about very different characters.

“The Irishman in the play is more cynical and can be quite cruel,” he says. “Edward worked hard and played hard, and was distant from his family, although in the play misses them and realises when they are not there how much he values them.

“Keenan was a complicated, extraordinary family man.”

He does point to a similarity in the way both the character of Edward and Keenan approach their situation.

“Brian told John McCarthy one of the ways they were going to survive was by helping take each other to breaking point,” he says. “If they could stay resilient with each other, they would stay resilient with anybody they encountered. Edward does that in the play.”

Rather than consider questions of Islam, or the motivations of their unseen captors, the play is about how the three men survive, and plays on their different nationalities.

“If your family, your clothes, your possessions and everything that makes you who you are taken away from you, the only thing they can’t take away from you is your nationality,” says Attenborough.

“It becomes a form of identity for the three characters, something they can cling to, but it almost becomes an Achilles heel for them. They play into stereotypes and take the p*** out of each other. What is written into the play is the assumptions the characters make about each other.”

What has changed in the post 9/11 world is the experiences of hostages in the Middle East – especially with the rise of IS and the infamous Jihadi John.

And the fear of execution is in the background of the play throughout.

“The characters don’t know whether they will see out tomorrow,” says Attenborough. “They are living on the edge all the time. Questions about whether they will go home or stay alive are going around their heads.

“In the 1990s Keenan was let out first and spent an awful year waiting for McCarthy to be released. He says he was in hell without his friend. When John was freed it changed Keenan’s life.”

Attenborough is particularly looking forward to the intimacy of Chichester’s Minerva thrust stage.

“With a space like the Minerva you don’t have to shout all the time,” he says. “It’s a tricky play in that it’s about three people chained to the floor – it doesn’t have a lot of movement. The characters face each other, so some of the audience will have the actor’s back to them. But where the intimacy becomes a fantastic help is that although they can’t see the actor’s face they can feel what they’re going through, reading it off the way they speak and move.”

Starts 7.45pm, 2.45pm matinees, tickets from £20. Call 01243 781312 or visit cft.org.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here