ONE hundred years ago today the allied forces landed at Gallipoli, marking the beginning of a bloody campaign that would cost thousands of lives. Such was the devastation of the Anzac troops, Australians and New Zealanders rank the anniversary above that of Armistice Day. But unknown to many, the Royal Sussex Regiment also played a key role in the First World War campaign. ADRIAN IMMS reports on the special anniversary

Sometimes the enemy is not just the man across the field with a rifle aimed at your head. Sometimes it’s also the stifling heat, the onset of disease, tough terrain and a lack of food or water.

No more so was this obvious than during the First World War – the first real conflict that brought the various horrors of battle home to people.

While this four-year hell is best known for the bitter cold, trench foot and mustard gas of Europe’s Western Front, it also comprised an ill-judged campaign fought in the sun of what is now northern Turkey.

Soldiers, including men and boys of the Royal Sussex Regiment, landed on beaches with a mission to capture Gallipoli.

But a slow advance and mixed messages meant the Turks had time to organise themselves and occupy the high ground.

Gun fire swept along the lines of advancing Allies as artillery shells burst around them, setting the scrub on fire.

Enemy snipers, who knew the hills well, were devastating and hard to find – the campaign descended into trench warfare over a disastrous eight-month period.

All of these things, combined with illness, conspired to paralyse initiative.

When troops were able to fight their way forward, they were tired and spread thin. The chaos and confusion of orders and counter orders, with few maps, reduced morale even more.

It had been thought that the best way to break the deadlock of European trench warfare in 1915 was a series of beach assaults on the Gallipoli peninsular, a rugged outcrop of the Ottoman empire near the border of Greece and Bulgaria.

A narrow strait of sea cut through the area, providing trade access to Constantinople (now Istanbul) and, ultimately, Russia from the Mediterranean and Aegean Sea.

By capturing Constantinople, the British hoped to link up with Russians, knock Turkey out of the war and persuade the Balkan states to join them.

But where the Normandy invasion was meticulously planned, the Gallipoli campaign only came together in the early weeks of 1915.

The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (Anzac), about 30,000 strong, was tasked with landing in what has become known as Anzac Cove, while 28,000 British tried for Cape Helles. About 17,000 French also made a diversionary landing.

It was ill-fated from the start. A Naval bombardment campaign went wrong in February 1915 because of bad weather, and ships went down. When the Allies did manage to land on April 25, the Turks had fortified their positions and defending forces were six times larger than when the campaign began.

In July, the British reinforced troops and so the fighting and carnage continued.

It was not until August 8 that the 4th Battalion of the Royal Sussex Regiment, having left Britain on July 16, became involved, landing further north at Suvla Bay and advancing in-land to Salt Lake, where they first came under fire.

In all, there were about 50,000 troops when 80,000 were needed. They were facing up to 75,000 Turks, with reinforcements arriving every day.

The plan was to quickly capture the high ground – speed was of the essence. Each man was issued with 100 rounds of extra ammunition and moved up to surprise Turkish troops, but the going was tough. The next day the Royal Sussex was 750 strong, although a war diary put the battalion at 250 despite only recording a total of 12 killed and 63 injured.

Colonel Roderick Arnold, president of the Royal Sussex Regiment Association, said: “Such must have been the chaos that the true figures were impossible to know.”

Throughout September, the Allies spent time reinforcing trenches with barbed wire and then building winter accommodation.

They continued warfare training but preparations would be in vain and, as costly Turkish counter-attacks continued, plans to evacuate began. By mid-December, the Allies were heading to port to leave. Royal Sussex troops were ordered to evacuate on December 13 and left two days later. The regiment had arrived with about 750 men and left with 231 troops.

Casualty figures for the whole campaign vary, but it is believed that more than 56,000 Turks died with 53,000 British and French soldiers and about 8,700 Australians. The number of casualties on all sides including injured, sick and missing was nearly 500,000.

Seen as a great Ottoman victory and a major Allied failure, it was a defining moment in Turkey’s history. The struggle formed the basis for the Turkish War of Independence and the founding of the Republic of Turkey eight years later.

From the Allied perspective, there was too much deliberating among generals over small detail. Further up the chain, another man blamed for the mess was Winston Churchill. As first lord of the admiralty, he was seen as the father of the attack.

Despite this, he went on to become prime minister during the Second World War and banished his Gallipoli demons when he struck Hitler’s “soft underbelly” with beach landings in Italy that successfully unlocked Europe and paved the way for D-Day.

Historian Peter Hart is set to share his knowledge of the Gallipoli campaign in Major Bromley’s home town of Seaford. The Redoubt Fortress hosts the talk on May 9 as part of a military history series. Mr Hart will draw on personal accounts of those who lived and experienced the Gallipoli campaign. It starts at 2pm in Casemate 20, a room in the fortress, with refreshments in the Outpost café. Tickets are £12. For more information, visit eastbournemuseums.

co.uk or call 01323 410300.

Lives lost in Gallipoli conflict

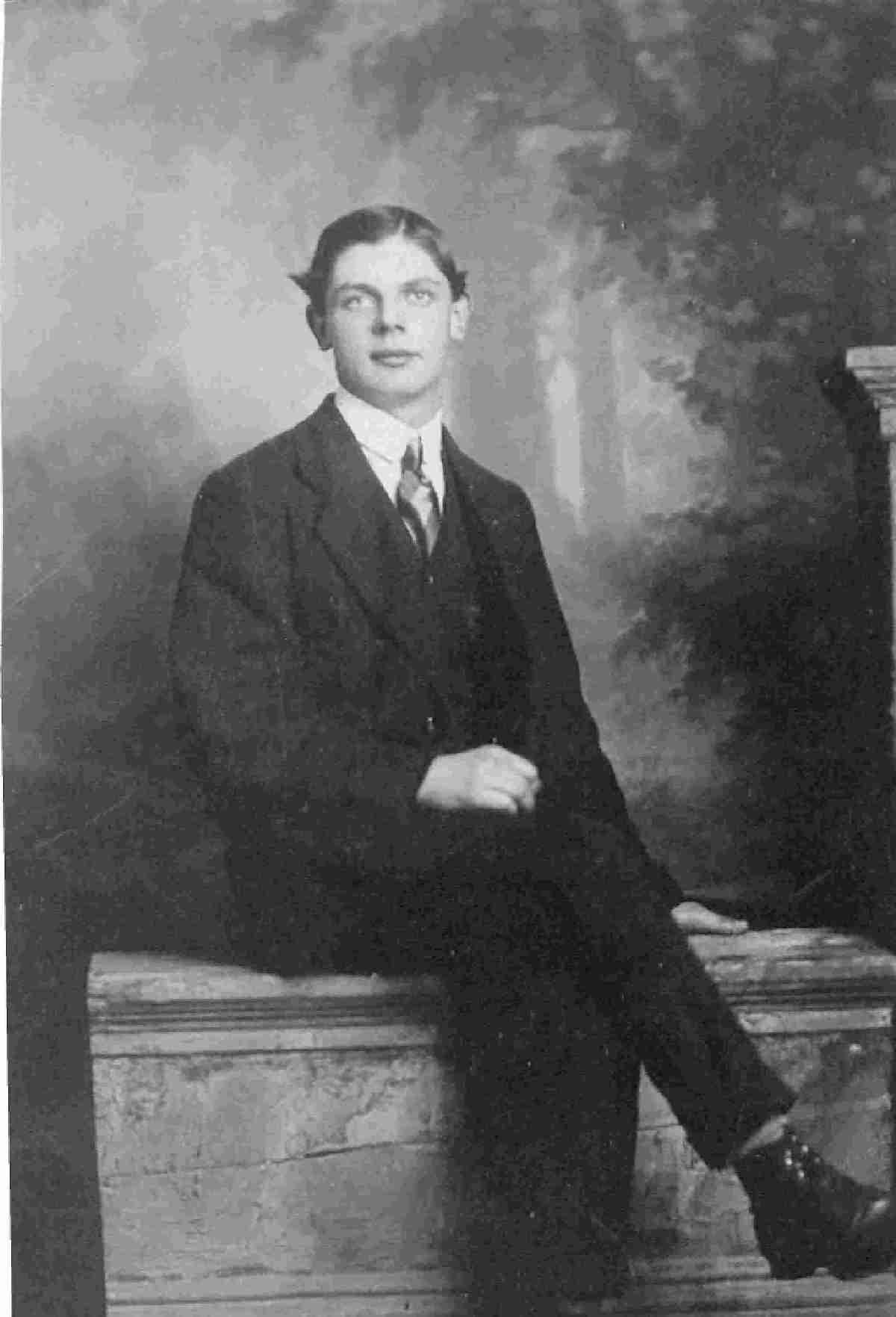

Many men from Sussex lost their lives in Gallipoli. Among them was private Herbert Charles Paice, pictured below, who died on November 14, aged 20, while the Allies were trying to push forward.

Serving with the Royal Sussex Regiment, he had grown up in the village of Paige near East Grinstead.

His death was reported in the East Grinstead Observer on November 27, 1915.

It reported that “he was very well known and respected in the locality”, adding that “much sadness is being expressed to Mr and Mrs Paice in their sad bereavement”.

Following Gallipoli, he was buried in the Cairo War Memorial Cemetery in Egypt.

Pte Paice is the great uncle of Peter Atkinson, 58, of Portslade, who visited his grave in Cairo two years ago.

Mr Atkinson said: “Herbert was my gran’s favourite brother but she never got a chance to visit Gallipoli or his grave in Cairo.

“Laying a small cross and poppy at the site where many of the Royal Sussex Regiment are buried was very moving.”

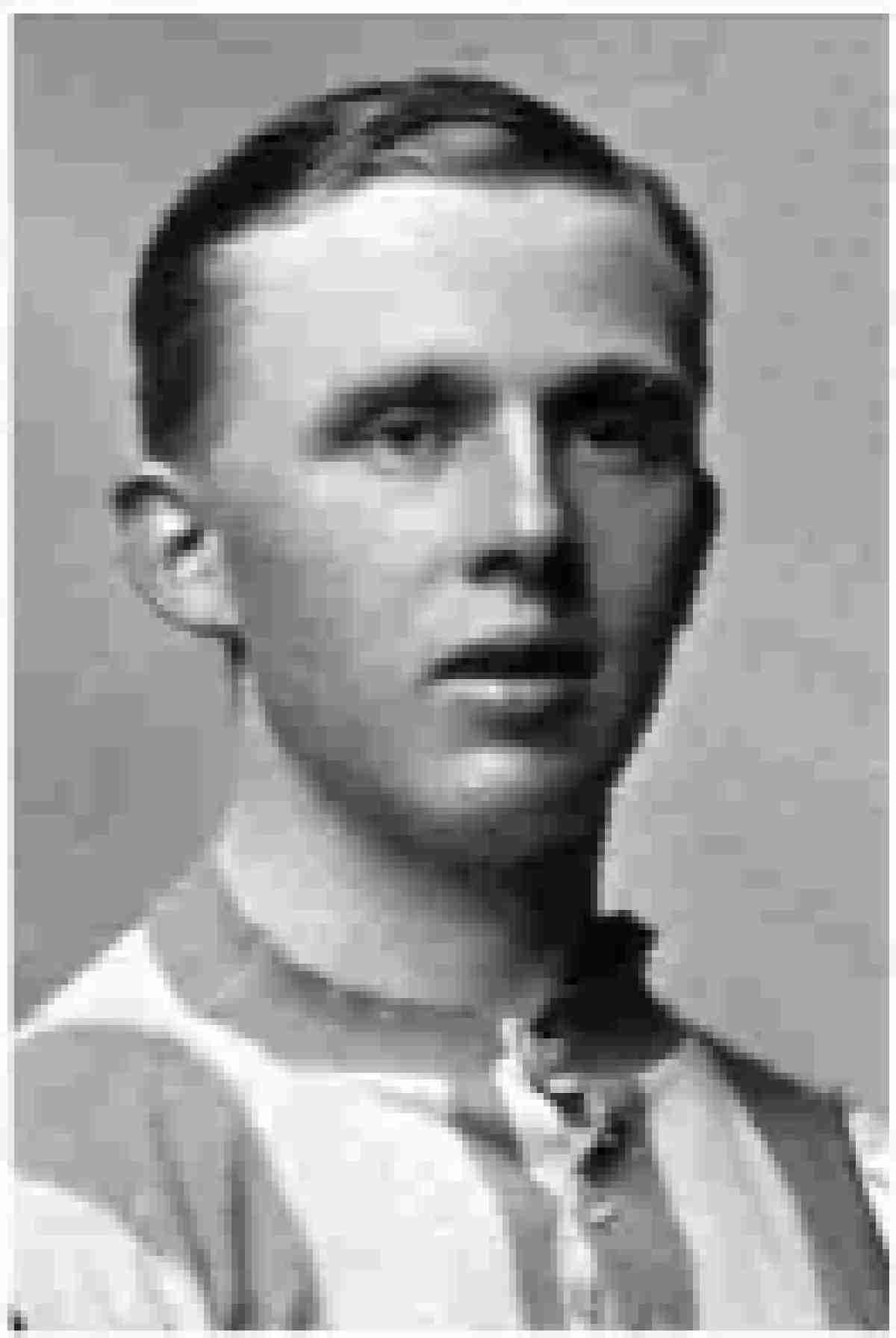

Another victim was private Clement H Matthews of the Royal Sussex. He was killed in action on August 15, aged 26.

After landing at Suvla Bay he was shot dead by a Turkish sniper.

Known as Charlie, he was born in Falmer, where his father was working on a local farm.

He was initially a bricklayer in Horsham before becoming a footballer for Brighton and Hove Albion.

Although mainly a reserve player, he made 12 appearances for the first team.

Another soldier who died is a distant relation of Brian Varty, 59, who lives in Hurstpierpoint.

Mr Varty does not even know the soldier’s first name – he was listed only as Private Varty in a commemorative edition of the Sydney Morning Herald in the early 1990s.

Private Varty was only 19 when he was killed on the first day of the landings on April 25.

Mr Varty said: “He went to Australia when he was 16. We think he was my paternal grandfather’s brother or cousin. The Australian side of my family only have vague memories.”

Mr Varty added that the conflict was thought to be the first time Aussie and Kiwi forces fought separately from the British.

Higher up the chain was major Cuthbert Bromley, from Seaford, an adjutant to the commanding officer at Gallipoli. Aged 36, he was wounded in the back but refused to leave his men, only reporting it three days later when he was shot in the knee.

He was badly wounded in the foot two months later but refused to leave his post until the battle was won.

After being treated in Egypt, he was killed when a troopship taking him back to Gallipoli was torpedoed and sunk. He was seen helping people before he was hit on the head with driftwood and drowned. The Victoria Cross that he won is one of six to go on show at the Fusilier Museum in Bury, near Manchester.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel